Nineteenth-century New York was too drunk on

the idea of Progress (usually capitalized) to worry about preserving anything. It was Young America, it was Go Ahead,

breaking free from the old and embracing wholeheartedly the new. Obsessed with Bigger, Better, Faster, it

didn’t need to grasp the ideas of the marquis de Condorcet, the eighteenth-century

philosophe whose buoyant optimism saw humanity as marching ever onward and

upward; indeed, New Yorkers almost daily saw proof of Progress right there before

their eyes. Almost daily, as the city’s

growth exploded, they learned of a cornerstone laying, a bridge opening, a ship

launching, or the laying out of yet another street, events marked with

appropriate ceremonies, speeches, and cheers, and sometimes even the booming of

cannon. One amazing change after another

transformed their lives: the steamboat, the railroad, indoor plumbing, the

telegraph, the elevator, electricity, the telephone, and by the end of the

century, the automobile. They were

fiercely convinced that their city was the locomotive pulling the rest of the

nation faster and faster into the future.

Spreading northward on the narrow,

cigar-shaped island that was Manhattan, the city was in constant flux, tearing

down and building up. In the name of

Progress old cemeteries were dug up and their bones scattered, so the property

could be developed, and pious congregations joined the general migration

northward, their abandoned churches becoming warehouses, stables, markets, tenements, and

even, alas, houses of prostitution. And

when the Great Fire of 1835 destroyed the whole Wall Street area, including the

Merchants’ Exchange, an elegant marble-faced neoclassical building topped by a

soaring rotunda, the fever to rebuild was such that work immediately began on

lots still warm from the fire. On the

site of the old Merchants’ Exchange, where everything from steamboats to whale

oil and molasses had been sold, a new exchange rose in Greek Revival style,

even more massive and impressive, fronted by twelve soaring marble columns and

topped by a dome. As for the loss in the

fire of the last old Dutch houses in Manhattan, not a tear was shed for those

hopelessly quaint, hopelessly old-fogey one- or two-story brick structures, their

stepped gable ends facing the street. The very notion of landmark preservation would

have struck the citizens as needless, alien, and outlandish; it would have to

wait a century or more.

Spreading northward on the narrow,

cigar-shaped island that was Manhattan, the city was in constant flux, tearing

down and building up. In the name of

Progress old cemeteries were dug up and their bones scattered, so the property

could be developed, and pious congregations joined the general migration

northward, their abandoned churches becoming warehouses, stables, markets, tenements, and

even, alas, houses of prostitution. And

when the Great Fire of 1835 destroyed the whole Wall Street area, including the

Merchants’ Exchange, an elegant marble-faced neoclassical building topped by a

soaring rotunda, the fever to rebuild was such that work immediately began on

lots still warm from the fire. On the

site of the old Merchants’ Exchange, where everything from steamboats to whale

oil and molasses had been sold, a new exchange rose in Greek Revival style,

even more massive and impressive, fronted by twelve soaring marble columns and

topped by a dome. As for the loss in the

fire of the last old Dutch houses in Manhattan, not a tear was shed for those

hopelessly quaint, hopelessly old-fogey one- or two-story brick structures, their

stepped gable ends facing the street. The very notion of landmark preservation would

have struck the citizens as needless, alien, and outlandish; it would have to

wait a century or more.

The cult of Progress continued well into

the twentieth century and took on a very American air with the appearance in

the 1920s and 1930s of that distinctly American phenomenon, the

skyscraper. The Chrysler Building and

the Empire State Building were hailed as New World wonders, and Rockefeller

Center, built in the very depths of the Depression, seemed dazzlingly grandiose

and daring. The Art Deco style

characterizing all three was a sharp break with the Beaux Arts style of Grand

Central Station and the New York Public Library, and with anything that smacked

of the Old World. Creating such marvels,

New York was still the locomotive hauling the rest of the nation into the world

of tomorrow.

