For my fiction and nonfiction, scroll down past the post to BROWDERBOOKS.

A note on reviews:

A review of my novel Dark Knowledge has been included in the April 2018 issue of Reviewer's Bookwatch, the online book review magazine of Midwest Book Review. To see it, go here and scroll down.

If you read a book of mine or anyone's and enjoy it, tell your friends. Word-of-mouth is the best advertising there is.

And if you read a book of mine or anyone's, go the book's online page on Amazon or Barnes & Noble and do a customer's review. I have found it easier to get a book published than to get a review. (Yes, I'm serious.) A review doesn't have to be three paragraphs long; it can be three sentences or less. Anyone can do a review. And the review needn't be favorable, just honest. Better a bad review than no review at all.

SMALL TALK

What they said about New York:

"A hundred times I have thought New York a catastrophe, and fifty times: It is a beautiful catastrophe." Le Corbusier

"There is something in the New York air that makes sleep useless." Simone de Beauvoir

In an article in the New

York Times of March 29, 2018, producer and author Jacob Tobia protests the

preference in film and television for masculine gay male leads, as opposed to

feminine and gender-nonconforming gay men, who are only allowed to provide comic

relief. In so doing he tells how as an

undergraduate at Duke University he was outrageously and flamboyantly gay. He wore bright red lipstick and a full beard;

danced on a bar in a miniskirt, exposing his unshaven legs; and strutted

brazenly across cobblestones in four-inch heels. For half the gay men on campus he was an

inspiration and friend, and for the other half, an embarrassment. Those who were embarrassed wouldn’t speak to

him and even avoided eye contact, yet benefited from his presence, since his

being the campus freak let them get accepted as “normal” gay. The message for gay young people today, Tobia

insists, is that they must be the “right type of gay” – masculine, not

flamboyant femme – to be respected, accepted by their family, and desirable.

Tobia’s article underlines the divide in the gay community between

“normal” (i.e., masculine) gay and flamboyant femme gay that goes back as far

as I can remember. In my days as a

graduate student at Columbia University in the 1950s I can recall a gay Iranian

student complaining of “those characters who give homosexuality a bad name.” A very masculine gay man getting a master’s

degree in Library Science gave his friends glowing accounts of a gay bar in

Patterson, New Jersey, where “there isn’t a “broken wrist in sight,” that being

a stereotypical sign of femme gay. In

those less tolerant days, the majority of gay men distanced themselves from the

obviously gay, queenly types, even if sometimes, discreetly, they might

approach them for a romp in bed.

Memorable from my days at Columbia is a Puerto Rican kid

named Wally, not outrageously femme but a bit too exuberant to be straight, who

got a lot of attention and reveled in it.

“Cette folle” (“that madwoman”) a very masculine Haitian acquaintance of

mine labeled him and kept his distance, but a Jewish friend, a sophisticated

New Yorker, told me, when I described Wally to him, “I want to meet this

one.” Meet “this one” he did, not out of

sexual interest but curiosity, a curiosity that was satisfied with a single

encounter. Though I half kept my

distance, Wally confided in me how back in Puerto Rico his family had heard

strangers comment on his exuberant gayness.

The family solution was to have some cousins drop him off at a brothel

and wait till he reappeared, presumably no longer a virgin. Wally assured the cousins that all had gone

well, and so for the moment allayed the family’s suspicions. To pass the time in the brothel, he must have

entertained the girls with some of his stories, or maybe, like a friend of mine

once, joined them in a game of tiddlywinks.

When he got a chance to come to New York to study, Wally jumped at it

and left the family and its suspicions far behind in Puerto Rico. Wally was an entertainer, exuberant and

gregarious, but his entertaining ran big risks.

When he got a job teaching in a boys’ school, I predicted that he

wouldn’t last one term. Sure enough, the

kids caught on to him and he was summarily dismissed. What became of him after that I have no idea.

Another acquaintance from my first year at Columbia was

Jimmy, a rather sexy femme kid whose room was just across the hall from mine on

the fifteenth floor of John Jay Hall, where, quite by chance, two-thirds of the

guys were gay, but mostly “normal” gay.

A graduate student in English, Jimmy had a cute little black lover who

was often seen in the communal shower.

