No Place for Normal: New York / Stories from the Most Exciting City in the World. A selection of posts from this blog.

Historical fiction set in nineteenth-century New York:

1. The Pleasuring of Men. A young man becomes a male prostitute in the hidden gay world of that time.

2. Bill Hope: His Story. A street kid turned pickpocket pours out his story in a torrent of words.

3. Dark Knowledge. A young man fights to discover the truth about his family's involvement in the slave trade.

For details, see below.

Instruments of Death

While doing the recent post on famous last words and gestures, I was drawn inevitably to the related topic of how we humans put our outcasts and offenders to death -- a grisly subject, irresistible. One thinks at once of Socrates, convicted in ancient Athens of impiety and corrupting the youth with his endless barrage of questions about our values and how we should live – questions that had indeed brought the youth of Athens flocking to him, as he wandered the streets and questioned the good citizens whom he encountered. As his disciple Plato, who knew eyewitnesses, tells it, Socrates was given a cup of poison hemlock to drink and then, having cheerfully drunk it, felt a numbness rising through his legs; when the numbness reached his heart, he died. All this occurred quite peacefully and painlessly, while his disciples wept.

According to Plato’s dialogue Phaedo, this was a merciful way of disposing of a troublemaker; no blood was shed, and the condemned became his own executioner. The agent of death, poison hemlock (Conium maculatum), is a plant that I know well, having seen it growing about three feet high in a shady spot – I won’t say exactly where – in Van Cortland Park. It is a common plant of the parsley family, the Umbelliferae, that prefers waste ground; its grooved stem has purple spots, its leaves are fernlike, and its tiny white flowers top the stem in umbrella-shaped clusters. Not a plant flaunting gaudy flowers or begging for attention; most people, if they notice it at all, would dismiss it as a weed. But yes, its juices are very poisonous.

|

| The plant that did in Socrates. Lacelike, but lethal. vastateparkstaff |

If anyone, envying Socrates’ dignified passing, is tempted to follow his example by drinking hemlock juice, be advised: the symptom of hemlock poisoning is indeed a mounting paralysis, but there can also be vomiting, trembling, urination, nausea, and convulsions, all of which make the whole business sound rather messy. If one must do away with oneself, why not a simple bullet to the brain? More efficient, provided a gun is handy and one’s aim is good.

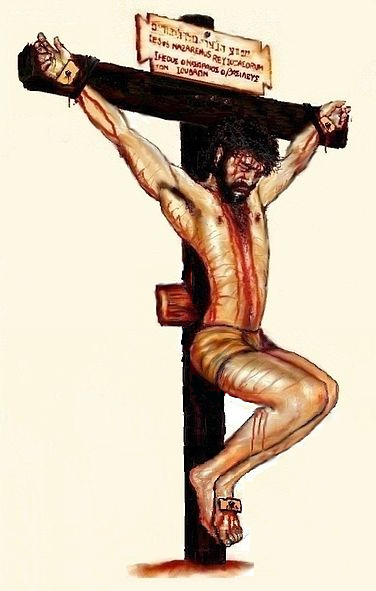

The other famous execution in the history of the West was, of course, the crucifixion of Jesus. Though Jesus was convicted by the Jews, it was the Romans who put him to death, and for them crucifixion was the most dishonorable death imaginable, appropriate for slaves and foreigners, including, in time, Christians, but only rarely Roman citizens of the lower classes; Constantine the Great, the first Christian emperor, abolished it in the fourth century CE. Unknown in pre-Hellenic Greece, crucifixion had originated in Persia and then been perfected – if such a word is appropriate – by the Romans. It was indeed a horrible death, for the weight of the body tugging down on the arms made breathing difficult, leading to suffocation. Also, as blood drained from the wounds, the heart and lungs stopped functioning, and the seven-inch nails driven through the hands caused intense pain. It was a very public and painful way of dying; few victims lasted more than twenty-four hours, often less.

|

| A modern representation, showing the effect of the body's weight, and the bleeding. Ruben Betanzo S. |

So how did the Romans execute Roman citizens guilty of murder? If you killed a Roman citizen of equal rank, you weren’t executed at all; you simply paid a fine or suffered what was considered a truly harsh fate: exile. If a citizen was put to death, which was rare, it was by beheading, which was considered a more honorable death. And if a citizen killed a slave or someone of lesser status, there was no punishment at all. As for slaves and prisoners of war, they could be tossed to wild bears, lions, or bulls, which made for a fine show at the Colosseum. Such was the fate of the early Christians, unless they could claim Roman citizenship. But for an even better spectacle, the offenders could be tied to the tails of stampeding horses and dragged to their death.