The World of Tomorrow, indeed, was the

theme of the New York World’s Fair of 1939, and industrial designer Norman Bel

Geddes’ popular exhibit Futurama presented a model of the world twenty years

into the future, with vast suburbs, segregated highways allowing a free flow

of traffic and pedestrians, and an 18-minute ride on a conveyor system giving

spectators a simulated aerial view of the panorama.

I never saw the New York World’s Fair, but at a very tender age was taken to A Century of Progress, the 1933 world’s fair celebrating the centennial of the city of Chicago, whose ill-timed theme contrasted sharply with the woes of the Depression. But not even a depression could squelch the cult of Progress.

|

| The Futurama exhibit, showing a street intersection in the City of Tomorrow. I leave it to residents and visitors to decide if Bel Geddes' vision has been realized in New York. |

|

| Poster for the Chicago World's Fair. |

I never saw the New York World’s Fair, but at a very tender age was taken to A Century of Progress, the 1933 world’s fair celebrating the centennial of the city of Chicago, whose ill-timed theme contrasted sharply with the woes of the Depression. But not even a depression could squelch the cult of Progress.

The prime New York developer of the twentieth century was Robert Moses (1888-1981), who pursued public works – and pursued them ruthlessly – under six New York State governors and five New York City mayors. (See post #78, The Hercules of Parks.) In the city he transformed Pelham Bay Park and Riverside Park, completed the Triborough Bridge, built the West Side Highway, and created Lincoln Center, the United Nations Headquarters, Co-op City, Stuyvesant Town and Peter Cooper Village, and the New York Coliseum. And that is only a partial list of his accomplishments. New York City has always dreamed big, and Moses dreamed bigger than anyone. But he wasn’t just a dreamer, he built. And to build his grandiose projects he flattered, schemed, lied, and pressured, and so became, in the words of his biographer, the biggest builder the world had seen since the pharaohs of ancient Egypt. But to realize his dreams, he thought nothing of invading old neighborhoods, tearing them apart, destroying them, and displacing thousands of residents for the sake of the New.

