BROWDERBOOKS

A story of the strangest friendship that ever was: a dapper young bank thief and the detective hired by the banks to apprehend him. The latest review:

"Well written, flowing with a feeling for the time and the characters." -- Reader review by Bernt Nesje.

For two more reviews, both five stars, go here and scroll down.

This is the fourth title in my Metropolis series of historical novels set in nineteenth-century New York. Three more, and then the big one; stick around.

My latest nonfiction work, Fascinating New Yorkers, has been reviewed by The US Review of Books. Reviewer Gabriella Tutino says, "There's something for everyone here in this collection of profiles, and it serves as a source of inspiration for readers who love NYC." For the whole review, click on US Review.

For more about my other books, go here.

Gold

What do all these things have in common?

· Robber barons Jim Fisk and Jay Gould being chased down

the street by a mob of ruined speculators.

· Siegfried.

· The first Wise Man.

· A flotilla of abandoned sailing vessels in San

Francisco harbor.

· William Jennings Bryan.

· Abraham Lincoln pounding his fist on a table and

saying, “I wish every one of them had his devilish head shot off!”

· Midas.

· Medieval alchemists.

· Fort Knox.

The answer, of course, is gold. They were all concerned with it in one way or

another.

· Fisk and Gould’s attempt to corner gold in 1868

convulsed financial markets on both sides of the Atlantic. Speculators ruined in the panic tried to

assault them, causing the merry duo to high-tail it out of Wall Street and take

refuge in Fisk’s Opera House, its thick locked doors guarded by their crony

Boss Tweed’s police.

· In Wagner’s Ring

the hero Siegfried kills the dragon Fafnir and gets possession of the stolen

gold that Fifnir jealously guards.

|

| Siegfried |

|

| Fafnir guards the gold. Illustration by Arthur Reckham, 1911. |

· In the Christmas carol “Three Kings of Orient,” sung

by the three magi as they bring gifts to celebrate Christ’s birth in a manger,

the first king sings, “Born a king on Bethlehem plain, / Gold I bring to crown

him again.”

· During the Gold Rush of 1849 sailing vessels loaded

with would-be miners rushed to San Francisco, where whole crews deserted as well to

rush to the goldfields.

|

| A miners' ball in the goldfields. Alas, no women. |

· Bryan, the Great Commoner, was a champion of free

silver and a foe of gold and the Eastern bankers and railroad men who supported

it. In 1896 he won the Democratic

presidential nomination, though not the White House, with a fiery speech that ended, “You shall not crucify mankind upon a cross of gold!”

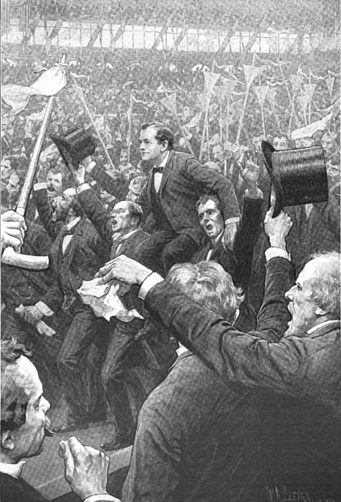

|

| Bryan's triumph, after the Cross of Gold speech. |

· Lincoln deplored the traders speculating feverishly in

gold on Wall Street during the Civil War.

· In Greek myth, King Midas of Phrygia got from the god

Dionysus the ability to turn anything he

touched to gold. In one version of the

story he embraces his daughter and she turns to gold. In another he starves to death, for the food

he tries to eat turns to gold.

|

| King Midas and his daughter. An illustration by Walter Crane, 1892. |

· The alchemists tried to turn base lead into gold.

|

| The Alchemist, engraving by Pieter Brueghel the Elder, 1558. |

· Fort Knox in Kentucky contains a fortified vault

holding a large portion of the nation’s gold reserves. It figures in popular culture, as in the 1959

James Bond film Goldfinger, when the

arch criminal Goldfinger hires Pussy Galore and her lesbian gang to drop

airborne poison to kill the garrison, so he can steal the gold.

|

| The gold vault, Fort Knox. |

All of which goes to show how gold fascinates, tempts,

deludes, and destroys man and womankind.

How come?

How indeed? The only

gold I’ve ever seen is in jewels and fillings, the jewels not mine, and the

fillings from my teeth – tiny bits and shavings – returned to me by a

scrupulous dentist who had replaced some fillings. Of course I’ve seen the gilt frames of

paintings in museums, so I suppose that counts, but the gilt didn’t belong to

me.

During and after the Civil War, men and sometimes women

gambled huge sums on the rise or fall in price of gold on Wall Street, their

eyes mesmerized by the fluctuating numbers displayed on a price indicator

posted outside the Gold Room on the street.