The Jews had several ways of executing. Stoning was used for certain offenses, but complicating the matter was the belief that the body should not be mutilated. When the scribes and pharisees confronted Jesus with a woman taken in adultery and asked if, in accordance with Mosaic law, she should be stoned to death, Jesus replied that he who had never sinned should throw the first stone and then dismissed her, telling her to go and sin no more (John 7:53-8:11). Burning was also used by the Jews, as well as decapitation by the sword and strangulation, this last being thought more humane and the least mutilating.

In ancient Britain the Celts executed by throwing the victim into a quagmire. In medieval Britain the barons had a gallows for hanging, and a drowning pit as well. The upper classes were merely beheaded, but women of the lower classes were burned for treason, and men were hanged, drawn, and quartered. Those who wouldn’t confess their crimes were subjected to pressing: the executioner placed heavy weights on the victim’s chest until he either confessed or died. And the offenses meriting the death penalty included theft, cutting down a tree, counterfeiting, and marrying a Jew. Then in 1531, as the Renaissance brought enlightenment, boiling was approved, and some victims boiled for up to two hours before dying.

|

| The execution of Sir Walter Raleigh. His rank gave him the privilege of a beheading. |

Britain of course exported its modes of execution to the thirteen American colonies, though each colony went its own merry way. Hanging was the commonest means of execution, and many were the crimes that merited it. In 1612 Virginia’s governor decreed the death penalty even for stealing grapes, killing chickens without permission, or trading with Indians, but seven years later these laws were softened, because the government in its belated wisdom realized that otherwise no one would want to settle there. In the 1630s Massachusetts imposed the death penalty for murder, sodomy, witchcraft, adultery, idolatry, blasphemy, assault, rape, statutory rape, manstealing, perjury, rebellion, manslaughter, poisoning, and bestiality. The victims of the infamous Salem witch trials of 1692, mostly women, were hanged, though one man who refused to confess was pressed to death.

|

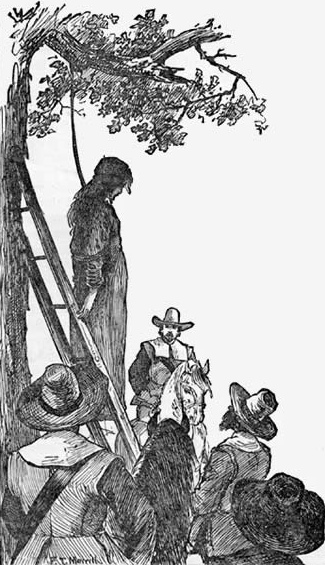

| Execution of Ann Hibbins for witchcraft on Boston Common in 1656, years before the witch hunt in Salem. |

The American colonies would in time revolt against the rule of George III, but in Europe monarchy had long prevailed, and the crime of regicide was viewed with horror and punished accordingly. François Ravaillac, the Catholic zealot who stabbed Henry IV of France to death in 1610, was condemned to death and taken to the Place de Grève, where he was scalded with burning sulfur and molten lead, following which his flesh was torn with pincers and he was drawn and quartered. This last involved tying the victim’s limbs to four horses that were then sent galloping in four directions, tearing the victim apart.

|

| The execution of Ravaillac. An engraving of 1610. |

This same fate, following hanging, was announced for Guy Fawkes, the Catholic conspirator who tried to blow up the Houses of Parliament in England in 1606. While climbing up to the scaffold, however, he jumped from the ladder, broke his neck, and died instantly, thus depriving those present of a memorable spectacle.

