The West Village, the Manhattan

neighborhood where I live, has many old buildings that tell a tale. Let’s have a look at some of them.

The Northern Dispensary, a triangular

brick building at 165 Waverly Place, stands on a triangular plot formed by the

intersection of three streets: Waverly Place, Christopher Street, and Grove

Street. A three-story plain brick

building in the heart of Greenwich Village, a desirable high-rent district

where town houses sell for as much as $11.5 million, it stands there with a

sign proclaiming its name, vacant but not abandoned: a puzzlement. I have often passed it and wondered why, for

at least twenty years, it remains empty.

There is, of course, a story.

|

| Beyond My Ken |

The Northern Dispensary was built at the

northern edge of the city in 1831 as the city’s second clinic for the poor and

infirm and served as such for many years.

Edgar Allen Poe, who lived nearby and squandered what little money he

had on liquor, is said to have stopped in there with a head cold. As the city spread northward, the dispensary

staff were kept busy, writing twenty thousand prescriptions in 1886. By the twentieth century, with the appearance

of more hospitals, the number of patients diminished, and by the 1960s, when I

first became aware of the Dispensary, it was functioning as a dental clinic only. In the 1960s, fearing infection, it refused

service to an HIV patient, got sued, and was fined thousands of

dollars. Struggling financially, in 1989

it finally shut down. It was then

acquired by the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of New York, which sold it for

$760,000 in 1998.

The new owner, William Gottlieb, had a

fortune in New York City real estate but drove about in a beat-up old station

wagon, sloppily dressed and often unshaven, and carried his papers about in a

shopping bag. If you saw him on the

street, you’d take him for a bum. It was

his custom to buy buildings – small lots in the West Village, the Meatpacking District, and Chelsea – and sit on them for years. Sometimes he kept old buildings from being

destroyed; sometimes he let them deteriorate.

Under his ownership the Northern Dispensary deteriorated, its paint

chipped, its windows broken. Gottlieb

died in 1999, and today his nephew is trying to patch the building up; the roof

is being repaired, the interior cleaned up.

The nephew is also trying to decipher the complicated deed restrictions,

which require that the building be used to serve the poor, and ban “any obscene

performances on the premises or any obscene or pornographic purposes,” and also

prohibit abortions. What will finally

become of the building remains in doubt.

Meanwhile it still sits there, a bit forlorn.

A West Village site that is anything but

forlorn is Julius’s, a ground-floor bar in a plain, stucco-fronted building at

the corner of West 10th Street and Waverly Place, with a long bar

with a brass foot rail, and big windows facing on the street. When I first came to New York in the early

1950s, a friend described it as “Princeton on a weekend.” And when I stuck my nose in there, it did

seem to be a collegiate hangout, mostly young men, but not a gay bar. Artists too hung out there, meeting to chat

over a beer and burger.

|

| Julius's today. The third floor facing on Waverly was added in the late nineteenth century.Americasroof |

What distinguished Julius’s was its

ceiling covered with many years’ accumulation of cobwebs and dust, the sawdust

on the floor, and management’s determination not to let it become a gay bar,

even though gay men were infiltrating it discreetly. Unlike the gay bars of the time,

Julius’s wasn’t run by the mafia, and it

wasn’t paying off the police. A gatekeeper

monitored the percentage of men to women, and if he deemed the number of males

too high, he would only admit men in the company of women. And inside there was a great effort to keep

gay men from cruising each other, or at least cruising each other in a way that

was obvious.

But Julius’s, which today claims to be one

of the oldest bars in Manhattan, has gone through many phases. Built in 1826 as a two-and-a-half-story Federal-style house, for

years it housed a ground-floor grocery with the owner living on the floor

above. Then in 1864 it became a bar and

continued as such for many years until Prohibition was enacted in 1919. With its façade now stuccoed over, during the

1920s it was a speakeasy named Seven Doors, and with the repeal of Prohibition

it took the name of Julius’s, though no one knows quite why. In the 1930s and 1940s it was patronized by

horse-racing and prize-fighting fans, but also by jazz and literary people, a

period commemorated in yellowing photos and framed newspaper clippings on the

wall behind the bar.