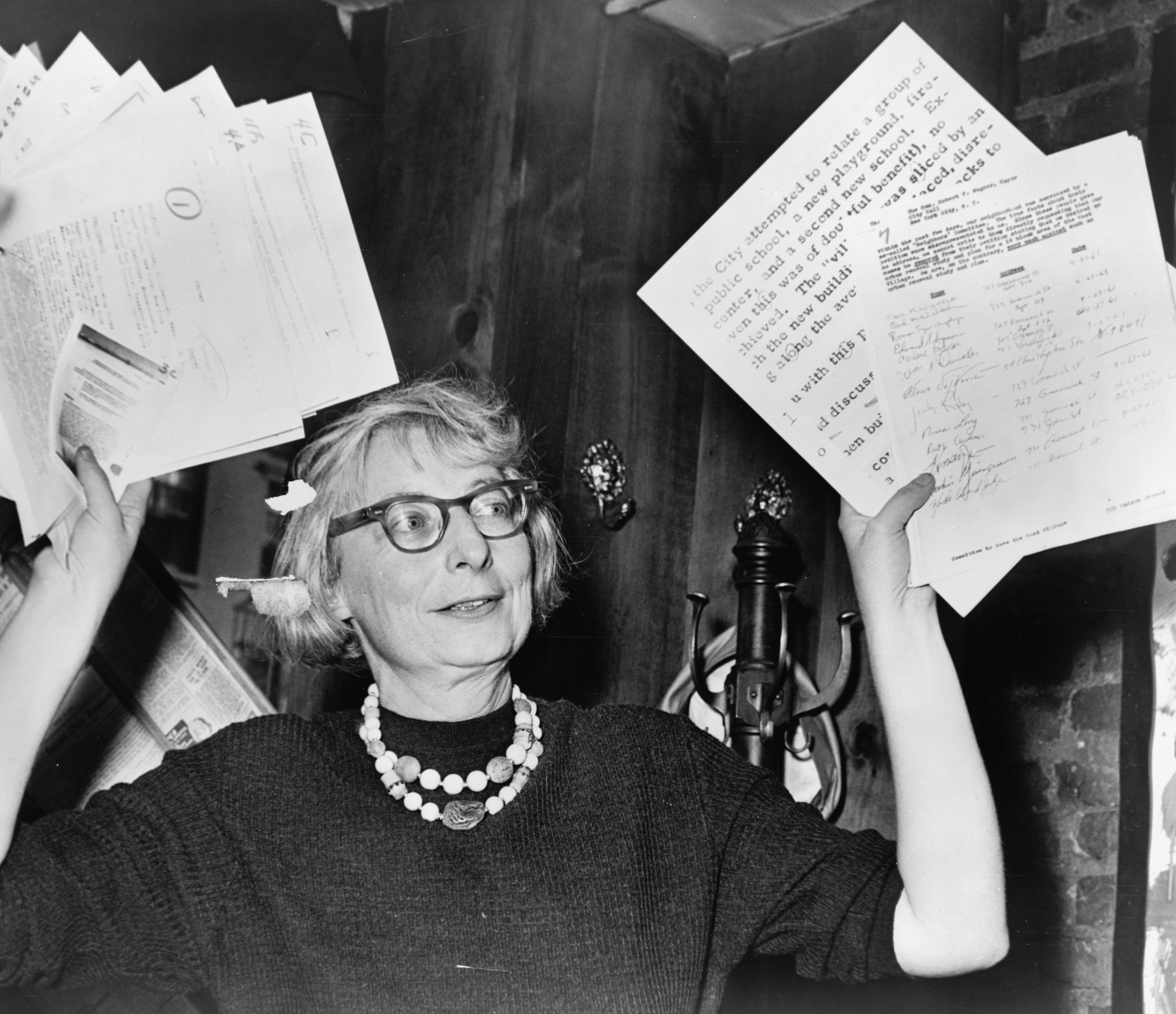

In 1952 Moses announced a plan to have two

streets flank the Washington Square Arch and run on south through Washington

Square Park, obliterating the fountain.

This assault on a beloved green space in Greenwich Village aroused the fierce

opposition of local residents, including former First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt,

and under the leadership of urban activist Jane Jacobs they launched a campaign

to save the park and ban all vehicles from it.

A long and complicated legal fight followed with many ups and downs, but

David finally triumphed over Goliath: in 1963 the park was saved and all

vehicles were banned from it forever.

|

| The Washington Square Arch today. No streets flanking the arch and no vehicles. David Shankbone |

This and a few other rare defeats of

Robert Moses signaled, by the 1960s, a

significant change in the attitude of New Yorkers toward grandiose projects

created at the expense of small neighborhoods. Especially influential was Jane Jacobs’s book The Death and Life of Great American Cities (1961),

which denounced urban planning as destructive of organic city neighborhoods

while replacing them with sterile urban spaces.

But even as Jacobs and her fellow Villagers fought off the attack by

Moses, developers were demolishing old buildings in the Village and replacing

them with big new apartment buildings with fancy lobbies and uniformed doormen,

and names that oozed high culture: the Van Gogh on Horatio Street, and the

Cézanne and the Rembrandt on Jane Street, the very street where I was then

living. Passing these unlovely but well-scrubbed

behemoths as I often did, I wondered when a Puvis de Chavannes or a Whistler might

appear, or perhaps a Bouguereau, though this last would be ill-advised, since

Americans might pronounce it “Bugger.”

Only with the creation of the Greenwich Village Historic District in

1969 did these depredations stop, and even then the district’s borders zigged

and zagged capriciously, stopping just south of 14th Street on the

north and short of the Hudson River on the west, while reaching only to

Washington Square on the south and east.

The heart of the Village was preserved, but not all of it.

What finally triggered a widespread

movement to protect city landmarks was the demolition in 1963 of the old Penn

Station, a 1910 Beaux Arts masterpiece built by the celebrated firm of McKim,

Mead & White. The pink granite façade

on Seventh Avenue between 31st and 33rd Streets featured

a colonnade of Tuscan columns, and the high-vaulted waiting room inside, patterned

on the Baths of Caracalla in ancient Rome, was the largest enclosed space in

the city and one of the largest in the world.