For public spectacle, nothing outdid the auto-da-fé (“act of faith” in Portuguese) of the Spanish Inquisition, an elaborate ceremony prepared a month in advance, when the local authorities believed they had enough prisoners to justify the event. Suspects were subjected to secret examinations by inquisitors that involved torture to encourage confessions. Then, following an all-night vigil with prayers by the populace, and a Mass at daybreak with breakfast for those attending, the accused were brought out and the procession began. Wearing pointed caps and symbols identifying the offenses they were accused of, the prisoners, still unidentified and unaware of their fate, were paraded through the streets to the quemadero (“burning place”) outside the city, where the sentences were read. Those acquitted fell on their knees in thanksgiving; those convicted of heresy or other crimes were then “relaxed” to the secular authorities to be whipped, tortured, and burned at the stake. This “relaxation” occurred because the Church professed to abhor blood and therefore let the secular authorities do the dirty work. Among the victims were Jews, Moors, Protestants, and crypto-Muslims, as well as those guilty of lesser offenses like bigamy. Auto-da-fés were also held in Portugal, Brazil, and Mexico; thousands died. The last one in Spain occurred in 1826.

|

| An auto-da-fe of 1716. Judgment of the accused, a lesson for the populace, and a time for penitence. The whole town is involved. |

|

| Heretics burned at the stake in the marketplace. |

Inevitably, such practices came under scrutiny in modern times. Enlightenment thinkers and Quaker reformers urged revision of laws to limit or eliminate the death penalty. Especially influential was the Italian jurist Cesare Beccaria’s work On Crimes and Punishment, first published in English in 1767, which argued for the death penalty’s abolition.

In America various states passed laws against public hangings, which had become the scenes of rowdiness and drunken brawls, and in 1846 Michigan became the first state to abolish the death penalty, except for treason against the state. But opposition to reform was vehement, and the issue became controversial and remains so to this day. If hanging became a part of the tradition of the Old West where, for want of a gallows, a sturdy tree outside town with an appropriate horizontal branch was christened “the hanging tree,” the more progressive states of the East, viewing hanging as barbaric, looked for alternatives. Always in the forefront of progress, New York State in 1888 dismantled its gallows and built the nation’s first electric chair, which went into action – clumsily, it might be noted – in 1890.

|

| The famous electric chair of Sing Sing prison, New York. |

Even the West came to embrace change: in 1924 the state of Nevada performed the first execution by cyanide gas in a hastily constructed gas chamber. When Arizona first executed a woman in 1930, the hangman misjudged the drop and the victim’s head was ripped from her body, a contretemps that encouraged other states to switch to the electric chair or the gas chamber. And in 1977 the state of Oklahoma officially adopted lethal injection for executions, and in 1981 Texas became the first state to actually use it. In killing its condemned, America was doing its best to be civilized. And far from making the death throes a spectacle, we have made executions private, with only a few witnesses allowed to watch.

|

| The gas chamber of New Mexico Penitentiary, Santa Fe, in 2008. Shelka04 at en.wikipedia |

Meanwhile the French, so often in the vanguard of progress, had solved the problem of quick, painless, scientific killing in their own distinctive way. On October 10, 1789, the States General, summoned to consider needed reforms, was addressed by one of its members, Dr. Joseph-Ignace Guillotin, who in a debate on capital punishment proposed that criminals be beheaded painlessly by means of a simple mechanism that would be far more efficient than beheading by ax or sword, the punishment reserved for the nobility, or hanging, the punishment meted out to commoners. He was in fact opposed to the death penalty, and hoped that his “simple machine,” decapitating nobility and commoners alike, would be more democratic, and serve as a first step toward abolishing capital punishment. In a follow-up speech on December 1, 1789, he said, “Now, with my machine, I cut off your head in the twinkling of an eye (“clin d’oeil”), and you never feel it!” His statement immediately became a popular joke, and a comic song soon circulated, linking his name to the machine, which – to his keen regret – became known as the “guillotine.”

|

| The execution of Marie Antoinette, 1794. A contemporary engraving. Note the wicker basket in place to receive the head. |

In 1791 the National Assembly, which had evolved from the States General, made decapitation the only form of capital punishment in France. The head executioner, Charles-Henri Sanson, then pointed out that beheading by sword required dozens of executioners and scores of swords, and explained that swords broke easily, and that he had only two. As a result the Assembly in the spirit of progress embraced Dr. Guillotin’s invention, the guillotine. Sanson tested it first on animals, then on corpses of women and children obtained from a hospital; when male corpses proved a bit more resistant, the machine was redesigned to sever all heads efficiently, and was soon beheading nobles and commoners alike, and even the former king and queen, and finally and climactically, that evil genius of the Reign of Terror, Maximilien Robespierre himself. Not only was the guillotine embraced with enthusiasm, but it even inspired a children’s toy with a movable blade, and the kids were soon decapitating dolls and rodents. Marvelously effective, Guillotin’s invention was used for executions in France until capital punishment was abolished in 1981. Detrimental to its reputation, no doubt, was its use by Nazi Germany to execute some 16,500 people between 1933 and 1945.

