1845

They are always there and we

acknowledge the fact with our envy or our resentment. And they’ve always been especially

conspicuous in New York City. So let’s

have a look at who they are – or were – and how they got their money, starting

in 1845. Why 1845? Because that year saw publication of the

sixth edition of Wealth and Biography of

the Wealthy Citizens of New York City, offering an alphabetical list of all

persons in the city believed to be worth $100,000 or more, with the sums

appended to their name, along with, as the preface states, “interesting

biographical and historical matter, as derived from the consultation of books

and living authorities.”

All of which suggests a compendium of The Wall Street Journal, Forbes, and People magazine, a formality worthy of Barron’s spiced up with some juicy

tidbits like those featured in the gossip magazines prominently displayed in

supermarket check-out lanes. But

remember, this was 1845, not 2015. And

the publication was answering a need, since in those days there was no official

agency offering credit ratings of individuals or businesses, and this lack

became obvious during the Panic of 1837 and its aftermath, when bankruptcies

multiplied throughout the city and the nation. People wanted to know who was financial sound and who was not. So Moses Y. Beach, publisher of The

Sun, a prominent New York daily, got

busy and produced this publication. And

if $100,000 sounds like a low entry level for admission to its pages, it’s

worth remembering that an 1845 dollar would be worth $31.25 today, so multiply

all the figures accordingly.

So who had the biggest fortunes in

1845? There’s no doubt about #1, John

Jacob Astor, whose $25 million made in the fur trade and New York real estate

established him as the richest man in the entire country and earned him two

full columns of comment in tiny print, more than anyone else in the

publication. He is hailed as a truly

great man, a German immigrant who arrived on these shores as a common steerage

passenger, a poor uneducated boy who didn’t speak English, but who through his

own industry accumulated a fortune “scarcely second to that of any individual

on the globe, and has executed projects that have become identified with the

history of this country, and which will perpetuate his name to the latest

age.” His princely house on Lower

Broadway, furnished with “richest plate” and works of art, and staffed with an

army of servants, including “some from the Empire of the Celestials,” is viewed

with admiration and awe. Moses Beach

estimates his income at $2 million a year ($62 million in today’s dollars),

which for 1845 was an unprecedented sum.

Also noted is Astor’s gift of $350,000 for the creation of a library in

New York City that would bear his name, and that in time merged with two other libraries to create the New York Public Library of today.

All in all, the career of John Jacob is presented to the reader as a

classic but exceptional example of rags to riches, a theme that Beach's preface

promised to celebrate. But his portraits suggest only riches and dignity, no hint of rags or steerage.

|

| John Jacob Astor, an 1825 portrait. Dignity, plus a neck cloth (no ties as yet). |

Sadly, the subject of this encomium, now

82 years old, was suffering from ill health.

White-haired and portly, with an iron jaw under folds of loose flesh, he

walked only with the help of attendants, took short carriage rides, struck

others as dignified but tired. Yet he

was still alert when it came to moneymaking and tight with his pennies, for in

his mind he was still the penniless youth who came to this country in

steerage. While dining with a friend

once in a new hotel, he eyed the proprietor and announced to his friend, “This

man will never succeed.” “Why not?”

asked the friend. “Don’t you see what

large lumps of sugar he puts in the sugar bowl?”

The second richest man in the city, with

$10 million according to Moses Beach, was Stephen Whitney, another

rags-to-riches story, who started out poor as a retail liquor merchant, went

into the wholesale liquor business, speculated with great success in cotton,

and also invested in real estate.

Liquor, cotton, and real estate – three sure ways for a shrewd New

Yorker to make money, and Beach assures us that Whitney was very shrewd, and

also “very close in his dealings.” Is he

remembered today? Hardly. Unlike old John Jay and his descendants,

Whitney had little time for philanthropy.

|

| Stephen van Rensselaer no. 3 |

The third largest New York City fortune,

matching Whitney’s at $10 million, was not a living person but the estate of

Stephen van Rensellaer (d. 1839) of Albany, who qualified for inclusion by

virtue of his ownership of hundreds of lots in New York City. But city real estate, however substantial,

was simply a shrewd side investment, since Stephen van Rensellaer (the third of

that name) had been the fifth in a long line of Dutch patroons, lords of the

huge semi-feudal estate of Rensellaerswyck, comprising vast lands on either

side of the Hudson River both above and below Albany. Whether a vast feudal estate where a

Rensellaer lorded it, however benevolently, over 3,000 tenants was appropriate

in a modern, democratic age, Moses Beach never questions, though the tenants

were beginning to do so in what would become the anti-rent movement and put an

end to the anachronistic patroonship.

