The release date for Bill Hope: His Story was May 17, so those who have already ordered it from Amazon should be receiving it shortly, and anyone who wishes to order it can do so and have it promptly shipped.

For six LibraryThing prepublication reviews of Bill Hope:

His Story by viennamax, stephvin, Cricket2014, Shoosty, terry19802, and graham072442, go here and scroll down.

______________________________________________________________________

This post continues my chronicle of weird, unusual, and

unique professions in the city of New York.

Pornographer. Unusual?

Hardly; they’re found in every city, town, and village in the

country. But not everyone has been

hailed as the Sultan of Smut, least of all the last such operator in Times

Square. So meet Richard Basciano, a

Baltimore-born former bricklayer and boxer who began selling sex magazines and

buying real estate in New York in the early 1960s. I remember those racy, turbulent days, when

revolution and sexual freedom seemed to run rampant, and a street-corner newsie

would ask his customers, “Do you want a Screw?”

and whisk out from underneath the New

York Times a copy of Screw

magazine rife with porn. In such an

atmosphere Mr. Basciano, who considered pornography not harmful to the

community and even a deterrent to rape, was destined to prosper, and prosper he

did.

|

| 42nd Street in 1985. Ah, those were the days...! |

This was a time when 42nd Street between Seventh

and Eighth Avenues, close to that mecca for tourists, Times Square, had become

a lively and very conspicuous site for porn, and Mr. Basciano’s seedy

storefronts, offering peep shows and more for a quarter, in time would net him

millions. I remember that block, for

whenever I found myself in the neighborhood, I would walk the downtown side of

the street in the early evening to drink in the seedy atmosphere: old

movie-house marquees proclaiming

ADULT

MOVIES

HOTTEST

LIVE ACTS IN US

GIRLS

GIRLS GIRLS

and the sidewalk seasoned

with porn-hungry tourists, Puerto Rican hustlers, and flamboyant young drag

queens keeping an eye out for the “bulls,” their term for the police. I’m sure that, without realizing it, I was

walking by Mr. Basciano’s properties, too.

In 1977 his Show World Center theater opened at the corner

of West 42nd Street and Eighth Avenue, a flashy 22,000-square-foot

supermarket of porn occupying four floors of a twelve-story building, and topped

by a three-floor penthouse where Mr. Basciano lived lavishly, with his own

private gym and boxing ring. He was described by those who knew him as

gentlemanly, but reclusive and cunning. On

the four lowest floors were peep shows, X-rated films for a quarter, adult

books, and live sex acts too lurid to be described in print; whatever his

clientele wanted, they got. Yet

everything was just barely within the law, so that the local authorities were

never able to arrest him. (When a

building of his collapsed in Philadelphia, on the other hand, he had to pay $27

million in damages.) Who or what

occupied the other five floors of the Show World site I haven’t ascertained;

they certainly enjoyed some lively neighbors.

By the mid-1990s, when 42nd Street was being

ruthlessly Disneyized and made family-friendly, Mr. Basciano still owned about

a dozen sex shops and employed 400 people.

When, late in that decade, his properties were condemned for new office

buildings and refurbished entertainment venues, he reaped a windfall of $14

million. Show World Center survived,

albeit in a sanitized form, but the tide of decency prevailed, and the McDonald’s

of sex closed in 2016, its real estate value bound to net Mr. Basciano or his

estate another windfall of millions. He

died in Manhattan on May 1, 2017, at age 91.

Museum founder. If you’re an avid collector, what do you

do with your 14 Christopher Woods, 4 Bacons, 10 Warhols, and 34 Renaissance and

Baroque bronzes? Just look at them and

marvel, one would think. But what if you

have quantities of art in storage and want others to see it, too? Donate the stuff? Maybe.

But why not open your own museum instead?

Such was the decision of J. Tomilson Hill, whose private

gallery is slated to open in the fall of 2017 in a two-story space on West 24th

Street in Chelsea, inside a new condominium building named the

Getty. Born and raised in New York,

where he was visiting museums at an early age, Mr. Hill attended Harvard

College and Business School and is now the billionaire vice chairman of a private

equity firm. His new gallery will have

free admission and feature his own collection, valued at over $800 million,

which includes both modern works and old masters, art that he especially wants

to share with students in the city’s schools.