Also drifting into the place were gay men

who lived in the neighborhood, but this was the “Princeton on a weekend” period

and the bar resisted becoming a gay bar at first. But by the 1960s, adhering to the time-tested

principle “If you can’t lick ’em, join ’em,” Julius’s became a full-fledged gay

bar. In 1966 three Mattachine Society

activists announced themselves as homosexuals and asked to be served. By prior arrangement with the management,

they were denied service, so as to challenge the New York State Liquor

Authority’s regulation prohibiting bars and restaurants from serving

homosexuals, who were labeled “disorderly.”

The Authority then denied authorizing such a prohibition, the city’s

Human Rights Commission investigated, and the courts finally ruled that gay

people had a right to peacefully assemble.

And today?

The ceiling cobwebs and sawdust are long since gone, but Julius’s still

functions as a gay bar, albeit a quiet, toned-down one. A friend of mine visited it recently and

found three distinct groups imbibing there: older gay men who were cruising

discreetly; older straight women, gay-friendly, whose presence inhibited the

men just a bit; and, arriving later, a band of “hunky” twenty- and

thirty-somethings, all good-looking, who seemed to be bar-hopping. Still a pleasant place, it would seem, and

still a quiet neighborhood bar.

The Judson Memorial Church, on the south

side of Washington Square Park, is another Village structure with a lot of

history. It was the dream of Edward

Judson, a Baptist minister living in the neighborhood, who got funding from fellow

Baptist John D. Rockefeller, Sr., the ruthless oil tycoon turned philanthropist. Built in 1892 in the Romanesque Revival style

and flanked by an Italian-style tower, the church is considered an

architectural masterpiece from the firm of the renowned architect (and future

murder victim) Stanford White, though to my eye it looms massively and oddly in

a neighborhood where Greek Revival

houses (of whom a few survive) once lined three sides of the park.

|

| Beyond My Ken |

The sober interior (Baptists embrace

sobriety) was adorned with marble relief sculpture in the baptistery based on a

design by Augustus Saint-Gaudens, and stained-glass windows by John La Farge in

the sanctuary. The windows were added

over the years as funds became available, and in contrast to the windows of the

great Gothic cathedrals of France, which tell saintly stories, many of the

Judson’s windows honor family members of the donors who made them

possible. (Well, funding is always hard

to get.)

Edward Judson, the founder and first

minister, named the church for his long-deceased father, who had been a Baptist

missionary in Burma. Eager to do

community outreach in an area with a strange mix of residents – affluent WASPS

on the lower reaches of Fifth Avenue, and Italian immigrants in tenements just

south of the park – Judson and his parishioners sponsored cooking and sewing

classes, a health facility, and employment services, and so began a tradition

of social activism that continued well into the twentieth century. Though the congregation was shrinking, during

the Great Depression of the 1930s the church at times let homeless men sleep in

the pews. Services were still

conventional in the 1950s, when my friend John and his friend April, a force of

nature celebrated long ago in this blog, joined the choir of eight, he

with an acceptable tenor voice, and April with a deplorable soprano. (Being a force of nature doesn’t guarantee

good singing.) A small choir, a small

congregation.

Then in 1957 Dr. Howard Moody became the

senior minister with a determination to shake things up and get the church

involved in local politics and culture.

With the backing of the church board, he and his assistants gave up

their clerical garb, removed crosses and pews from the church, and converted

the sanctuary into a stage. Wild things

followed, and I was a witness to some of them, if not necessarily in the church

itself, at least with the church’s backing.

For instance:

· In Circles, 1967, a plotless, shapeless musical with ten singers

and a piano, based on an enigmatic 1920 text by Gertrude Stein (all of whose

texts are enigmatic), a curious hodgepodge of words that the music -- a mix of ragtime,

tango, waltz, love song, lullaby, barbershop quartet, spiritual, and what have

you – made joyous, exuberant, and entertaining.

Most memorable moment: the pianist, a little bald gnome of a man, kisses

at length the most beautiful young woman in the cast – a beauty-and-the-beast

moment that chilled me to the quick.

