BROWDERBOOKS

My latest book, the fourth title in my Metropolis series of historical novels set in nineteenth-century New York.

A story of the strangest friendship that ever was: a dapper young bank thief and the detective hired by the banks to apprehend him.

Reviews

"What a remarkable novel! Clifford Browder's The Eye That Never Sleeps is an exciting cat and mouse game between a detective and a bank thief that is simultaneously so much more. A lively, earthy stylist with a penchant for using just the right word, Browder captures a city pullulating with energy. I loved this book right down to its satisfying, poignant ending." -- Five-star Amazon review by Michael P. Hartnett.

"New York City in the mid-nineteenth century is described in vivid detail. Both the decadent activities of the wealthy and the struggles of the common working class portray the life of the city." -- Four-star NetGalley review by Nancy Long.

"Fascinating!" -- Five-star NetGalley review by Jan Tangen.

For the full reviews of the above three reviewers, go here and scroll down.

"Well written, flowing with a feeling for the time and the characters." -- Reader review by Bernt Nesje.

The Eye That Never Sleeps is certain to amaze and engage not just historical mystery fans, but anyone seeking an exciting new read. -- Five-star Readers' Favorite review by K.C. Finn.

My nonfiction work Fascinating New Yorkers has been reviewed by The US Review of Books. Reviewer Gabriella Tutino says, "There's something for everyone here in this collection of profiles, and it serves as a source of inspiration for readers who love NYC." For the whole review, click on US Review.

For more about my other books, go here.

Kill

Kill: the word in English, a monosyllable, has a directness to it that no other language I know of can match. It is blunt, keen, harsh. Shakespeare is aware of this when, in

Act 4, Scene 6, he has Lear say

And when I have stol'n upon these sons-in-law,

Then, kill, kill, kill, kill, kill!

Then, kill, kill, kill, kill, kill!

But we also use it more gently.

· “He made a killing in the market.”

· “We’re just killing time.”

· Fred Trump to his son Donald: “Be a killer.”

· “You kill me.”

In none of these is it a

matter of depriving someone or something of life. What the last one means depends on the

context. It is very twentieth-century,

very American; I heard it in the movies.

It means “You’re overdoing it, but I’m not fooled.”

Have I ever seen a killer?

Yes, but not a human. At the Aquarium

at Coney Island I have seen a shark swimming in a tank. His supple, streamlined body, his eye, his jaw with jagged, inward-curved teeth – all these features suggest a

living machine designed to hunt and kill.

And the more a victim struggles to escape, the more those teeth cut into

him, rendering escape impossible.

|

| Vahe Martirosyan |

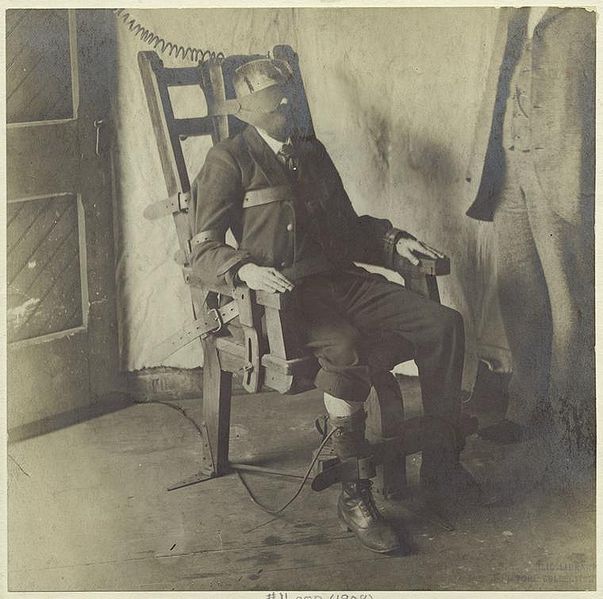

Humans have tried to create machines for killing, so they

don’t have the grim responsibility of hacking off a head, or firing a gun, or

pulling a lever that sends the doomed man’s body plunging into space. The electric chair, once so highly esteemed

in progress-addicted America, has proven untrustworthy, as evidenced by gasps

and twitchings of the victim.

|

| Man in an electric chair, 1908. |

But the

French came up with a far more efficient device, evidently invented by a

surgeon named Antoine Louis, but promoted by a deputy in the National Assembly,

Dr. Joseph Ignace Guillotin. A child of

the Enlightenment, Guillotin was shocked by the thought of the condemned being

broken on the wheel, or drawn and quartered, or burned at the stake, or

drowned. He hoped that a more humane

method of execution would ultimately lead to abolition of the death

penalty. On October 10, 1789 – three

months after the storming of the Bastille – he addressed the reform-minded Assembly, declaring,

“With my machine I take off your head in the twinkling of an eye, and you never

feel it.” He and his machine were mocked

at first, but on June 3, 1791, the Assembly made the guillotine the only means

of legal criminal execution. Workers

shunned the job of making it, until a German harpsichord maker agreed, on

condition of anonymity, to manufacture it.

