A large, darkened room with 132 Tiffany

lamps on display, each having its own space, each illuminated and casting a

soft glow. Reddish or brown bronze bases

topped by polychrome shades of glass, mosaics of small pieces of luminous red,

yellow, blue, green, purple, and pink: miracles of glass, of color, of

light. Looking closely at one lamp, one

sees a ring of dragonflies with red bodies, their yellow wings extended

horizontally, and above them on the shade, a band of green and blue that could

be the water they are darting over, and at the very top of the shade, a patch

of blue that might be sky. Another lamp

suggests purple wisteria drooping languorously, and another, the wings of a

peacock with eyespots of red and green. Other shades are geometrical, with triangles

and squares and ovals of many colors, still others show daffodils or peonies or

poppies, or spiders with webs, or butterflies: nature enhanced, transformed. This room is magic; to leave it is jolting,

dispiriting, sad.

|

| Cliff |

The room just described exists only in my

imagination, but it or something like it will exist on the fourth floor of the

New York Historical Society in 2017, when their new installation is completed

and opens to the public. In the meantime

I have to settle for whatever my imagination can cook up.

|

| A wisteria lamp. Fopseh |

|

| A dragonfly lamp, plus pigeons. Rickjpelleg |

“Tiffany”: the name suggests luxury,

quality, style. There are no Tiffany

lamps in the West Village apartment shared by me and my partner Bob, but we do possess

two genuine Tiffany products. One is a

sterling silver letter opener that Bob once gave his mother and then

repossessed after her death; he uses it daily to open mail.

Our other Tiffany possession is a small

vase that was given to Bob by a friend who inherited it from his mother. Round-shaped with a narrow mouth, it is two

and a half inches in diameter and serves no practical purpose, nor should it,

given its exquisite fragility. To my eye

it is silverish, and to Bob’s eye golden, but in either case it emits a soft

luster to be marveled at. Bob keeps it

on top of his dresser in a little glass case that he bought specifically to

shelter it, and there it sits, asking only to be looked at and admired.

Our friend John, while serving as

co-executor of the estate of a mutual friend, came into possession of a genuine

Tiffany lamp lacking a few small pieces of glass. He and his fellow executor spent $2800 to

have it repaired, so they could sell it through Christie’s. Christie’s estimated its value at $20,000 to

$30,000, but at auction it drew not a single bidder. Undismayed, Christie’s decided to hold off

for six months and offer it again. At

the second auction it was sold for $18,000; after Christie’s fee and other

expenses were subtracted, the two executors netted $12,000, which as heirs they

split evenly. All of which shows the

value of genuine Tiffany lamps today, for which there is an ongoing market. Because Tiffany’s, to put it bluntly, has class.

It also has a long and interesting history. Charles Lewis Tiffany, the founder, and his

partner John P. Young opened the first Tiffany’s as a “stationary and fancy

goods emporium” in 1837, with the intention of selling not to the moneyed few,

but to the masses. Located at 259

Broadway, opposite City Hall Park, it netted all of $4.98 on the first day,

which hardly suggested success. But the

partners persevered, offering umbrellas, Chinese carvings, portfolio cases,

fans, gloves, and stationery, and on New Year’s Eve, the peak of the holiday

shopping season, they rang up sales of $679.