One morning, having just seen a very macho Marlon Brando in curly bangs

playing young Mark Antony in the film Julius

Caesar, Jimmy showed up in bangs.

|

| Jimmy's inspiration. |

But

if bangs enhanced the masculinity of a very quietly and confidently masculine

Brando, on Jimmy they came off as just plain weird. To my dismay, I found myself walking with

Jimmy to a 9:00 a.m. English class that we were both attending. Without being a close friend, I knew him too

well to avoid going with him, but feared the looks we would both soon get. Looks there were aplenty, but all at Jimmy; I

was scarcely noticed. Then, within a day

or two, the bangs were gone. His black

lover, he told me, had taken one look and announced, “You look like a Roman

whore.” That did it; the bangs

disappeared. At the end of the year

Jimmy announced that he had been drafted.

“Whatever my sergeant can do,” he told me, “I guess I can do, too.” What the consequences were for both Jimmy and

the Army I hesitate to say.

My memories stretch back as well to my undergraduate days at

Pomona College in Claremont, California.

There I honestly believed myself to be straight, but like many other

students, I was distantly tolerant of the “drama crowd” who starred repeatedly

in campus theater productions or otherwise helped make them happen. That crowd was presumably gay – the men, at

least – but they were tolerated as different, “artsy-fartsy,” marginal. One of them named Don – short, witty, cute --

seemed to revel in his “otherness” and reportedly proclaimed himself “as queer

as a two-dollar bill.” Far from clinging

to the shadows, Don often performed in the college productions, preferring

comic roles and doing a delicious Puck in Midsummer

Night’s Dream. Likable and harmless,

he was accepted as the campus queer. I

recall myself saying of him, “I don’t care what he is, as long as he leaves me

alone.” He achieved a new height of

notoriety when, with a perverse sense of humor, the Pomona coeds elected him the

King of Pomona, who then, in a gesture of friendship, was supposed to meet the

Queen of Occidental, our traditional rival in football. When they met, the poor girl from Occidental

stared, dumbfounded, as Don romped and reveled at the news of his election.

My memories go back even to my distant high school days in

the 1940s and a blond kid in my junior year journalism class named David. Back then being blond could automatically

make you suspect (mercifully, my blond hair had long since turned to brown),

and David, being very blond, reinforced the stereotype. In no way flamboyant, he was gently femme, a

likable guy who was simply, softly there.

And he could take a joke on himself.

When the class teacher read a bit of his writing that was much too rich,

too lush, inducing laughter in the class, David smiled sheepishly and said,

“I’m his straight man.” (“Straight man”

meaning the stone-faced partner in a comic team who acts as a foil to the

comic, delivering lines that let the comic respond and get the laughs.) The other kids liked David, an arch example

of the feminine boy who wished no harm to anyone and simply wanted to blend in. I have often wondered what became of him and

how he survived.

Another gay acquaintance from my graduate school years told

me how, when he outed himself to a straight friend, the friend replied, “Well,

you’re not obvious,” indicating that “normal” gay he could take. But when the time came for gay liberation, it

was the flamboyant drag queens who launched the Stonewall riots that got the

ball rolling. In the Gay Pride marches

that followed, everyone took part: the supermacho leather crowd, the drag

queens, and the legions of gay guys whom most people wouldn’t take for

gay. When I marched with the Whole Foods

Project in June 1994, just a month after surgery for cancer, behind our

contingent in the parade was a delegation from San Francisco. Most of them were in T-shirts and shorts like

the other marchers, but the front row and the leader took drag to a new

level. Instead of presenting themselves

as women, or caricatures of women, their outlandish costumes made them come off

as creatures from another universe: drag transformed into sci-fi.

|

| London Pride, 2017. Fae |

Of course there were gay detractors who denounced the

parades as giving ammunition to homophobes, who could then show photos of

militant drag queens and ask, “Do you want your children to be taught in the

schools by these people?” I saw many of

the parades over time but never felt that they were a mistake, no matter how

wild a few of the participants might be.

The parade was – and is -- the gay Mardi Gras, that once-a-year event

where anything goes.