Yet few if any of them had ever seen real gold. All they were dealing with were certificates

and statements of account – paper, flimsy substitutes for gold. Yet the winners sported flashy rings, paraded

in fancy trotting wagons in Central Park, and invited friends to Delmonico’s to

dine on truffled veal. And the losers

ended up shuffling in seedy coats, boots unblackened, always asking prices,

lunching on bread and milk for a nickel.

What was real, what was fake?

Gold. The very word casts a spell, it excites,

it mesmerizes. Fisk and Gould tried to

corner it. Midas prized it above all

else, until he learned better. It was so

valued in Biblical times that legend has

the Magi bringing it to Bethlehem, along with frankincense and myrrh. In 1849 the

hope of finding it uprooted young men from the best New York families –

so-called Argonauts – and sent them by ship to Panama, to cross the rugged

spine of the continent by mule, and then sail from the Pacific side of the

isthmus to San Francisco, and from there on by land to the goldfields. Or they took a ship all the way around the

southern tip of South America and up to the same destination – a voyage that

took weeks -- in hopes of making a fortune in gold, though few did. The real fortunes were made by clever

merchants in San Francisco who sold mining and camping equipment to the miners,

and by moneyed opportunists who organized mining companies and hired the luckless

gold diggers to work in their mines, extracting gold from the depths of the

earth. Such extracting, in the minds of

the native peoples, was a violation of the Mother, a rape of the earth.

|

| A gold digger. An advertising card for Libby's Beef, ca. 1880. |

Gold digger – in twentieth-century parlance, a woman out to

snag a wealthy lover or husband. “I’m

not much of a gold digger,” I told the older gay male couple running the gay

rooming house I stayed at during my first and only visit to Provincetown, the

gay summer resort, in 1955. Not that I

hadn’t had my chance. I was 27, looked

24, and youth was esteemed, almost idolized, in gay Provincetown. After Labor Day the bus to the beach stopped

running, so I walked there and back; it was only a mile. Coming back one day with the beginning of a

tan, I was offered a ride into town by a man of about 40 in a Cadillac. Why not?

So I hopped in. He was well

dressed, well groomed, well bred, and well spoken; he and his Cadillac said money.

He asked what I did at night, where did I go? I was vague, then thanked him for the ride

and hopped out.

End of story? Not

quite. The following day I was walking

back again from the beach, when the same man in the same Cadillac offered me a

ride. Was he waiting for me, or for any

young kid coming back from the beach? I

didn’t know, but again I hopped in. Same

routine: courteously he asked about my plans for the evening, and everything whispered money. But I wasn’t comfortable in a Cadillac,

so I was vague again, thanked him, and got out.

Never saw him again. I hope he

found a kid in love with money and all that it can do. End of story?

No, a beginning. Soon afterward I

met a good-looking Canadian, age 30, with a Volkswagen. Thirty and 27: perfect. And a Volkswagen – just my cup of tea. And so …

But that’s another story. And my future partner Bob, at age 20, got an explicit offer from the first man he had sex with: "I can keep you good." But that too is another story; let's get back to gold.

|

| Gold Diggers of Broadway, a Broadway musical of 1929. |

So why all the fuss about it? It has always been valued the world over as a

kind of money. But it was more than

money. The ancients thought it was the

purest of metals, frozen God, a bridge to the spiritual, and used it in their

shrines and temples. Okay, valued since

antiquity, but why? Of all the many

elements, why was gold so valued?

Let’s have a look at those elements, many of which the

ancients didn’t even know. First of all,

you wouldn’t want to use a liquid or a gas as money, they might just evaporate

or flow away. And you wouldn’t want

anything radioactive like radium, or liable to rust like iron and copper and

lead, or apt to fizz and pop like sodium and potassium. Nor would you want anything that promptly decomposes like

uranium and plutonium, or anything that is hard to extract like aluminum. These conditions eliminate most of the solid

elements, leaving just two: silver and gold. But silver tarnishes, which is why we use

silver tea sets less today than in the old days, when there were servants to

polish it. So we end up with gold.

|

| Panning for gold in Queensland, Australia, 1900. |

Consider: gold is rare, but not impossibly rare. Chemically, it’s dullsville, not reacting

with anything, and therefore wonderfully inert.

It’s solid, portable, nontoxic, and it lasts. And alone of all metals, it’s golden, it’s

just plain beautiful to look at. Golden

objects found in ancient tombs – by excavators who don’t like the name of grave

robbers – still have their shape and shine.

But the real answer is that gold is valuable because we as a society

choose to value it. Like money, gold is

fiction. It lacks intrinsic value, but

takes on the value that we project onto it.