It was tested on animals and human corpses, perfected, and then busily

employed in killing the Revolution’s innumerable victims, the king and queen among

them, followed by the fanatical Robespierre.

|

| Showing Louis XVI's head to the crowd. A German engraving, 1793. |

Legend has it that Dr. Guillotin not only gave his name to

the machine, but died by it as well. No,

he died in 1814 of natural causes at age 75.

Embarrassed by their connection to it, his family asked the government

to change the machine’s name, and when the government refused, they changed

their name instead. But the guillotine

was the standard form of execution in France until the death penalty was

abolished in 1981. And Hitler loved it; during

his rule, thousands died by it.

If the guillotine is so painless and efficient, why hasn’t

it been adopted here? Because, I think,

it’s messy. Heads roll, blood flows, the

body is mutilated. With hanging, at

least the corpse is intact. We like

neat, bloodless executions, even if the victim gasps and twitches. A nasty business, no matter how you look at

it.

Dr. Guillotin wanted executions to be private, but the

Revolution made them public, so the populace could cheer when the executioner

showed them the severed head of the king or some other victim of

significance. The tricoteuses of the executions, those fiercely knitting Madame

Defarges, have themselves become legendary.

There is, buried deep in many of us, a delight in watching

others being put to death. Throughout

history governments have turned executions into public events, ostensibly to

show that crime doesn’t pay, to display the fate of its challengers, those who

presume to threaten its security or that of society. In Tudor England executions were

well-attended public events, and victims pronounced what they hoped would prove

to be memorable utterances. Catherine

Howard, Henry VIII’s fifth wife, facing execution for adultery, is said to have

humiliated Henry by proclaiming, “I had rather be the wife of Culpeper than

queen of England!” Memorable indeed,

though not supported by any eyewitness account.

More likely, knowing her last words would be reported to the king, she

asked for forgiveness, hoping to protect her family. She was only 18.

In this country executions were also often public. As for lynchings, by their very nature they

were public events, and even celebrations.

Postcards often showed the dangling hanged bodies of the victims,

usually black males, with a host of smiling

white witnesses, including even women and children. One wonders at the state of mind not only of

those posing proudly near the dangling bodies, but also of those who sent the

postcards by mail. Who did they send

them to, and with what scribbled message?

One appears online, on a postcard from Waco, Texas, dated 1916: “This is

the barbecue we had last night. My

picture is to the left with a cross over it.

Your son, Joe.”

The postcards were also kept as souvenirs and in time became

collectors’ items. It is worth noting

that the Nazis never stooped to selling souvenirs of the death camps. In the U.S., by 1908 the postcards had become

so common, and to many so repugnant, that the U.S. Postmaster General banned

them from the mails. After that they

continued to be sold in antique stores whose proprietors whispered to

prospective buyers that they were available, though not on display. These souvenirs so offend me that I cannot

reproduce them here. Nor would they be

appreciated today by the residents of the communities involved, which were by

no means all in the South. These

celebratory killings occurred also in Cairo, Illinois (1909), Anadarko,

Oklahoma (1913), Duluth, Minnesota (1920), and Marion, Indiana, 1930. They are accessible online at Wikimedia Commons,

for those who want to see them. I have

seen them and received their message, and that is quite enough.

I have told elsewhere, and more than once, how my father was

a hunter and fisherman, and raised his two sons to be the same. With me, it didn’t take. Though he taught me to use a shotgun at age

16, I had no desire to kill the blackbirds that he hoped would appear overhead

in autumn fields where we patiently waited, or the occasional rabbit that

scurried away from us. And I hated the

pain in my shoulder from the recoil of the shotgun, when fired. Though in his will he left his guns to his

sons, we were quite happy to sell them.