· Peace, 1969, a loose adaptation of Aristophanes’ play of the

same name, which celebrated an imaginary peace between Athens and Sparta, ending

the Peloponnesian War. This production came during the Vietnam War and the vehement movement trying to end it. Another hodgepodge, with

Aristophanes turned into a minstrel show.

Most memorable moment: Peace, Prosperity, and Abundance, long imprisoned

by War, are liberated. Peace, a

remarkably beautiful, slim young blond woman, slowly raises her arms to the

audience in a gesture of welcome and radiantly smiling acceptance. Prosperity and Abundance do the same,

Abundance being another attractive young woman, dark-haired, appropriately

fleshy and abundant.

· The Journey

of Snow White, 1971, a musical

reinterpretation of the Snow White story where Snow White is sought out not by

Prince Charming but by three suitors – an opera singer, a singing cowboy, and a

rock star reminiscent of Elvis Presley – who fail to rescue her. In the end she is rescued by the Queen’s

Mirror, who decides he wants to become human.

Most memorable moment: when Snow White escapes into the forest and finds

refuge among the woodland creatures (a cast of scores of volunteers), the seven

dwarfs come marching in, led by a roly-poly girl who you immediately knew had to be a dwarf.

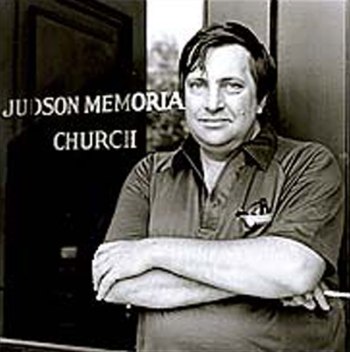

Who or what was behind these bold, wild,

exciting, unsettling, sprawling, often irreverent, and hugely creative

events? The answer is simple: Al

Carmines, assistant minister of the Judson Memorial Church. Virginia-born and musical from an early age, and

a graduate of the Union Theological Seminary in New York City, Carmines was

hired by Howard Moody in 1961 to found a theater in the church’s sanctuary and

put a little zip into the services and cultural outreach. A creative and eclectic composer and bisexual

to boot, Carmines founded the Judson Poets’ Theater, a major force in the

burgeoning Off Off Broadway movement, which challenged the conformity and

commercialization of Broadway and Off Broadway.

For inspiration he drew on Gertrude Stein, W.C. Fields, Aristophanes, the

Bible, Winnie the Pooh, history, fairy tales, and gay life; his music was

influenced by every form of pop music imaginable, with a bit of opera and

operetta thrown in. And all of this on a

minimal budget with unpaid volunteer performers.

A tall, husky, full-faced man who liked

gin and cigars, Carmines onstage was described by New York Times theater critic Clive Barnes as “crouched at his

piano like a benevolent tiger, seeming cherubic enough yet with a face that

sometimes looks like the darker side of the moon.” Carmines had a Puckish wit, no small dose of

irreverence, and liked to shock. During

his productions four-letter words and nudity invaded the church’s sanctuary, to

the horror of a few and the delight of many. The Reverend Al could also act and sing, and somehow found time to conduct services,

give sermons where God was rarely mentioned, and perform marriages as a man of

the cloth. If photos show a rather

fleshy man with a hint of self-indulgence, it hardly matters; he did wonders –

innovative, often shocking wonders – with the full blessing of the church’s

congregation. The average age of

that congregation? Twenty-eight. Which explains a lot.

A tall, husky, full-faced man who liked

gin and cigars, Carmines onstage was described by New York Times theater critic Clive Barnes as “crouched at his

piano like a benevolent tiger, seeming cherubic enough yet with a face that

sometimes looks like the darker side of the moon.” Carmines had a Puckish wit, no small dose of

irreverence, and liked to shock. During

his productions four-letter words and nudity invaded the church’s sanctuary, to

the horror of a few and the delight of many. The Reverend Al could also act and sing, and somehow found time to conduct services,

give sermons where God was rarely mentioned, and perform marriages as a man of

the cloth. If photos show a rather

fleshy man with a hint of self-indulgence, it hardly matters; he did wonders –

innovative, often shocking wonders – with the full blessing of the church’s

congregation. The average age of

that congregation? Twenty-eight. Which explains a lot.