|

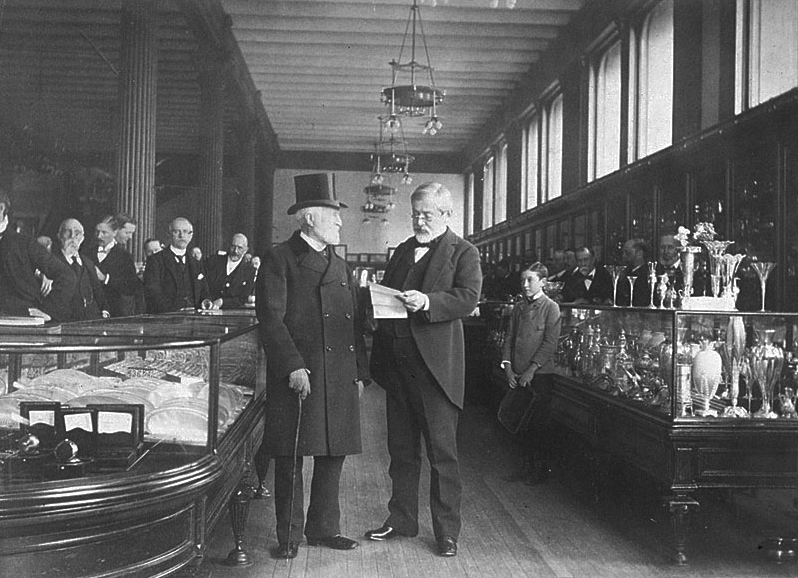

| Charles Lewis Tiffany in his store, circa 1887. |

In the years that followed, Charles Lewis Tiffany

roamed the docks for unusual imports, bargained with sea captains for exotic

items, and acquired a reputation for selling such curiosities as dog whips,

Venetian-glass writing implements, Native American artifacts, Chinese

novelties, “seegar” boxes, and “ne plus ultras” (garters).

Jewelry

was not at first a significant item, but that changed in 1848, when aristocrats

fleeing the revolution in Paris dumped their diamonds on the market, and

Tiffany’s partner Young, just arriving in the city, snapped them up. Arrested as a royalist conspirator, Young

talked his way out of it and survived to forward his trove to Tiffany, who

publicized his partner’s adventures; ironically, it was Tiffany himself whom

the press then christened the “King of Diamonds.”

In 1850 Tiffany opened a Paris branch, thus

acquiring access to European jewelry markets that no American competitor could

match. Years later Charles Lewis Tiffany

would acknowledge that the firm had also acquired the girdle of diamonds of

Marie Antoinette, which had disappeared when the 1848 revolutionaries looted

the Tuileries palace. Breaking the

girdle up into pieces to sell, Tiffany claimed that its authenticity could not

be proven, and thus avoided any awkward revelations about how the item had

migrated from the royal vaults of the Tuileries into his own welcoming palms, a

mystery that remains unsolved today.

His reputation for scrupulosity, his ready

cash, and his swift judgment made Tiffany the city’s leading dealer in jewelry

and Oriental pearls. Always on the

lookout for rarities, in 1856 he bought a perfect pink pearl from a New Jersey

farmer who had found it in his dinner mussels.

He promptly sold it to the Empress Eugénie of France, news of which

precipitated a mass combing of the waterways of America in hopes of finding

another huge triple p: perfect pink pearl.

(None was found.) And when a

Montana prospector unearthed some sapphires and mailed them to him for

appraisal, Tiffany appraised them and immediately sent him a check for

$12,000. But in his store haggling over

prices was not allowed; one paid the tagged price, however astronomical, and

that was that.

|

| Isabella II, before she lost her jewels. |

Not that Charles Lewis Tiffany was

infallible. In 1872 word of a discovery

of diamonds in a mine in Arizona reached New York, and a clutch of speculators,

eager to buy stock in the mine, consulted him.

Shown the diamonds in the rough, he announced, “They are worth at least

$150,000.” The speculators then invested

four times that in the mine, but subsequently a government geologist went to

the site, which was in fact in Utah, and discovered that it had been “salted”

with poor-quality stones from South Africa.

Informed of the fraud, Tiffany confessed, “I had never seen a rough

diamond before.” And he lost $80,000 in

the swindle himself.

As the city spread northward and the

affluent middle class migrated uptown to more fashionable districts, Tiffany

& Co. migrated with them. By the

1860s the firm was at 552 Broadway, occupying an ornate five-story building

with round-arched windows and, over the main entrance, a nine-foot carved-wood

Atlas shouldering a huge clock that was said to have stopped at 7:22 a.m. on

April 15, 1865, the exact moment of Abraham Lincoln’s death. (Painted to look bronze, Atlas would

accompany the firm on its migrations thereafter and overlooks the Tiffany

entrance on Fifth Avenue today.)