|

| The lethal injection room at San Quentin State Prison in California, 2010. About as neat as they come. |

So why was the guillotine never adopted in the U.S.A.? It might seem to be the logical solution for a country that came to view hanging as barbaric, especially when the victim was seen twitching and choking in midair, or even defecating. But first, the various states tried a high-tech solution, either the electric chair, the gas chamber, or lethal injection, none of which proved effective, swift, and humane. Those electrocuted sometimes survived the first jolt of electricity, and sparks, smoke, and flames were emitted amid the odor of burnt flesh. Those executed in the gas chamber were seen to be choking and suffering; their eyes popped and they drooled. Lethal injection often took up to an hour because the victim was a drug addict and had few veins that could be injected; meanwhile the victim might be moaning, and in one case the syringe fell out of the vein and almost sprayed the witnesses with lethal chemicals. In desperation, some Western states turned to the firing squad. In 2016 Utah allowed condemned inmates to choose the firing squad as an alternative to lethal injection, and Oklahoma made it the official plan B, should lethal injection ever be ruled illegal. But firing squads shed blood, and our modern sensitivity finds that just as objectionable as gasping, twitching bodies, drooling or defecation, and the odor of burnt flesh.

|

| A firing squad in Mexico im 1913. |

So why not the guillotine? Because it involves a severed head and blood. Because we remember the French Revolution, with the executioner exhibiting the severed head to the mob, while Madame Defarge and her cohorts supposedly knitted. We want our executions to be clean and bloodless, and the corpse to remain intact. The guillotine is swift and painless, but it still offends us and leaves us looking for an alternative that probably does not exist. Killing is by nature messy and violent; it cannot be neat and hygienic. So as long as it is legal, as it still is in thirty-one states, the dilemma persists. But at least we have made it private.

BROWDERBOOKS

If you love the city (or hate it), this may be the book for you. An award winner, it sold well at BookCon 2017.

Review

"If you want wonderful inside tales about New York, this is the book for you. Cliff Browder has a way with his writing that makes the city I lived in for 40 plus years come alive in a new and delightful way. A refreshing view on NYC that will not disappoint." Five-star Amazon customer review by Bill L.

Available from Amazon and Barnes & Noble.

For readers who like historical fiction and a fast-moving story.

"A real yarn of a story about a lovable pickpocket who gets into trouble and has a great adventure. A must read." Five-star Amazon customer review by nicole w brown.

"This was a fun book. The main character seemed like a cross between Huck Finn and a Charles Dickens character. I would recommend this." Four-star LibraryThing review by stephvin.

"This is an easy read about a hard life. Interesting characters, a bustling city, poverty, privilege, crime, injustice combine to create a captivating tale." Five-star Goodreads review by John Wheeler.

3. Dark Knowledge (Anaphora Literary Press, 2018), the third novel in the Metropolis series. Release date January 5, 2018, but copies now available from the author. Adult and young adult. A fast-moving historical novel about New York City and the slave trade, with the sights and sounds and smells of the waterfront. More excerpts to come.

BROWDERBOOKS

All books are available online as indicated, or from the author.

1. No Place for Normal: New York / Stories from the Most Exciting City in the World (Mill City Press, 2015). Winner of the Tenth Annual National Indie Excellence Award for Regional Non-Fiction; first place in the Travel category of the 2015-2016 Reader Views Literary Awards; and Honorable Mention in the Culture category of the Eric Hoffer Book Awards for 2016. All about anything and everything New York: alcoholics, abortionists, greenmarkets, Occupy Wall Street, the Gay Pride Parade, my mugging in Central Park, peyote visions, and an artist who made art of a blackened human toe. In her Reader Views review, Sheri Hoyte called it "a delightful treasure chest full of short stories about New York City."

If you love the city (or hate it), this may be the book for you. An award winner, it sold well at BookCon 2017.

Review

"If you want wonderful inside tales about New York, this is the book for you. Cliff Browder has a way with his writing that makes the city I lived in for 40 plus years come alive in a new and delightful way. A refreshing view on NYC that will not disappoint." Five-star Amazon customer review by Bill L.