A femme gay whose name became a household word was Andy

Warhol, the Prince of Pop, whose art was in his own time controversial, but

sells today for phenomenal prices. My

friend John, who knew him early in his career in the 1950s, described him as

friendly, accessible, and “featherly,” a gentle, soft-voiced soul. Photos from that period show a delicately featured

young man with long blond hair and glasses, femme in the extreme. But “femme” needn’t mean passive and

mild. By the 1960s his studio on East 47th

Street, dubbed the Factory, was a magnet for avant-garde artists, writers,

musicians, celebrities, drug addicts, and assorted weirdos, over whom he ruled

tyrannically. Only a near-fatal bullet

wound from the radical feminist Valerie Solanas in 1968 ended that phase of his

career. He lived another nineteen years,

but time was not kind to him; later photos show a gaunt face framed by long

graying hair that often looked like a fright wig.

|

| Andy Warhol, 1977. |

A rare example of quietly assertive femme gay was Quentin

Crisp, the self-styled “Stately Homo of England,” who at age 70, already a

celebrity by virtue of his memoir, The

Naked Civil Servant, came to these shores in 1978 to do his one-man show

and, falling in love with New York, returned to stay. He was persistently and unashamedly femme,

and in getting himself accepted and even acclaimed as such, worked a minor

revolution. Perennially onstage and

easily recognized by his painted face and black, wide-brimmed hat tilted

rakishly, he coasted on his wit. A

gregarious loner, he distanced himself from the gay lib movement that had got

its start right here in New York, yet benefited from the tolerance that

movement generated. In spite of himself,

he was a part of it.

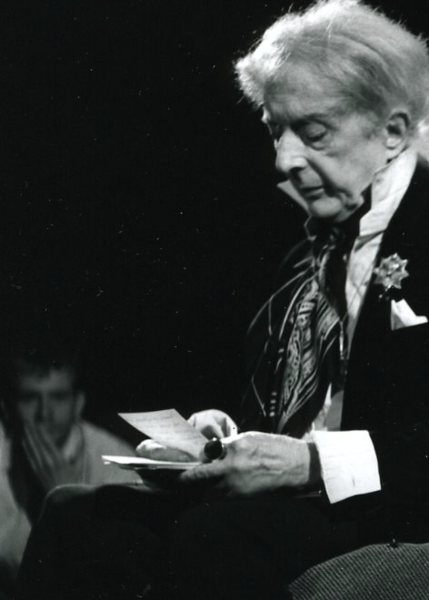

|

| Quentin Crisp, 1996. Ross B. Lewis |

The success of Andy Warhol and Quentin Crisp shows that

feminine gays could achieve a welcome notoriety and a degree of acceptance in

New York that would have been inconceivable some years earlier. When Mart Crowley’s play The Boys in the Band was produced Off Broadway in 1968, it was the

one of the first plays with gay men in the leads. Especially memorable was Emory, a flamboyant

interior decorator who made the rest of the cast look “normal.” Some of my gay friends took exception to

Crowley’s portrayal of the gay world, but the reviews were generally favorable,

and a film followed in 1970.

Acceptance, yes, but not without risks. I recall a directors class at the Actors

Studio in the 1960s where a gay actor presented a shapeless happening with

himself, a younger gay actor, and a young women performing. It wasn’t a play and was criticized as such. At one point the younger actor did a monolog

that began with his announcing, “I feel so oral.” In what followed he came off as decidedly

gay, with discreet suggestions of oral sex.

An actor in the class told of seeing the non-play performed for the

public, and of observing a straight guy in the audience, attending in the

company of his girl, seething with barely suppressed rage. He felt threatened in his manhood by the

monolog, and the result might well have been violent. And this in easygoing, tolerant New York.

How it was in the rest of the country became apparent with

an incident in Bangor, Maine, in 1984.

Charlie Howard was a flamboyantly gay 23-year-old, blond and slight of

build, who if he felt like “sissying up” -- wearing makeup and jewelry and

coming off as flagrantly femme -- did so.

Bullied in high school in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, he didn’t attend

graduation so his parents wouldn’t hear the taunts he was sure to receive. Coming to Bangor, Maine, Charlie made new

friends, joined a gay-friendly Unitarian church, got an apartment, and adopted

a kitten. When a woman in a local market

shouted at him, “You pervert! You

queer!” he got frightened and left, but as he did so, he blew her a

kiss. Then, leaving his apartment one

day, he found his kitten on the doorstep, strangled.