Adjoining the waiting room was a concourse of glass and wrought iron,

equally vast and imposing. Photographs of

the exterior and interior give breathtaking views, and aerial photographs of

the ensemble, which occupied two whole city blocks, are awesome.

| What we lost: the main waiting room. |

|

| What we lost: the concourse. |

Demolished? one asks in wonderment. A monument as magnificent as it was colossal

-- destroyed? How could this be? There were protests at the time, but the

Pennsylvania Railroad, faced with dwindling revenues and the burdensome expense

of maintaining the existing structure, had sold the air rights to a developer

who planned to build a new Madison Square Garden on the site. Of course there would be a new Penn Station,

and air-conditioned. Much smaller in

size, it was built below street level – the cramped mediocrity of a station

that travelers are stuck with today. Comparing

the old and new stations, an architectural historian remarked, “One entered the

station like a god; one scuttles in now like a rat.” Expedience and cost effectiveness had triumphed

over magnificence, and with a touch of irony as well: Stanford White, the

famous architect whose firm had created the old Penn Station, had been shot to

death in an earlier Madison Square Garden that he had also built; now the

construction of yet another Madison Square Garden, the fourth of that name, was

the pretext for demolishing his masterpiece.

|

| What we got: the Penn Station concourse today. Glitzy, flat-ceilinged, uninspired and uninspiring. Alan Turkus |

The full significance of the city’s loss

registered with me only when I saw a New

York Times photograph showing some of the station’s huge columns lying

abandoned in a field in New Jersey, soon to be relegated to a Meadowlands

landfill. One wanted to denounce the

railroad management and the developer, but weren’t we all to some extent

guilty? Hurrying through those

remarkable vaulted spaces, we were too preoccupied with catching our train to

pause and absorb the splendor all around us.

Belatedly, a firestorm of protest led to

the creation, in 1965, of the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission,

an agency charged with protecting all buildings and districts deemed

architecturally and historically significant.

The Real Estate Board of New York vigorously opposed the commission’s

creation, but in time came to realize that the commission’s work could actually

increase a property’s value. By law the

commission consists of eleven commissioners appointed by the mayor and must

include at least three architects, a historian, a city planner or landscape

architect, a real estate agent or developer, and at least one resident of each

of the city’s five boroughs. To be

declared a landmark, a building must be at least thirty years old. A property owner can continue to use a landmarked

building, but cannot demolish or alter it without the commission’s approval. As a result, many an old building stands with

its façade intact, though the interior has been gutted and renovated.

As of 2014, more than 31,000 properties

have been designated landmarks, most of them in 110 historic districts and 20

historic district extensions in all five boroughs. Historic districts include Greenwich Village,

the Meatpacking District, SoHo, Wall Street, and South Street Seaport in

Manhattan; Brooklyn Heights and Park Slope in Brooklyn; Grand Concourse in the

Bronx; Jackson Heights in Queens; and Seaview Hospital in Staten Island. One of the commission’s greatest

accomplishments was the preservation of Grand Central Terminal, when Penn

Central tried to alter the structure and top it with an office tower. But the commission’s decisions are often controversial and far from

unanimous, and they can be appealed.

Recently the mere threat of the

commission’s disapproval forced the Frick Collection to abandon its plan to

demolish a garden beloved of New Yorkers on East 70th Street so the

museum could build an unlovely six-story addition. (See post #142 on MOMA and the Frick, August

31, 2014.) The garden, dating from 1977,

is the creation of the distinguished British landscape artist Russell Page and

his only completed work in the city.

Though only a “viewing garden,” meaning that the public can view it from

the fence but not enter it, it is a precious bit of greenery in a city starved

for greenery, with a rectangular pool surrounded by gravel paths and boxwood

hedges. Surprised by the intensity of opposition

to their expansion plan by a coalition of architects, landscape designers, and

preservationists, Frick officials finally yielded and agreed to explore

alternative plans. The opposition, after

all, is motivated by a deep love for the Frick as it is.

Encouraging as the creation of the

Landmarks Preservation Commission was, concerned citizens wanted an organization

focused specifically on New York City.