And a multitude of societies past and present – including most of those we know of

– have chosen to view it as valuable

In myth and legend, as in reality, gold is no. 1, silver is

no. 2. Gold is the sun, silver is the

moon. Gold is masculine, dominant. Silver is feminine, passive. See what you’re up against, feminists? But holy God, think of Medea, slaughtering

her unfaithful lover’s children, which are also her own. Or Clytemnestra, murdering her husband and his

trophy spoil from the ruins of Troy, the prophetess Cassandra, so she, Clytemnestra, can rule and hang out

with her fancy man, Aegisthus. – Some passive!

So gold is tops, the best, what we yearn for and want to

possess, which can be material or spiritual.

Like the legendary damsel in distress, it is the hero’s reward, won through acts

of courage. Wagner’s Siegfried wins both Brunnhilde and Fafnir's gold, thus achieving a rare double whammy. But gold is also the divine intelligence and supreme illumination, accessing which requires more than killing a mere dragon

or rescuing your future ladylove and wakening her to love. Maybe

gold is the dreamed-of unattainable, the buried treasure we search for all our

life but never quite discover. Maybe it is the light we go to after death. If so, we will all be rich in time, but not

with ingots of gold, much less clinking coins and greasy dollar bills.

|

| Gold bars. Stevebidmead |

Still, it’s hard not to think about real, material gold,

where it’s stored and who owns it. If

Fort Knox holds tons of it, New York does, too: the biggest stash of gold in

the world. In the underground vault of

the Federal Reserve Bank of New York at 33 Liberty Street are 497,000 bars of

gold, with a combined weight of 6,190 tons.

The vault can support this weight, because it rests on the bedrock of

Manhattan Island, 80 feet below street level and 50 feet below sea level. The value of it? Maybe $240 to $260 billion. And who does this treasure belong to? The government? Not at all.

It belongs to account holders who, to store it there, pay the government

a handling fee for every transaction.

The bars were once rectangular bricks, but since 1986 they have been

converted to the trapezoidal shape conforming to international standards. They are stored in padlocked compartments in

a depository safeguarded by a multilayered security system. The only entrance to the vault is protected

by a 90-ton steel cylinder set within a 140-ton steel-and-concrete frame that,

when closed, creates an airtight and watertight seal. And that’s only part of the security system

guarding the treasure. So, Goldfinger,

forget about it. Pussy Galore, you

haven’t got a chance.

But who requires such security? Who in this day and age wants to lock away

real gold bars in such a vault? Do they

fear a plunge in the value of the dollar, a financial convulsion making gold

look like a desirable refuge? One thinks

of the people who used to have secret bank accounts in Switzerland, before the

IRS and other nosy foreign entities came snooping around and pressured some of

those banks to reveal the names of depositors.

One imagines a Saudi prince, a Chinese plutocrat, a dictator fearing

overthrow, a moneyed U.S. divorcée still milking her ex for alimony. Maybe they too, when not buying a costly

pied-à-terre in a Manhattan high-rise, have gold bars stashed away in New

York’s underground Fort Knox. It must

give them a warm, yummy feeling of safety, of protection against the

fluctuations of markets, the whims and vicissitudes of time.

But no, it isn’t them at all. Most of the gold – 98% of it – belongs to the central banks of foreign nations, who consider the U.S. a safe place for gold because, even in the age of Trump, it is free from revolutions, civil wars, and other upheavals. Unless, of course, this is all fake news put out by the Fed itself, as various conspiracy theorists opine. After all, no one but select Fed employees are allowed to see the gold. So maybe it’s all a hoax. Maybe there is no such treasure at all deep in the guts of 33 Liberty Street. Something to think about, if you’re so inclined. But I’m not. For now, at least, I’ll take the Fed’s word for it, and wish those central banks well. So gold, whether mythical or real, still obsesses us, and probably always will. Poor silver, like Chicago, always no. 2. (Or 3, given the intrusion of that upstart, the City of the Angels.) So decree the markets, karma, and the gods of wealth. Or maybe just the dictates of the human mind, that quirky and capricious determinant. Maybe just us.

But no, it isn’t them at all. Most of the gold – 98% of it – belongs to the central banks of foreign nations, who consider the U.S. a safe place for gold because, even in the age of Trump, it is free from revolutions, civil wars, and other upheavals. Unless, of course, this is all fake news put out by the Fed itself, as various conspiracy theorists opine. After all, no one but select Fed employees are allowed to see the gold. So maybe it’s all a hoax. Maybe there is no such treasure at all deep in the guts of 33 Liberty Street. Something to think about, if you’re so inclined. But I’m not. For now, at least, I’ll take the Fed’s word for it, and wish those central banks well. So gold, whether mythical or real, still obsesses us, and probably always will. Poor silver, like Chicago, always no. 2. (Or 3, given the intrusion of that upstart, the City of the Angels.) So decree the markets, karma, and the gods of wealth. Or maybe just the dictates of the human mind, that quirky and capricious determinant. Maybe just us.

Coming soon: Fire. Or something else.

© 2019 Clifford Browder

No comments:

Post a Comment