His Upper East Side apartment is likewise crammed with art, as are his

residences in East Hampton, Paris, and Telluride, Colorado. He may jet about the world, but wherever he

has a pied-à-terre, there are sixteenth-century bronzes or Cy Twombly’s massive

graffiti-like scribblings to make him feel at home. He knows artists and curators, but has no art

adviser, spends hours reading and thinking about art, makes his own decisions

and his own mistakes, though his wife has veto power over those decisions. “I’ve got all these ideas,” he says of the

exhibits he wants to do. “Now I’ve got

to find a curator to say, ‘You’re out of your mind.’ ”

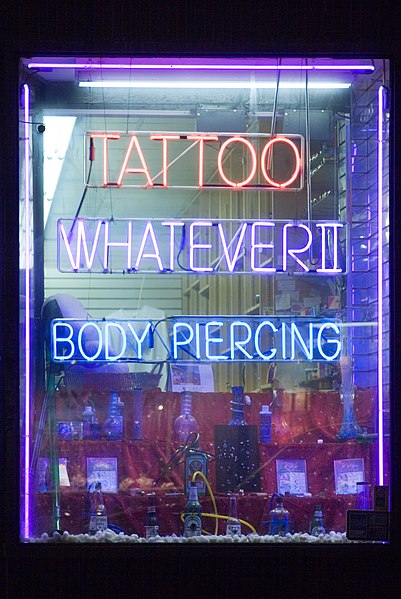

Tattoo artist. Is our skin a blank canvas waiting to be

colored, drawn, or stained on? The

answer is yes, if you’re a tattoo artist or one of their patrons. A worldwide phenomenon going back to primitive

times, tattoos have been thought to heal or protect, or have served to indicate

social affiliation or adulthood. That’s

interesting, but personally I feel no need to flout any such message to the world,

and can’t help but think that any but the smallest and most discreet of them is

tribal, primitive, and grotesque, especially when I see half a torso covered

over with these cunningly contrived graffiti.

This opinion of course marks me as a square, uncool, and hopelessly out

of it, a classification that I gladly accept, even though the New York

Historical Society is now offering an exhibit entitled “Tattooed New York.”

|

| Bartender in a New York gay bar. JoeInQueens |

In nineteenth-century New York tattoos were mostly confined

to seamen, a class apart, though young men of good stock often in their youth went

to sea; a favorite tattoo subject, needless to say, was women, and the more

unclothed the better, this being the only female companionship available for

long months at sea. And during the Civil

War soldiers had their names tattooed, so they could be identified if slain in

battle. But in peacetime no lady or

gentleman of the brownstone-dwelling middle class would think of such a painful

and barbaric display.

|

| Jorge Royan |

By the twentieth century tattooing had evolved into a

complex art form with ink and watercolor designs that had achieved a degree of

acceptance. Most tattoo artists worked

in cramped booths in local barber shops in the Chatham Square area of

Manhattan, tattooing day laborers and tourists who went “slumming” on the

nearby Bowery. When Social Security was

initiated in the 1930s, people who had trouble remembering their numbers had

them tattooed onto their skin. But most

tattoo parlors had as neighbors the saloons and flophouses of the Bowery,

sanctuaries for the desperate, the drunk, and the defeated, which did little to

enhance their image. Then, in 1961, with

a world’s fair looming in the city, the Health Department decreed that

tattooing was the cause of a hepatitis outbreak and got it declared

illegal. But the trade persisted, albeit

by night in apartments and basements. It

thrived in the rebellious 1960s and the punk wave of the 1980s, and finally, in

1997, the ban was lifted, and the underground art became, in some circles, all

the rage. Now considered an art form,

tattooing invaded the galleries and finally even the museums, which brings us

to the exhibit at the New York Historical Society; how much more “in,” more

mainstream can you get?

|

| Here's how it's done. Eneas De Troya |

Today there are tattoo parlors all over the five boroughs,

and they often specialize. Some do cartoons,

others offer Japanese or Polynesian designs, or skulls, psychedelic patterns,

monster heads, birds of paradise, crosses, and of course the inevitable and

time-sanctioned Old Glory. Depending on

your choice of tattoos, you can come off as sweet and soft, weird, funny,

patriotic, menacing, or defiant. As for

the tattoo artists themselves, photos show gentle old men in T-shirts, bearded

machos, bespectacled Asians, and females with bold red lips and fiercely

mascaraed eyes, the arms of all of them, and sometimes the legs as well, richly

and imaginatively adorned. So if you

want to be “modified,” to undergo change and adventure, Bang Bang and Sweet Sue

and Megan Massacre are waiting for you.