So in 1973 a small group of architects, lawyers, planners, writers, and

preservationists joined together to found the New York Landmarks Conservancy,

which works to preserve and reuse the city’s architecturally significant

buildings. The conservancy modeled its

work on the Nature Conservancy’s efforts to acquire, hold, and manage

endangered lands. Financed mostly by

donations from the public, the Landmarks Conservancy works closely with owners

and community groups in all five boroughs to safeguard landmarked buildings,

and campaigns to get landmark status for buildings not yet designated as such. It even makes grants and low-interest loans

to help finance renovation and restoration projects throughout the city.

The conservancy insists that it is not

opposed to new development, provided it doesn’t endanger existing structures

that merit preservation. For example, many

Upper East Side “curtain wall” office buildings – those big glass boxes built

in the 1960s and 1970s -- it considers culturally insignificant and ripe for

replacement, which of course means demolition.

While my personal opinion weighs lightly in such matters, I’ll chime in

anyway: all that glass bores me; good riddance.

Though one wonders what will replace it: wonders, or more monstrosities? (There are a few other architectural horrors

that I could easily part with – the Maritime Union building on Seventh Avenue,

for instance, and the New School’s looming oddity with zigzag windows at Fifth Avenue

and 14th Street -- but no matter.)

|

| The Lever House at 390 Park Avenue (1950-52). One that I and the Landmarks Conservancy could do without. Beyond My Ken |

|

The New School University Center at Fifth Avenue and 14th Street: another that I could do without. MusikAnimal |

Thanks to the society’s efforts, the

Gansevoort Historic District was created in 2003, and the South Village

Historic District in 2013. And just as

Robert Moses was the bête noire of preservationists in the 1960s, so New York

University, with its perennial plans for expansion, has become the bugbear of

GVSHP. In 2014 the society and other

plaintiffs won a case against the university’s massive 20-year expansion plan,

only to see the ruling overturned on appeal, following which the plaintiffs in

turn appealed to the state’s highest court.

Preserving old buildings is a constant battle with many antagonists, the

Real Estate Board of New York prominent among them, and preservation doesn’t

always win.

And just as some concerned citizens felt

the need of an organization focused exclusively on Greenwich Village, more of

these good folk have joined together to maintain city parks: the Central Park

Conservancy, the Brooklyn Bridge Park Conservancy, the Battery Conservancy, the

Gracie Mansion Conservancy, the Staten Island Greenbelt Conservancy, the

Jackson Square Alliance, the Washington Square Park Conservancy, and many

more. Rare indeed is the park or

historical site in this city that doesn’t have a clutch of do-gooders organized

in a nonprofit to care for it. Not that

the Real Estate Board of New York, for all its protests and complaints, is

suffering; to judge by the current real estate boom, it’s doing just fine (see

post #178). And NYU isn’t about to

disappear. But grandiose projects like

the ones that Robert Moses sponsored are probably a thing of the past. In the constant battle between the old and

the new, the old appears to be holding its own.

History buff that I am, I’m glad.

Tax breaks for the lucky: According to a magazine I was leafing through

in a doctor’s office recently, various states offer tax exemptions to select

citizens or on certain items. For

instance:

· Pumpkins, as long as you promise to eat them

(Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Iowa).

· Circus tickets, but not trips to a haunted house (New

York).

· Adult diapers (Connecticut).

· Fortune tellers (Louisiana).

· Citizens over 100 (New Mexico).

Not having verified this

information, I would welcome comments or corrections. Also, information about additional

interesting tax breaks.

Improve your mind and body: The same magazine also listed a host of self-improvement

courses offered at various sites throughout the country. For example:

· Alligator wrestling.

· Essential witchcraft.

· Trapeze skills.

· Cannabis cultivation.

· Alchemy (ability to turn base metals into gold not

guaranteed).

Regrettably, I can’t supply

the addresses, but diligent online research will give you all you need to know.

Coming soon: Cast Iron and Terra Cotta: Adventures on 11th

Street.

©

2015 Clifford Browder

No comments:

Post a Comment