She's young, blond, and sexy, and promises marvels. Though Russian-born, in this country Alinka Rutkowska has adopted all the ways of enterprising capitalism and made herself a fortune. She's all over the Internet, promising to make authors the same kind of fortune that she has made for herself. Want to land on the USA Today bestseller list? She'll show you how. Stymied in your book marketing attempts? She'll help you attain remarkable success ... for a price. Two of her many books, bestsellers all: How I Sold 80,000 Books, Write and Grow Rich -- yours for only $2.99.

Have I had dealings with her? Yes, in a limited way. For a fee, I enrolled in her LibraryBub program, which supposedly made my first self-published title available to libraries, though I saw no notable increase in sales. Will I do it again? Yes, though at her bargain price, without expensive frills. So what do I expect? More exposure, a few sales, nothing more.

Why haven't I banished her to oblivion, as I have so many exploiters of aspiring and gullible Indie authors? Well, have a look at her online. She makes business sexy. Maybe it's her long blond hair. Or her enticing smile. I like her, she's fun. If nothing else, I keep her around for laughs.

A note on Goldman Sachs

On an errand recently (properly masked), I went to my local independent pharmacy, Grove Drugs, and in the window I saw a conglomeration of objects that I recognized: old bottles of every size and shape, mortars and pestles, scales for weighing, dusty old books, and a massive volume, its pages open to reveal careful scribblings now indecipherable. I recalled seeing an almost identical display there three years ago, reported in post #309, which I am reproducing here, abridged. It takes us back to an earlier age when customers got individual remedies for their ailments.

Belladonna, which appears in the Grove Drugs window display, figures often in history and legend. It is said that Livia, the wife of the Roman emperor Augustus, used it to do away with her husband, so that Tiberius, her son by another marriage, could succeed him. And in folklore, witches used a mixture of belladonna, opium, and other poisons to help them fly to conclaves of witches called sabbaths, where participants did naughty things, danced wildly, and kissed the devil’s behind. The shiny black berries have been called “murderer’s berries,” “sorcerer’s berries,” and “devil’s berries.”

Belladonna, which appears in the Grove Drugs window display, figures often in history and legend. It is said that Livia, the wife of the Roman emperor Augustus, used it to do away with her husband, so that Tiberius, her son by another marriage, could succeed him. And in folklore, witches used a mixture of belladonna, opium, and other poisons to help them fly to conclaves of witches called sabbaths, where participants did naughty things, danced wildly, and kissed the devil’s behind. The shiny black berries have been called “murderer’s berries,” “sorcerer’s berries,” and “devil’s berries.”

A note on Goldman Sachs

Followers of this blog know the love I have for Goldman Sachs,

which has been described as a vampire squid sucking profits out of everything it touches. Though I disapprove of the outfit, whose former execs have a way of infiltrating presidential cabinets, I can't help but marvel at its ability to feel out profits and suck them up. But Public Citizen has announced a signal victory: it has nudged the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) into issuing an order rejecting Goldman Sachs's denial of affiliation with a private equity company called Goldman Sachs Renewable Power. Investigating the names of this company's board members, Pub Cit found that the same three served on the boards of some 70 shell companies with ties to Goldman Sachs. After more digging, Pub Cit learned that the omnipresent trio work for companies based in the Cayman Islands that offer "directors for hire" to private equity shell companies for Wall Street. So for once, the vampire squid's behind-the-scenes attempt to control an allegedly independent shell company has failed. But this, I suspect, is just the tip of the iceberg. The vampire squid's tentacles reach everywhere and are rarely detected, as happened on this occasion, thanks to Public Citizen. (For more on the vampire squid, see post #340 and scroll down to "Goldman Sachs: The Vampire Squid Thrives On.")

APOTHECARIES:

COCAINE, ARSENIC, AND OPIUM,

AND ALL OF IT JUST FOR YOU

On an errand recently (properly masked), I went to my local independent pharmacy, Grove Drugs, and in the window I saw a conglomeration of objects that I recognized: old bottles of every size and shape, mortars and pestles, scales for weighing, dusty old books, and a massive volume, its pages open to reveal careful scribblings now indecipherable. I recalled seeing an almost identical display there three years ago, reported in post #309, which I am reproducing here, abridged. It takes us back to an earlier age when customers got individual remedies for their ailments.

