BROWDERBOOKS

My historical novel Forbidden Brownstones has received two more good reviews.

No matter what journey you’re looking to undertake, this author provides love, drama, mystery, action, death, prejudice, and unforgettable emotion. — Editorial review for Reader Views by Amy Lignor.

A must read…. I could feel the movement, the jazz of the black culture where characters swayed with the rhythm of life after years of slavery facing adversity no white person in the book could ever understand or even thought to ask. — Five-star editorial review for Reedsy Discovery by Karina Holosko.

KILL

Kill: the word in English, a monosyllable, has a directness to it that no other language I know of can match. It is blunt, keen, harsh. Shakespeare is aware of this when, in Act 4, Scene 6, he has Lear say

And when I have stol'n upon these sons-in-law,

Then, kill, kill, kill, kill, kill!

But we also use it more gently.

· “He made a killing in the market.”

· “We’re just killing time.”

· Fred Trump to his son Donald: “Be a killer.”

· “You kill me.”

In none of these is it a matter of depriving someone or something of life. What the last one means depends on the context. It is very twentieth-century, very American; I heard it in the movies. It means “You’re overdoing it, but I’m not fooled.”

Have I ever seen a killer? Yes, but not a human. At the Aquarium at Coney Island I have seen a shark swimming in a tank. His supple, streamlined body, his eye, his jaw with jagged, inward-curved teeth – all these features suggest a living machine designed to hunt and kill. And the more a victim struggles to escape, the more those teeth cut into him, rendering escape impossible.

|

| Vahe Martirosyan |

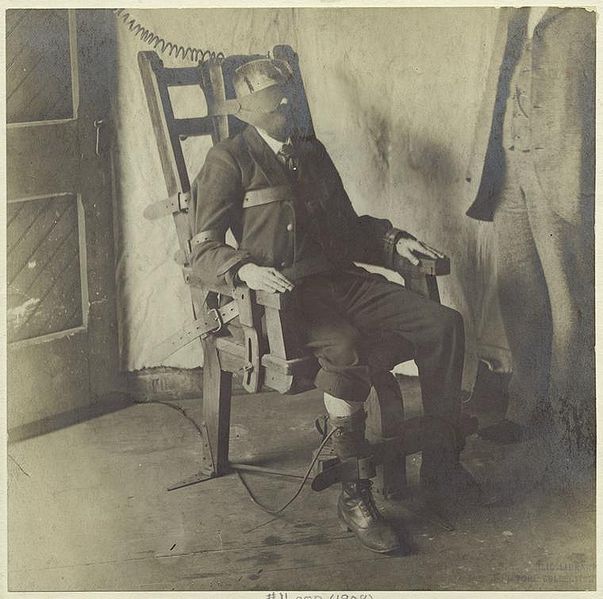

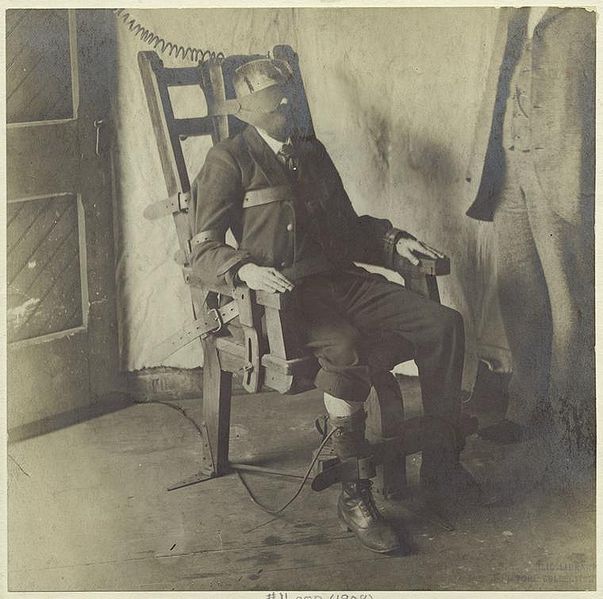

Humans have tried to create machines for killing, so they don’t have the grim responsibility of hacking off a head, or firing a gun, or pulling a lever that sends the doomed man’s body plunging into space. The electric chair, once so highly esteemed in progress-addicted America, has proven untrustworthy, as evidenced by gasps and twitchings of the victim.

|

| Man in an electric chair, 1908. |

But the French came up with a far more efficient device, evidently invented by a surgeon named Antoine Louis, but promoted by a deputy in the National Assembly, Dr. Joseph Ignace Guillotin. A child of the Enlightenment, Guillotin was shocked by the thought of the condemned being broken on the wheel, or drawn and quartered, or burned at the stake, or drowned. He hoped that a more humane method of execution would ultimately lead to abolition of the death penalty. On October 10, 1789 – three months after the storming of the Bastille – he addressed the reform-minded Assembly, declaring, “With my machine I take off your head in the twinkling of an eye, and you never feel it.” He and his machine were mocked at first, but on June 3, 1791, the Assembly made the guillotine the only means of legal criminal execution. Workers shunned the job of making it, until a German harpsichord maker agreed, on condition of anonymity, to manufacture it. It was tested on animals and human corpses, perfected, and then busily employed in killing the Revolution’s innumerable victims, the king and queen among them, followed by the fanatical Robespierre.

|

| Showing Louis XVI's head to the crowd. A German engraving, 1793. |

Legend has it that Dr. Guillotin not only gave his name to the machine, but died by it as well. No, he died in 1814 of natural causes at age 75. Embarrassed by their connection to it, his family asked the government to change the machine’s name, and when the government refused, they changed their name instead. But the guillotine was the standard form of execution in France until the death penalty was abolished in 1981. And Hitler loved it; during his rule, thousands died by it.

If the guillotine is so painless and efficient, why hasn’t it been adopted here? Because, I think, it’s messy. Heads roll, blood flows, the body is mutilated. With hanging, at least the corpse is intact. We like neat, bloodless executions, even if the victim gasps and twitches. A nasty business, no matter how you look at it.

Dr. Guillotin wanted executions to be private, but the Revolution made them public, so the populace could cheer when the executioner showed them the severed head of the king or some other victim of significance. The tricoteuses of the executions, those fiercely knitting Madame Defarges, have themselves become legendary.

Today, in America, killing by the state is as controversial as ever. Some states have banished the death penalty; others, like Texas, glory in it. And just as controversial is abortion: some states ban it, some do not. That these issues are fiercely debated is understandable: human life is at stake. And for me, they aren't easy. I marvel at those who come down on one side or the other without hesitation. In any discussion of the death penalty or abortion, I am haunted by the thought of kill.

© 2021 Clifford Browder

Well, on this one issue I certainly "come down on one side... without hesitation": The death penalty is horrible, barbaric and wrong.

ReplyDeleteIf you marvel at me for it, so be it.