Other multimillionaires of 1845 include

William B. Astor ($5 million), John Jacob’s son, another shrewd investor in

Manhattan real estate; Peter G. Stuyvesant (($4 million), a descendant of the

one-legged last Dutch governor of New Amsterdam, from whom Peter G., Beach

informs us, has inherited and kept the silver spoon; and James Lenox ($3

million), who inherited from his father and, so Beach assures us, “devotes

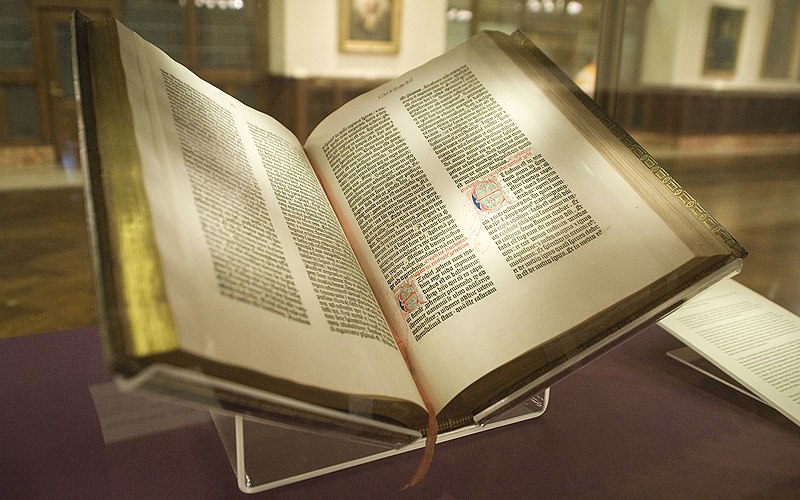

himself chiefly to pious objects.” Actually,

he was acquiring rare manuscripts and books, including Bibles, and paintings,

busts, engravings, and other art works for what would become the most valuable

such collection in the hemisphere and be housed in the Lenox Library, which in

time would be consolidated with two other libraries to create the New York

Public Library. If with the Astors,

father and son, one sees money-getting finding time for philanthropy, James

Lenox shows inherited wealth devoting itself almost exclusively to cultural

activities from which the whole community will benefit in time. Sooner or later, money begets culture.

|

| A Gutenberg Bible, circa 1455, in the Rare Books Division of the New York Public Library. From the Lenox Library. One of James Lenox's "pious objects." NYC Wanderer |

Of the eleven other millionaires, three

names stand out, albeit for very different reasons. Peter Harmony is said to have come to the

city as a poor cabin boy born in the West Indies, and to have lately retired

from the shipping business with a princely fortune ($1.5 million). (He was in fact an immigrant from

Spain.) “Some of his ships to Africa, it

is said, have brought out cargoes that have paid a profit equal to the

difference in price between negroes in Africa and Cuba.” Which is a pretty clear reference to the

illegal but lucrative and still flourishing slave trade that brought Africans

to the Spanish colony of Cuba, where sugar plantations still provided a market,

and officials looked the other way.

Jonathan Thorne is described as “the very

pink and glass of fashion in the Parisian circles,” and this despite his

descent from old Quaker ancestors who

would wonder at his “gorgeous private chapel at his imperial mansion in the

French capital.” “What changes in the

wheel of fortune,” Beach adds, “from an humble purser in the navy?” How a humble purser achieves a fortune of $1

million and a mansion in Paris, Beach fails to explain. But he is clearly on the side of hard work and

business, and not on the side of fashion.

Cornelius Vanderbilt, credited with $1.2

million, rates only a short paragraph, since Moses Beach could not anticipate

the future railroad king and titan of finance.

But Beach recognizes energy when he sees it: “Of an old Dutch root. Cornelius has evinced more energy and ‘go

aheadativeness’ in building and driving steamboats and other projects than ever

one single Dutchman possessed.” It takes

the American hot sun, he adds, to clear off the fogs of the Zuyder Zee and wake

up the phlegm of a descendant of old Holland.

Though full of admiration for many, Moses Beach

was at times ready to pronounce a moral judgment as well. Just hear him, no doubt with memories of the

Panic of 1837 and its aftermath, praise a team of mechanics who became

celebrated engravers of bank notes. By

contrast, he asks, what utility is to be seen in “swindling stock operations …

deemed more reputable than the walks of mechanic life.” No longer, he insists, can dreaming

speculators and fancy operators sneer at the “brawny arms” and “russet palms”

of the honest laborer. The false system

of credit that once prevailed has been eliminated, he declares, “breaking up the

nests of lounging, idle upstarts, that like mushrooms on a dung-hill sprouted

up out of the masses of rag-paper and spurious capital.” And what would Mr. Beach say today, in the

wake of our own recent financial convulsion, when such novel phenomena as

collateralized debt obligations and credit default swaps appeared, and still

appear, to the bafflement of many and the enrichment of a few?