CARDAMUM

CAMPHOR

AMMONIUM CHLORIDE

ZINC OXIDE

ALUM

RHUBARB AND SODA MIXTURE

BELLADONNA

A row of time-worn books, one labeled Elements of Chemistry. Two thick, massive volumes brown with age, open to pages with scores of prescriptions affixed, scribbled in a near-indecipherable hand, their dates not visible, but probably from the early twentieth century. The whole display fascinating, puzzling, reeking with history and age.

|

| Apothecary jars |

Such is the current window display of Grove Drugs, but a couple of blocks from my apartment. One of the few independent pharmacies left in the West Village, where chain stores dominate, Grove typically provides window displays of unusual interest, and this one fascinates. When I asked inside about the source of the earlier display, I was told that these objects had been found in the basement of the Avignone Chemists at Bleecker Street and Sixth Avenue, now closed, whose antecedents had gone back a century or more. Discovered during a renovation in 2007, these relics of the past might have been discarded but were preserved. Now,

when displayed, they give us a glimpse of the pharmaceutical past, when the time-honored apothecary shop prevailed.

The profession of apothecary dates back to antiquity and differs from that of pharmacists today. Pharmacies today are well stocked with mass-produced over-the-counter products that come in standardized dosages formulated to meet the needs of the average user. But in earlier times the apothecary created medications individually for each customer, who received a product specific to his or her needs. In theory, the apothecary had some knowledge of chemistry, but at first there was scanty regulation.

|

| A Flemish apothecary shop, late 14th or early15th century. |

A 17th-century German apothecary.

Welcome Library |

The objects on display in Grove’s window hearken back to this early period when the apothecary made compounds from ingredients like those in the bottles and jars displayed, grinding them to a powder with a mortar and pestle, weighing them with scales to get just the right measure, or distilling them with the glass paraphernalia seen in the window to make a tincture, lotion, volatile oil, or perfume. The one thing typical of the old apothecary shops that the display can’t reproduce is the aroma, a strange mix of spices, perfumes, camphor, castor oil, and other soothing or astringent remedies. Mercifully absent as well from the Grove display is a jar with live leeches, since by the late nineteenth century the time-honored practice

The apothecary’s remedies were derived sometimes from folk medicine and sometimes from published compendiums. Chalk was used for heartburn, calamine for skin irritations, spearmint for stomachache, rose petals steeped in vinegar for headaches, and cinchona bark for fevers. Often serving as a physician, the apothecary applied garlic poultices to sores and wounds and rheumatic limbs. Laudanum, or opium tincture, was employed freely, with little regard to its addictiveness, to treat ulcers, bruises, and inflamed joints, and was taken internally to alleviate pain. But if some of these remedies seem fanciful, naïve, or even dangerous, others are known to work even today, as for example witch hazel for hemorrhoids.

But medicines weren’t the only products of an apothecary shop. Rose petals, jasmine, and gardenias might be distilled to create perfumes, and lavender, honey, and beeswax were compounded to create face creams to enhance the milk-white complexion desired by ladies of the nineteenth century, when the sun tan so prized today marked one as a market woman or farmer’s wife, lower-caste females who had to work outdoors for a living. (The prime defense against the sun was the parasol, without which no Victorian lady ventured outdoors.) A fragrant pomade for the hair was made of soft beef fat, essence of violets, jasmine, and oil of bergamot, and cosmetic gloves rubbed on the inside with spermaceti, balsam of Peru, and oil of nutmeg and cassia were worn by ladies in bed at night, to soften and bleach the hands, and to prevent chapped hands and chilblains.

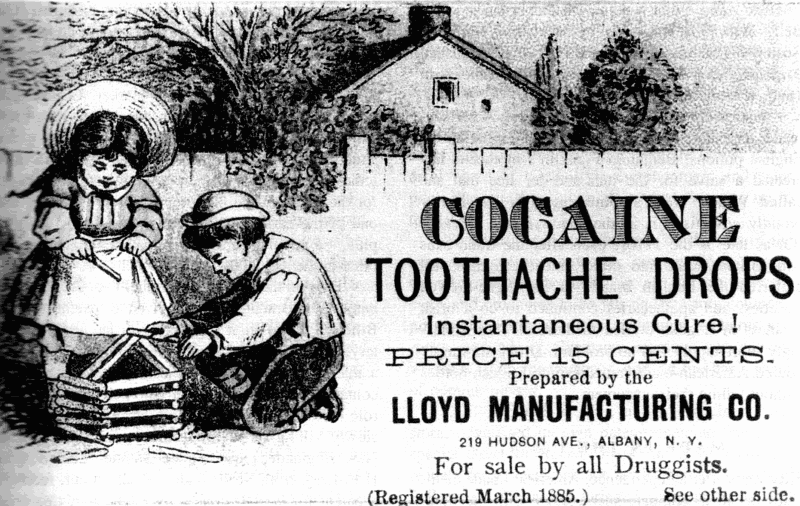

But there were risks. Face powders might contain arsenic; belladonna, a known poison, was used to widen the pupils of the eyes; and bleaching agents included ammonia, quicksilver, spirits of turpentine, and tar. All of which suggests a lousy grasp of basic chemistry. And in the flavored syrups and sodas devised to mask the unpleasant medicinal taste of prescriptions, two common ingredients were cocaine and alcohol, which must have lifted the users to pinnacles of bliss.