Matters came to a head on the evening of July 7, 1984. As Charlie and a friend were walking across a

bridge over the Kenduskeag River, a car with five high school kids -- three boys and two girls who had been drinking -- stopped. Leaving the two girls in the car, the three boys got out and attacked Charlie.

Charlie’s friend escaped, but the boys caught Charlie, beat him, and

started lifting him over the bridge’s railing.

“Don’t,” pleaded Charlie, “I can’t swim!” Ignoring his pleas, they pried his hand loose

from the railing and pushed him over, then returned to the car and left. Unaware of Charlie’s fate, they went to a

party and boasted of what they had done. But Charlie had drowned; his body was recovered the next day. When they learned of his death, the two girls went to the police and told what they had witnessed. Arrested,

the boys were arraigned in court. A

photo of them in police custody and handcuffed, ages 15, 16, and 17, shows

vividly just how young they were. The

judge had to decide whether they should be tried for murder as adults, or for

manslaughter as juveniles. Public

opinion was sharply divided. Some argued

the three were just “boys being boys,” and insisted that Charlie’s outlandish

behavior had provoked the attack. His

defenders staged a demonstration and labeled his death a hate crime deserving

the most severe penalty. The judge

acknowledged the seriousness of the offense, but cited the boys’ lack of any

criminal record and therefore charged them as juveniles with manslaughter. They pleaded guilty, served up to two years

in a juvenile detention center and, as required by state law, were all out by age 21.

Twenty-five years later one of the boys, now a middle-aged

man living in Bangor, said in an interview that he spoke regularly advocating

tolerance of sexual deviation and thought of Charlie every day of his life. A memorial to Charlie was installed on the

site of his death, but in 2011 it was vandalized with spray-painted graffiti. July 7, the date of Charlie’s death, is now

celebrated as Diversity Day in Bangor.

Every year on that date people drop flowers into the Kenduskeag River,

saying, “Charlie, this is for you.”

I find Charlie Howard’s story heartbreaking in the

extreme. But beyond that, what do I

conclude? Some gay men are driven by a

deep-seated urge to be flamboyant, to throw their gayness in the face of

society, to be perennially and conspicuously onstage. Maybe it’s their revenge for being gay, or a

need for attention at whatever cost, or even a kind of death wish. Certainly, like Charlie, they refuse to not

be who they are. But while “normal” gay

men manage today to live quietly without too much to-do, their flamboyant

brothers still court danger and sometimes even death.

Coming soon: The 9/11 Museum: My Descent into the Land of the Dead

Coming soon: The 9/11 Museum: My Descent into the Land of the Dead

BROWDERBOOKS

All books are available online as indicated, or from the author.

1. No Place for Normal: New York / Stories from the Most Exciting City in the World (Mill City Press, 2015). Winner of the Tenth Annual National Indie Excellence Award for Regional Non-Fiction; first place in the Travel category of the 2015-2016 Reader Views Literary Awards; and Honorable Mention in the Culture category of the Eric Hoffer Book Awards for 2016. All about anything and everything New York: alcoholics, abortionists, greenmarkets, Occupy Wall Street, the Gay Pride Parade, my mugging in Central Park, peyote visions, and an artist who made art of a blackened human toe. In her Reader Views review, Sheri Hoyte called it "a delightful treasure chest full of short stories about New York City."

If you love the city (or hate it), this may be the book for you. An award winner, it sold well at BookCon 2017.

"If you want wonderful inside tales about New York, this is the book for you. Cliff Browder has a way with his writing that makes the city I lived in for 40 plus years come alive in a new and delightful way. A refreshing view on NYC that will not disappoint." Five-star Amazon customer review by Bill L.

Available from Amazon and Barnes & Noble.

|

2. Bill Hope: His Story (Anaphora Literary Press, 2017), the second novel in the Metropolis series. New York City, 1870s: From his cell in the gloomy prison known as the Tombs, young Bill Hope spills out in a torrent of words the story of his career as a pickpocket and shoplifter; his brutal treatment at Sing Sing and escape from another prison in a coffin; his forays into brownstones and polite society; and his sojourn among the “loonies” in a madhouse, from which he emerges to face betrayal and death threats, and possible involvement in a murder. Driving him throughout is a fierce desire for better, a persistent and undying hope.