The first half of the nineteenth century in

New York was the age of the merchants, when success in trade brought

wealth. Most of Beach’s subjects dealt

in things you could see, touch, taste, or smell: silks, cotton, tea, furs,

chinaware, brandy, ships, and real estate.

And in a few cases, slaves. Not

that rich marriages and inherited wealth didn’t help.

Among the names that had yet to achieve

their greatest success was Phineas T. Barnum, proprietor of the American Museum

and guardian of the celebrated midget Tom Thumb. Reported to be currently in Europe exhibiting

said Thumb, “by whom he is coining money,” the master of showmanship and humbug

is said to be worth $150,000. Yet his sensational

promotion of Jenny Lind, the Swedish Nightingale, lay five years in the future,

and his traveling circuses had yet to be organized.

Another New Yorker just at the start of

his career is Irish-born Alexander T. Stewart, worth $800,000, already a

“celebrated Dry Good Merchant of Broadway whose shop is the grand resort of the

fashionables.” Yet he rates only a mere

six lines. Rest assured, we will hear of him again.

For an unusual name no one can match

Preserved Fish, a sea captain turned shipping merchant worth $150,000, and

president of the Tradesmen’s Bank. Beach

presents him as “an example of an uneducated man, of strong mind, exercising

great influence in his sphere.” But how

he got his outlandish name Beach does not explain. Other sources state that Fish was of Huguenot

stock, and that his father and grandfather bore the same first name, which they

pronounced in three syllables, pre-SER-ved, meaning “preserved from sin” or

“preserved in grace.”

|

Catharine Sedgwick, an illustration

probably dating from the early 1800s.

|

Women are far and few in Moses Beach’s

compilation, and then almost always as widows or heirs of males. The one exception is Catharine Sedgewick, a

“distinguished novelist” famous for her “New England Tales,” a “religious satire

published some 20 years since.” Though

she received a “snug” fortune by inheritance, she “has reaped a large income

from her books, the circulation of which exceeded those of any American

author.” Though she seems to have

resided in Massachusetts, she gets a princely seventeen lines and is credited

with $100,000. Here, then, is an

early example of the “scribbling

females” that Nathaniel Hawthorne would acknowledge with scorn, writers whose

novels, not rated highly today, were widely read in their time, often bringing

in income that the less pecunious male writers of the day envied and resented

bitterly.

1863

No other source that I know

of gives as comprehensive and colorful an account of New York’s wealthy as does

Beach, but the income tax imposed by the federal government during the Civil

War lets us know who then were the wealthiest citizens of New York, for in January

1865 the enterprising but often controversial New York Herald published the names of prominent citizens paying

the tax, prompting protests at this invasion of privacy, and a New York Times editorial observing that

“the most glaring and shameless frauds are practiced in the return of incomes,

and in the assessment of taxes upon them.”

Men living at the rate of anywhere from $10,000 to $30,000 a year, it

insisted, were put down as having no income at all, an assertion that the New York Tribune echoed.

And that wasn’t the end of it, for later

in that same year of 1865 the American News Company published The Income Record: A List Giving the Taxable

Income for the Year 1863, of Every Resident of New York. The publisher’s stated goal was “to

satisfy an imperious public curiosity, which thus far has been only partially

gratified by the public journals”; to let citizens decide whether their

neighbors had been honest in stating their income; and to provide trustworthy

statistics to future legislators for revisions of the tax laws. Many a moneyed gentleman, one suspects,

trembled in his ruffled shirtfront and shiny boots at the prospect of having

his income revealed yet again, and so authoritatively, to the public.

So who, according to this tabulation, were

the wealthiest citizens of 1863? The top

three:

A.T.

Stewart $1,843,637

William

B. Astor $838,525

Cornelius

Vanderbilt $680,728

All three appeared in Moses

Beach’s tabulation of 1845, but times have changed and they now eclipse all

others in wealth.

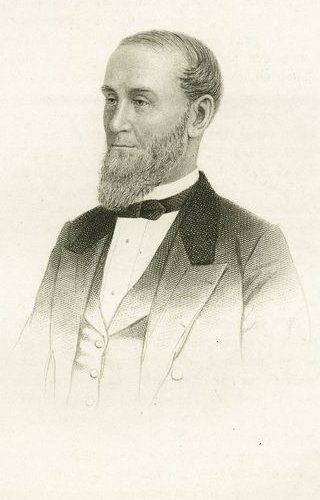

|

| Alexander T. Stewart, circa 1860. Beards and neckties are in, neck cloths are out. |

Stewart’s income astonished the public and

probably establishes him as the most honest of the lot. His new department store on Broadway at 10th

Street, a six-story cast-iron structure with a glass-dome skylight, built in

1862 and occupying most of a whole block, employed some 2,000 people, had hydraulic

elevators, and offered fashionable society a wide range of fabrics, scarves,

shawls, lamps, carpets, bric-a-brac, and toys.