Marketed especially for children.

|

Also available in an apothecary shop

were cooking spices, candles, soap, salad oil, toothbrushes, combs, cigars, and tobacco, so that it in some ways resembled the small-town general store of the time. And in the eighteenth century American apothecaries even made house calls, trained apprentices, performed surgery, and acted as male midwives.

Belladonna, which appears in the Grove Drugs window display, figures often in history and legend. It is said that Livia, the wife of the Roman emperor Augustus, used it to do away with her husband, so that Tiberius, her son by another marriage, could succeed him. And in folklore, witches used a mixture of belladonna, opium, and other poisons to help them fly to conclaves of witches called sabbaths, where participants did naughty things, danced wildly, and kissed the devil’s behind. The shiny black berries have been called “murderer’s berries,” “sorcerer’s berries,” and “devil’s berries.”

Belladonna, which appears in the Grove Drugs window display, figures often in history and legend. It is said that Livia, the wife of the Roman emperor Augustus, used it to do away with her husband, so that Tiberius, her son by another marriage, could succeed him. And in folklore, witches used a mixture of belladonna, opium, and other poisons to help them fly to conclaves of witches called sabbaths, where participants did naughty things, danced wildly, and kissed the devil’s behind. The shiny black berries have been called “murderer’s berries,” “sorcerer’s berries,” and “devil’s berries.”

All in all, not a plant to mess with, although a staple in most apothecary shops. And if you think you’ve never gone near it, think again, for if you’ve ever had your eyes dilated, belladonna is in the eye drops. And the name is intriguing: belladonna, the beautiful lady who poisons. Which brings us back to the Empress Livia; maybe she did do the old boy in.

Given their lack of formal training and use of questionable ingredients, one may ask why, for centuries, apothecaries attracted a steady clientele. Because the only alternative was the medical profession, and prior to the nineteenth century they "cured" you by bleeding you or purging you, and in so doing sent many a patient to the grave. Mixing a medication meant specifically for you, apothecaries looked pretty good by comparison, probably killed fewer patients, and at times even managed a cure.

Given their lack of formal training and use of questionable ingredients, one may ask why, for centuries, apothecaries attracted a steady clientele. Because the only alternative was the medical profession, and prior to the nineteenth century they "cured" you by bleeding you or purging you, and in so doing sent many a patient to the grave. Mixing a medication meant specifically for you, apothecaries looked pretty good by comparison, probably killed fewer patients, and at times even managed a cure.

Gradually, the professions of apothecary and pharmacist -- never quite distinct – became more organized, and then more regulated. In the nineteenth century patent medicines (which were not patented) became big business, thanks to blatant advertising, but their mislabeling of ingredients and their extravagant claims finally resulted in the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906. This and subsequent legislation probably benefited apothecaries, since mass-produced patent medicines competed with their products.

|

| Collier's attacks the patent medicine industry. |

As late as the 1930s and 1940s, apothecaries still compounded some 60% of all U.S. medications. In the years following World War II, however, the growth of commercial drug manufacturers signaled the decline of the medicine-compounding apothecary. In 1951 new federal legislation introduced doctor-only legal status for most medicines, and from then on the modern pharmacist prevailed, dispensing manufactured drugs.

By the 1980s large chain drugstores had come to dominate the pharmaceutical sales market, rendering the survival of the independent neighborhood pharmacy precarious. But in a final twist, the word “apothecary,” meaning a place of business rather than a medicine compounder, has become “hip” and “in,” appearing in names of businesses having nothing to do with medicines. As for a business that does indeed deal in medicines, a longtime pharmacy in the West Village calls itself the Village Apothecary. The word "apothecary" expresses a nostalgia for experience free from technology and characterized by creativity and a personal touch, a longing for Old World tradition and gentility. In other words, it's charmingly quaint. And as one observer has commented, “apothecary” is fun to say.

Coming soon: New Yorkers and the Virus: An Outdoor Baby Grand, a Naked Jesus, Free Haircuts, Mopeds, Bikes.

© 2020 Clifford Browder

This comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

ReplyDelete