Available from Amazon and Barnes & Noble.

|

2. Bill Hope: His Story (Anaphora Literary Press, 2017), the second novel in the Metropolis series. New York City, 1870s: From his cell in the gloomy prison known as the Tombs, young Bill Hope spills out in a torrent of words the story of his career as a pickpocket and shoplifter; his brutal treatment at Sing Sing and escape from another prison in a coffin; his forays into brownstones and polite society; and his sojourn among the “loonies” in a madhouse, from which he emerges to face betrayal and death threats, and possible involvement in a murder. Driving him throughout is a fierce desire for better, a persistent and undying hope.

For readers who like historical fiction and a fast-moving story.

Reviews

"A real yarn of a story about a lovable pickpocket who gets into trouble and has a great adventure. A must read." Five-star Amazon customer review by nicole w brown.

"This was a fun book. The main character seemed like a cross between Huck Finn and a Charles Dickens character. I would recommend this." Four-star LibraryThing review by stephvin.

Available from Amazon.

3. Dark Knowledge (Anaphora Literary Press, 2018), the third novel in the Metropolis series. Release date January 5, 2018, but copies now available from the author. Adult and young adult. A fast-moving historical novel about New York City and the slave trade, with the sights and sounds and smells of the waterfront. More excerpts to come.

The back cover summary:

New York City, late 1860s. When young Chris Harmony learns that members of his family may have been involved in the illegal pre-Civil War slave trade, taking slaves from Africa to Cuba, he is appalled. Determined to learn the truth, he begins an investigation that takes him into a dingy waterfront saloon, musty old maritime records that yield startling secrets, and elegant brownstone parlors that may have been furnished by the trade. Since those once involved dread exposure, he meets denials and evasions, then threats, and a key witness is murdered. Chris has vivid fantasies of the suffering slaves on the ships and their savage revolts. How could seemingly respectable people be involved in so abhorrent a trade, and how did they avoid exposure? And what price must Chris pay to learn the painful truth and proclaim it?

Early reviews

"A lively and entertaining tale. The writing styles, plot, pace and character development were excellent." Four-star LibraryThing early review by BridgitDavis.

"A lively and entertaining tale. The writing styles, plot, pace and character development were excellent." Four-star LibraryThing early review by BridgitDavis.

"At first the plot ... seemed a bit contrived, but I was soon swept up in the tale." Four-star LibraryThing early review by snash.

"I am glad that I have read this book as it goes into great detail and the presentation is amazing. The Author obviously knows his stuff." Four-star LibraryThing early review by Moiser20.

"I am glad that I have read this book as it goes into great detail and the presentation is amazing. The Author obviously knows his stuff." Four-star LibraryThing early review by Moiser20.

4. The Pleasuring of Men (Gival Press, 2011), the first novel in the Metropolis series, tells the story of a respectably raised young man who chooses to become a male prostitute in late 1860s New York and falls in love with his most difficult client.

What was the gay scene like in nineteenth-century New York? Gay romance, if you like, but no porn (I don't do porn). Women have read it and reviewed it. (The cover illustration doesn't hurt.)

Reviews

"At times amusing, gritty, heartfelt and a little sexy -- this would make a great summer read." Four-star Amazon customer review by BobW.

"Really more of a fantasy of a 19th century gay life than any kind of historical representation of the same." Three-star Goodreads review by Rachel.

"The detail Browder brings to this glimpse into history is only equaled by his writing of credible and interesting characters. Highly recommended. Five-star Goodreads review by Nan Hawthorne.

Available from Amazon and Barnes and Noble.

What was the gay scene like in nineteenth-century New York? Gay romance, if you like, but no porn (I don't do porn). Women have read it and reviewed it. (The cover illustration doesn't hurt.)

Reviews

"At times amusing, gritty, heartfelt and a little sexy -- this would make a great summer read." Four-star Amazon customer review by BobW.

"Really more of a fantasy of a 19th century gay life than any kind of historical representation of the same." Three-star Goodreads review by Rachel.

"The detail Browder brings to this glimpse into history is only equaled by his writing of credible and interesting characters. Highly recommended. Five-star Goodreads review by Nan Hawthorne.

Available from Amazon and Barnes and Noble.

Coming soon: Authors Are Whores.

© 2017 Clifford Browder

This comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

ReplyDelete