And what did one see in Tiffany’s window

in those days? A mishmash of cluttered objects,

some made by Tiffany and some imported: bronze figurines, vases and cups and

goblets, fancy lace fans, jeweled clocks and caskets, ornate silver picture

frames, and draped over everything in profusion, strings of pearls. Such was the bric-a-brac that the Victorians

used to clutter up themselves and their parlors; one can well imagine the

smaller items clustered on the shelves of a whatnot, next to a daguerreotype of

young Danny in his Civil War uniform and, in a fancy frame, a lock of Aunt

Millie’s hair.

|

| Tiffany's, circa 1887. |

Probably not on display was the famous

Tiffany Diamond, weighing 287.42 carats, discovered in South Africa in 1877 and

purchased by the firm for $18,000. The

young gemologist whom Tiffany entrusted with cutting it down studied the

diamond for a year before starting work.

He then carefully cut it down to 128.54 carats, adding 32 facets for a

total of 90, and thus created a dazzling multifaceted gem that, never sold, has

highlighted Tiffany exhibits throughout the world ever since. Only two women have ever worn it: Mrs.

Sheldon Whitehouse at a Tiffany ball in Newport, Rhode Island, in 1957, and

Audrey Hepburn in 1961 publicity photographs for the film Breakfast at Tiffany’s. The film

helped refurbish Tiffany’s then sagging reputation, and for years afterward visitors

coming to the store would ask where breakfast was served. Today the diamond is displayed on the main

floor of Tiffany’s flagship store on Fifth Avenue at 57th Street.

|

| The Tiffany diamond, topped by a bird. Shipguy |

But Charles Lewis Tiffany marketed any

rarity that he thought might sell. In

1858, when the Atlantic cable at last reached Ireland and established a

transatlantic telegraph link, he acquired 20 miles of the cable salvaged from

unsuccessful earlier attempts to lay it, and sold four-inch snippets for fifty

cents apiece, as well cable-adorned canes, umbrellas, paperweights, watch fobs,

and lapel pins that the public snapped up eagerly – so eagerly that the police

had to restrain the crowds.

In the late nineteenth century Tiffany’s

produced fine silverware that won international prizes, and in 1894 built a

huge factory in Newark to make such luxury items as the silver plate favored by

Delmonico’s, as well as exotic leather goods and engraved stationary. By now, obviously, the firm was catering to

the rich and famous.

|

| Tiffany no. 2, circa 1908. |

The

successors of the Tiffany family abhorred publicity, and under their direction

the firm produced staid and predictable merchandise. By the 1950s sales had shrunk to half the level

of the generation before, and the firm risked bankruptcy. Whether the general public was aware of this

is uncertain, since when I came to New York in the 1950s the name “Tiffany’s”

still had cachet, suggesting fine products for the elite who were willing to

pay accordingly. Things changed for the

better with the coming of Walter Hoving, the Swedish-born American businessman

who became president of Tiffany & Co. in 1955 and held that post until

1980.

A tall and distinguished-looking man, impeccably

tailored, Hoving began by getting rid of everything in the store that did not

meet his standards, marking down silver matchbook covers to $6.75 and emerald

brooches to a mere $29,700. Hoving has

been called a snob, but under his guidance the quality of the merchandise

improved and customers flocked. Among

the shoppers on several occasions was President John F. Kennedy, whom Hoving

dealt with personally in private, and who bought items for his wife. When Kennedy asked if the President got a

discount, Hoving pointed to a portrait of Mary Lincoln wearing a strand of

Tiffany pearls and replied, “Well, President Lincoln didn’t receive one.” So Kennedy paid full price.

|

| The Trump Tower (the tall one, of course). InSapphoWeTrust |

Hoving left in 1980 because Tiffany’s had

been acquired by Avon Products in 1979.