For readers who like historical fiction and a fast-moving story.

Reviews

"A real yarn of a story about a lovable pickpocket who gets into trouble and has a great adventure. A must read." Five-star Amazon customer review by nicole w brown.

"This was a fun book. The main character seemed like a cross between Huck Finn and a Charles Dickens character. I would recommend this." Four-star LibraryThing review by stephvin.

Available from Amazon and Barnes & Noble.

3. Dark Knowledge (Anaphora Literary Press, 2018), the third novel in the Metropolis series. Adult and young adult. A fast-moving historical novel about New York City and the slave trade, with the sights and sounds and smells of the waterfront.

The back cover summary:

New York City, late 1860s. When young Chris Harmony learns that members of his family may have been involved in the illegal pre-Civil War slave trade, taking slaves from Africa to Cuba, he is appalled. Determined to learn the truth, he begins an investigation that takes him into a dingy waterfront saloon, musty old maritime records that yield startling secrets, and elegant brownstone parlors that may have been furnished by the trade. Since those once involved dread exposure, he meets denials and evasions, then threats, and a key witness is murdered. Chris has vivid fantasies of the suffering slaves on the ships and their savage revolts. How could seemingly respectable people be involved in so abhorrent a trade, and how did they avoid exposure? And what price must Chris pay to learn the painful truth and proclaim it?

Early reviews

"A lively and entertaining tale. The writing styles, plot, pace and character development were excellent." Four-star LibraryThing early review by BridgitDavis.

"A lively and entertaining tale. The writing styles, plot, pace and character development were excellent." Four-star LibraryThing early review by BridgitDavis.

"At first the plot ... seemed a bit contrived, but I was soon swept up in the tale." Four-star LibraryThing early review by snash.

"I am glad that I have read this book as it goes into great detail and the presentation is amazing. The Author obviously knows his stuff." Four-star LibraryThing early review by Moiser20.

4. The Pleasuring of Men (Gival Press, 2011), the first novel in the Metropolis series, tells the story of a respectably raised young man who chooses to become a male prostitute in late 1860s New York and falls in love with his most difficult client.

What was the gay scene like in nineteenth-century New York? Gay romance, if you like, but no porn (I don't do porn). Women have read it and reviewed it. (The cover illustration doesn't hurt.)

What was the gay scene like in nineteenth-century New York? Gay romance, if you like, but no porn (I don't do porn). Women have read it and reviewed it. (The cover illustration doesn't hurt.)

Reviews

"At times amusing, gritty, heartfelt and a little sexy -- this would make a great summer read." Four-star Amazon customer review by BobW.

"Really more of a fantasy of a 19th century gay life than any kind of historical representation of the same." Three-star Goodreads review by Rachel.

"The detail Browder brings to this glimpse into history is only equaled by his writing of credible and interesting characters. Highly recommended." Five-star Goodreads review by Nan Hawthorne.

Available from Amazon and Barnes & Noble.

© 2018 Clifford Browder

> For half the gay men on campus he was an inspiration and friend, and for the other half, an embarrassment. Those who were embarrassed wouldn’t speak to him and even avoided eye contact, yet benefited from his presence, since his being the campus freak let them get accepted as “normal” gay.

ReplyDeleteExcuse me?! How utterly laughable to think that playing the caricature of class clown, deliberately going against the social grain, is endearing to anyone, particularly when done to a camp-tier level of performativity and with such a tacky and obvious thirst for attention.

I, and the other "masc", "normal" gays never needed Tobia's Walmart brand of gay evangelism to find our niches in social circles to preach by quiet, humble example.

It's on you if you CHOOSE to be the fem, flambouyant, garish fuckup comic relief in whatever you consider your ensemble cast. You're 100% free to cast yourself as that.

But please don't pretend that you're doing anyone but yourself a favor. I've had sloppy, drunk blowjobs that were more "helpful" than having a constant clown co-branding himself with me, who hogs the spotlight, who think he's "doing the work", that he's a "leader" and "driving progress" - you people really cannot read a room.