In 1973 the Judson presented Carmines’s

musical The Faggot, which consisted

of vignettes of gay life and used the word “faggot” to describe anyone living

outside society’s concept of “normal.”

Carmines himself appeared as Oscar Wilde, though some felt his writing

couldn’t match Wilde’s in wit. The

musical got positive reviews, but the gay community criticized its

focus on the loneliness and emptiness of gay life. It was Carmines’s last notable production.

I may have seen In Circles after it moved to the Cherry Lane Theater, but wherever

it was, I was so taken with it that I went back to see it again – for me, an

almost unheard-of venture. Worse still,

it so inspired me that I began writing a dramatic hodgepodge of my own, a

plotless mix of monologues, dialogues, poetic effusions, non sequiturs, one liners, and fractured French in which the

six characters confronted one another in shifting alliances: male vs. female,

older vs. younger, conservative vs. progressive. Happily, nothing ever came of it and the script has

long since vanished. It was joyous

enough but of its moment; it wouldn’t fly today. But In

Circles won an Obie Award from the Village

Voice, one of five that Carmines would receive. (The mainstream press in those days ignored the downtown Off Off Broadway scene, but the Voice reported it with enthusiasm.)

The radiantly beautiful young woman playing

Peace was Arlene Rothstein, an actress, dancer, and choreographer who often

appeared in Carmines’s productions. She

may have been the young woman in In

Circles who was kissed by the pianist.

Only in researching this post did I learn that she died later at age 37

of meningitis, a sad ending to a promising career.

Mortality stalked the Reverend Al as well. In 1977 his creative career was interrupted

by a cerebral aneurysm that required a lengthy operation followed by months of

therapy, and he never quite recovered the musical flair and inventiveness that

had characterized his career up till then. Crippling headaches forced him to resign from his post

at Judson in 1981, until they were cured by a second surgery in 1985. In his later years he turned more toward religion, and a Bible study group that he held in

his apartment evolved over time into the Rauschenbusch Memorial United Church of Christ

at 422 West 57th Street, with him as pastor. The opening night for the congregation

involved hymn, Bible readings, and a soft-shoe routine. Carmines died in Saint Vincent’s Hospital in

2005 at age 69.

Another memorable event of those years was

Dames at Sea, or Golddiggers Afloat, a

light and frothy musical revue that opened at the Caffe Cino on Cornelia Street

in 1966, a takeoff on the lavish Busby Berkeley musical films of the 1930s, but

doing it on a tiny stage with a cast of six.

Memorable moment: Mona, the self-centered star of a Broadway musical in

rehearsal, starts singing “That Mister Man of Mine,” a song that is new to her;

after a note or two she cavalierly tosses the music away and continues. Another memorable moment: Mona performs with

a chorus behind her, the chorus consisting of a single showgirl. Later in the revue, even though the cast, having been

expelled from their theater, are rehearsing on a ship in dry dock, Mona gets

seasick, so that Ruby, an aspiring young singer from Utah, steps in and becomes

a star. The whole production was a spoof

of Hollywood done in miniature, charming from beginning to end. I saw it twice, and the second time around it

had lost nothing of its charm. But when,

being successful, it moved to a larger stage, I doubt if it retained that

charm; it needed to be done small-scale. Yet it endured and in 2014 made its way to Broadway.

The founder and guiding spirit of the

Caffe Cino was Joe Cino, who with friends founded it in 1958. Born in Buffalo to a family of working-class

Sicilian immigrants, he had discovered he was gay and at the age of sixteen escaped

to New York, where his hopes to be a dancer were defeated by his short, plump

frame. Renting a storefront at 31 Cornelia

Street, where the Italian landlady rented to him because he was Sicilian, he

put in some mismatched tables and chairs, a big coffee machine on a counter in

back, and served pastries and snacks.

|

| The Caffe Cino in 1965. |

Joe Cino first meant his cafe to be a place where

his friends could hang out, but soon there were poetry readings, then readings

of plays, and then amateurish staged productions. When young unknowns brought in their works,

the Caffe Cino began performing them on a tiny improvised stage and so turned into

an Off Off Broadway theater playing to a minimal audience – sometimes as few as

ten or even one -- that slowly grew over time.