Sad. In this regard (and others),

we were not the sons he had wanted. The

guns involved, by the way, were shotguns used for trap shooting and

hunting. He had no interest in handguns,

much less automatic weapons (unheard of in his time), and would be dismayed by

their availability today.

|

| The legendary Annie Oakley shooting a shotgun before spectators in Pinehurst, NC, date unknown. What she's shooting at isn't clear. |

So I am not a killer? Wrong. Under certain circumstances I can kill with gusto. But only the roaches that infest my apartment, in an old building whose cracks and crevices – too many to ever be filled – provide them with nesting spaces where they can rest up by day and prepare for their nocturnal forays. When, heeding the bladder imperative, I go to the bathroom at night, I surprise gangs of them in the wash basin and tub and either chase them into a waiting glue trap, or – BAM BAM BAM – pound them with the smooth cap top of an empty medicine bottle. Many escape, but not all. Still, I am not an indiscriminate killer. Roaches, yes; spiders, no. Spiders I always spare, though I may relocate them to a green plant or release them to the world outside. Any bug that kills flies and mosquitos is a friend of mine.

|

| My enemy. Robert Webster |

|

| My friend. L. Shyamal |

When to kill and when not to is a problem besetting us

all. It comes up repeatedly in regard to

abortion and the death penalty. Both

involve human life, and for this reason both of these issues perplex me. All my friends here in New York support

freedom of choice, meaning they support a woman’s right to have an

abortion. When women say that men should

not tell them what to do with their bodies, I listen and agree. But when the pro-life camp declare that life

begins at the moment of conception, I also agree, and cannot easily dismiss

their emphasis that human life is sacred, and not to be taken lightly. Which puts me in a bind

|

| Anti-abortion protest, San Francisco, 1986. Nancy Wong |

Similarly, I am troubled by the taking of life by the state through the death penalty. If life in an unborn child is sacred, why not in a convicted criminal as well, no matter how heinous the crime? And the all-too-frequent miscarriage of justice – the absence of DNA testing, the evidence never presented at trial, the subsequent recanting of witnesses – make the death penalty all the more questionable. Yet the pro-life people tend to support it, and the pro-choice people tend to oppose it. And I’m caught in the middle, open to the arguments on both sides.

|

| Anti-death penalty protest at the Governor's Mansion, Austin, Texas, 2005. Texas Moratorium Network |

And the debate rages on. In the Sunday Review section of the New York Times of June 23, a whole series of letters to the editor, responding to an article against the death penalty, present the pros and cons. A New York resident tells of serving on a jury for a murder case where there was no doubt that the accused did slit the throat of an elderly woman and let her bleed to death in front of her lifelong partner. Would the writer have voted for the death penalty, had it not been abolished in New York? Absolutely. But a pro-life practicing Catholic in Florida opposes it, convinced that it is neither a deterrent nor less costly than life imprisonment. And the others support either the one view or the other, citing cogent reasons for their stance. And there I am again, right in the middle, sympathetic to arguments both pro and con. What I don’t understand is how, when human life is involved, people can make up their mind quickly and emphatically, without hesitation. I’m wishy-washy, if you like, but keenly aware of the complexities involved. Regarding both abortion and the death penalty, the two sides have a point to make, and they make it with conviction.

Here’s a positive note to end on. From time to time I have what I call a kill

day. No, I don’t go out on the street

and start shooting; that’s not my style.

A kill day is when I leave to one side my usual practices and devote

myself to tasks that may seem negative and destructive, but are necessary and,

in their way, positive. I may make a

long-delayed decision that involves canceling some commitment – maybe a

donation to a nonprofit that no longer makes sense to me, or attending some

worthy but irrelevant affair. Above all,

I throw things out. I go to my desk,

look for clutter. A file with clippings

for a blog post I’ve decided not to write?

Out. A record of requests for

reviews from reviewers who said they would, but didn’t? Out. A

file of items pertaining to BookCon, the two-day book fair at the Javits

Center, that I’ve decided not to do again?

Out. A big cardboard folder that

I thought I might use, but haven’t?

Out. You get the idea. Far from being savagely destructive, kill

days can be a time for cleaning and clarifying, for de-cluttering your

apartment and your mind, for achieving focus.

We all should have one from time to time. They simplify, they cleanse.

Coming soon: The Fourth: how we really celebrate it. And then: AIDS.

© 2019

Clifford Browder

No comments:

Post a Comment