Hailed today as the father of the

modern department store, this generously bearded gentleman prospered to the

point of being considered – for a while – the richest man in the country.

|

| Stewart's department store, the granddaddy of Bloomingdale's, Macy's, and Marshall Fields. |

|

| William B. Astor circa 1850, looking just as formal, dignified, and (let's face it) stodgy as his father. |

William B. Astor, the son of old John J.

and his chief heir, was heavily invested in New York City real estate, earning

him the name of “the landlord of New York.”

He also gave money to the Astor Library founded by his father. Upon his father’s death in 1848, William was

considered the richest man in America with a fortune of $14 million, which

makes his 1863 declaration of annual income of $838,525 perhaps a bit

suspect. Photographs reveal a rather

full-faced man, clean-shaven with long sideburns and a hint of jowls, a

competent heir who lived a profitable but uneventful life devoid of his

father’s eccentricities and flair.

If Commodore Vanderbilt’s figure of

$680,728 likewise seems to err on the side of modesty, it’s worth remembering

that in 1863, having sold his ships, he was just beginning to acquire the

railroad empire that would increase his fortune vastly and make him the richest

man in the country, referred to endearingly in the late 1860s as Old Sixty

Millions. In photographs Vanderbilt

appears tall and erect, with a strong nose and a square jaw, his gray hair

turning strikingly white. Beside such a

figure the other two top moneybags of the day, Stewart and Astor, seem just a

bit bland, but then, anyone compared to the vibrant and often ruthless

Commodore would have come off bland indeed.

This supremely pecunious trio – Stewart,

Astor, and Vanderbilt – resembled the wealthy of 1845 in that they dealt in

tangibles: a department store, real estate, and railroads. And if Astor’s making a fortune in real

estate and being known as the landlord of New York didn’t necessarily benefit

society at large (who loves a landlord anyway?), Vanderbilt’s New York Central

line got people from New York to Chicago and back efficiently, and Stewart’s dry goods

palace dazzled them with its offerings of this world’s goods.

The Gilded Age

|

| Caroline Schermerhorn Astor -- the Mrs. Astor -- entertaining at one of her balls. The ladies' gowns rustle on the floor but are decidedly low-necked. |

The Civil War ended in 1865,

following which came the so-called Gilded Age, when the rich dressed rich,

paraded about in fancy turnouts, built palatial mansions, raced their yachts,

hitched their moneyed daughters to impoverished European noblemen (most of them

accomplished debauchees), and generally enjoyed the good life free from such

annoyances as an income tax. On the

Upper Fifth Avenue the Vanderbilts and Astors leapfrogged over one another,

building ever more palatial mansions that made their rivals’ residences lower

down on the avenue look opulently shabby, while Mrs. Astor – the Mrs. Astor, whose mail required no

other designation to reach her – welcomed annually to her ballroom, which held

just four hundred guests, the select four hundred persons deemed by her to be

socially acceptable. Needless to say,

the simplicity of an earlier age, when flaunting your wealth was frowned on,

had vanished, and often as not the pampered descendants of those earlier

moneymakers felt no need to smirch their hands with toil.

On

this happy note I will end. The rich of

the twentieth and twenty-first centuries – a very different species -- will be

looked at in a future post. As well as The Donald, who merits a post all his own.

The book: The selection of posts from this blog is available in print version at $14.95 (or cheaper), and as an e-book with Nook, Kindle, etc., for $3.99. One of the online come-ons describes it in a unique brand of English: "Stories excluding the Authorization Agitating Metropolitan area in the Copernican universe … art critic Clifford Browder leaves no wallpaper unturned … a invest that so muchness are worthy to caw home." One copy of the print version is offered free on a Goodreads giveaway through November 18.

The book: The selection of posts from this blog is available in print version at $14.95 (or cheaper), and as an e-book with Nook, Kindle, etc., for $3.99. One of the online come-ons describes it in a unique brand of English: "Stories excluding the Authorization Agitating Metropolitan area in the Copernican universe … art critic Clifford Browder leaves no wallpaper unturned … a invest that so muchness are worthy to caw home." One copy of the print version is offered free on a Goodreads giveaway through November 18.

Coming soon: Tiffany’s: The magic of their lamps (and how

to tell a genuine one from a fake), the tiny lustrous vase in our apartment, a great fraud, and

how The Donald bamboozled the Tiffany’s of today. Plus a mystery: How did Marie Antoinette’s

diamonds end up over here?

©

2015 Clifford Browder

No comments:

Post a Comment