A buyout by management followed, and in 1987 Tiffany’s became a public

company and raised $103 million through the sale of its common stock. During the 1990-1991 recession it turned to

mass merchandising, presented itself as affordable to all, and advertised

diamond engagement rings starting at $850.

A brochure entitled “How to Buy a Diamond” went out to 40,000 people who

had dialed a toll-free number. The

founder, Charles Lewis Tiffany, was adept at publicizing his wares, but what he

would have thought of these modern expedients I leave to the viewers’

imagination.

One thing is clear today: genuine Tiffany

lamps are still prized items that sell for tens of thousands. But plenty of imitations are on the market,

since they are advertised online for as little as $64.78. So how does one tell the authentic lamp from

the knockoffs? Some clues are very

technical; here are several simpler things to look for:

· A bronze base.

Not wood, plastic, brass, or zinc.

· The color of the glass changes when the lamp is lit.

· A Tiffany Studios stamp and a number on the base.

· Signs of age; it won’t look brand new. (But some fakes mimic age on the base.)

· A ring of grayish lead in the hollow base.

· The glass shade, if knocked gently, should rattle.

Also, a buyer should ask for

a money-back guarantee and beware of any

shop that won’t give one. Not

that there’s anything wrong with cheapie Tiffany lamps that don’t claim to be

authentic; they have their place in the market.

It’s the ones that are deliberately made to look like and sell as authentic

ones that cause trouble.

One almost final note: in 2013 a former

Tiffany vice-president was arrested and charged with stealing more than $1.3

million in jewelry. This development,

for sure, would make founder Charles Lewis Tiffany turn over in his Green-Wood

Cemetery grave in Brooklyn.

|

| Tiffany's today. David Shankbone |

Since 1940 Tiffany & Co. has occupied

a granite and limestone building on Fifth Avenue at 57th Street,

with a grandiose stainless-steel entrance overlooked by the nine-foot near-naked

Atlas that has been shouldering a clock for Tiffany’s since 1853. And what does Tiffany’s offer today? Their website promises free shipping on

orders of $150 or more, and advertises gifts under $500. Clearly, they want to appeal, if not to the

masses, at least to the modestly affluent.

But modest they themselves aren’t, claiming to be “the world’s premier

jeweler and America’s house of design since 1837.” Among their offerings is an item labeled

“quintessential Tiffany,” a dazzling sixteen-stone ring in 18-karat gold with

diamonds from Parisian designer Jean Schlumberger, a marvel whose “timeless

perfection … deserves a place of honor in every stylish woman’s jewelry

box.” The price? $9,000, which is reasonable indeed when

compared to Schlumberger’s Croisillon bracelet in 18-karat gold for

$30,000. And remember, no haggling.

|

| Atlas still holds the clock today. Meg Lessard |

A bulletin from the health-care front. My eye doctor, a very no-nonsense type who

wastes no time on small talk, wanted me to get an eye-drop refill immediately

from the pharmacy on the ground-floor of the clinic. One of her assistants phoned the clinic to

order the refill, then informed me, “The pharmacy needs a twenty-four notice to

–” Hearing this, my doctor seized the

phone, jabbered fiercely, then hung up and announced, “You can pick it up downstairs

now.” Her two assistants who witnessed

this were smiling already. “We all know

where the power is,” I said softly to them, and they grinned from ear to ear.

End of story? No way.

When I went down to the pharmacy, the pharmacist informed me that if I

got the refill now, my insurance wouldn’t cover it, so it would cost $120. But if I waited two days, the refill would be

covered and cost only $35. So I chose to

wait. Moral of the story: In the health-care universe doctors are gods,

but insurance companies are super gods.

So it goes.

Coming soon: The rich of today, who make those rags-to-riches

nineteenth-century types look absolutely quaint. We’ll get with it with hedge fund managers,

corporate raiders, and the like. And

guess who is the richest New Yorker? You

may – or may not – be surprised. (Clue:

it isn’t Donald Trump.)

©

2015 Clifford Browder

No comments:

Post a Comment