The sets were simple, and for power John Torrey, Cino’s electrician lover,

ran cables out to a streetlamp and stole power from the city grid. There was no admission fee; Cino passed the

hat. With no cabaret or theater license,

and an audience that on some nights filled the place beyond capacity, the Cino

was repeatedly inspected by the police and building and fire inspectors but

was never shut down, perhaps because Joe Cino knew which palms to grace with

money.

The quality of the plays performed at the

Cino ranged from deplorable to weirdly brilliant, but theatrical history was

made with the 1964 production of Lanford Wilson’s The Madness of Lady Bright, a monologue by an aging drag queen who

gradually descends into madness. Rarely,

if ever, had any New York theater presented such an openly gay character, but

Off Off Broadway was ready for it, and audiences flocked. My partner Bob, then in his twenties, saw it

and was mightily impressed, and through a mutual friend met the actor, Neil

Flanagan, who won an Obie for his performance.

|

| John Torrey (left) and Joe Cino in 1962. |

In March 1965 a fire gutted the Caffe

Cino, reportedly because of leaking gas, though Joe’s friends thought it was

started by John Torrey in a jealous rage.

With help from benefits staged by the Village theater world, the Cino

reopened in May, but its world of regulars was repeatedly shocked and saddened

as friends and acquaintances succumbed to heavy drugs, which one survivor later

described as “the dark underbelly of Off-Off-Broadway theater.” One, a dancer hooked on amphetamines, danced

a nude dance in a friend’s apartment and then leaped gracefully out a window to

his death. And when, in January 1967,

John Torrey was electrocuted, supposedly by accident, many suspected

suicide. By then Joe himself was on

amphetamines and at news of Torrey’s death fell into deep depression. On March 30 of that year friends found him on

the floor of the Cino, bleeding from self-inflicted knife wounds; he died in

Saint Vincent’s Hospital on April 2. A

year later the Caffe Cino closed.

Did I ever see a performance at the Caffe Cino? I have a dim memory of a play by an unknown author performed on an improvised stage in the middle of a small theater or cafe; probably it was the Caffe Cino. And since I don't recall buying a ticket, Joe Cino probably passed the hat. The play wasn't bad and at one point the leading character asked the audience what he should do, at which point a young girl sitting near the stage declared, "You don't have to do anything you don't want to!" -- a response, quite in keeping with the times, that drew applause.

Joe Cino’s sad ending is a reminder that

the wild creativity of the 1960s came at a price. Many of the participants were heavy into

liquor and drugs and failed to sustain themselves as artists. Inspiration raged, along with a willingness

to try anything, but in the long run art needs discipline too, and discipline

was the last thing that early Off Off Broadway embraced. The writers and producers were amateurs, and

it showed. For every theatrical gem that

Off Off Broadway produced, there were a hundred botches and flops. The few samples I saw of Ellen Stewart’s La

MaMa – another pioneering Off Off Broadway theater – struck me as amateurish,

unfocused, inept. As for pioneering

works in gay theater, neither The Madness

of Lady Bright nor The Faggot presented

gay life in a positive light; to be gay was to be vulnerable, wounded, and

sad.

Nor was this image altered when Mart

Crowley’s play The Boys in the Band

opened uptown in an Off Broadway theater in 1968 and was similarly hailed as a

breakthrough for promoting knowledge and tolerance of gay life. Perhaps it did, but as the story unfolds, the

characters become bitter and vicious, and capable as well of self-loathing, as

seen in the play’s most memorable line: “You show me a happy homosexual, and

I’ll show you a gay corpse.” I and my friends were glad to see gay life at last treated openly uptown, but we had mixed feelings about how the play presented it. There was

little in Crowley's play to advance the cause of gay pride, which exploded onto the scene with the Stonewall riots of 1969.

The wild theatrical happenings of those

days, many of them in the West Village, are today a treasured memory for the

survivors. But not all the participants

survived.

Coming soon: My Walks in New York: arcades, diamond

districts, Norman Vincent Peale and Minnie Mouse, and the new Whitney.

©

2015 Clifford Browder

No comments:

Post a Comment