Some of them even take walk-ins and a few, to conciliate vegans, use

animal-free inks. The price? $100 and up.

Sometimes way, way up.

Cemetery

archivist. Yes, we’ve done

archivists already, but really just one, and she was a hotel archivist. But cemeteries – especially the old ones –

have more than the dear departed on hand, so they need archivists, too. Take Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn, which

dates from 1838, and through whose broad manicured lawns and noble monuments I once

treaded long ago, while doing research for a biography. Today, in an office near the imposing Gothic

Revival gatehouse the archivist, Anthony M. Cucchiara, guards treasures

retrieved from a boiler room and garbage heaps and now displayed in glass cases

or stacked in piles waiting to be sorted.

There are mausoleum keys; photos and filmstrips of the deeased; a ledger

recording deaths from scarlet fever, dysentery, and mania in the 1840s; and an

1853 letter from President Millard Fillmore declining an invitation to the

inauguration of a statue in the cemetery.

Queries come in from researchers all over the world, and Mr. Cucchiara

is there to answer them. He finds

preserving documents and making them accessible extremely rewarding. “It’s fun to bring them to life,” he says,

ever ready even in these circumstances to elicit a smile.

Forensic pathologist. You work in a long blue monkey suit, gloved,

a white cap on your head, and a blue mask over your nose and mouth. Surrounding you are your colleagues,

similarly robed, gloved, capped, and masked, and close by is your toolbox

containing knives, forceps, scalpels, and scissors. You and your colleagues cluster around a

subject on a gurney who is mottled green from decomposition. You cut into the torso; a greenish fluid

oozes out. You reach both hands into the

body, search for the liver, can’t find it; your gloves drip. You crack open the chest with clippers,

remove the heart and the lungs. A

whirling saw opens the skull so you can reach in and lift out the brain. When you are done, you go on to the next

subject, and then the next and the next.

Such is the work of a forensic pathologist in a city program

training medical examiners, the officials who perform autopsies on deceased

persons whose deaths are sudden or suspicious, or result from crimes,

accidents, or suicides. It is an

occupation in great demand throughout the country, and New York City, where

every conceivable kind of death can be encountered, is a renowned training

ground for the profession.

|

| Examining a digitized body. This way it's less messy. Infovalley |

Your day starts at 8 a.m. in the drab building at 520 First

Avenue that houses the Office of Chief

Medical Examiner, where you present case histories to senior medical examiners,

forensic anthropologists, police detectives, and medical students. Then you check the body bags in the mortuary,

and by 9:30 a.m. you’re in the autopsy room getting started on your first case

of the day. By afternoon, after seeing

to at least three cases, you reconvene with the other trainees to report your

findings. Then you go to the fellows’

room to draft a report for each autopsy, following which you might order lab

tests, interview relatives, and consider other evidence before closing a case. Seeing the relatives can be disturbing; some

trainees can’t help at times but weep.

But others derive comfort from the thought that they are the last person

to care for the deceased, bridging their death and life. Obviously it’s not an occupation for the

squeamish; you wouldn’t be in it if you didn’t think it important, and if what

you see everyday put you off. In a city

like New York, it’s absolutely necessary and always will be, which in itself is

some kind of consolation. And it doesn’t

hurt that it pays well, too. On this

happy note, I’ll conclude.

Source notes:

For this post I am again indebted to articles in the New York Times:

Sam Roberts, “Richard

Basciano Dies at 91; Times Square Sultan of Smut” (May 7, 2017).

Robin Pogrebin, “A

Billionaire Builds His Passion Into a Museum” (July 29, 2016).

Holland Cotter, “Ink: How It

Got Under New York’s Thick Skin”

(February 3, 2017).

Eve M. Kahn, “A Brooklyn

Cemetery Is a Resting Place Rich in History” (July 15, 2016).

Winnie Hu, “Learning to Speak

for the Dead” (June 12, 2016).

* * * * *

BROWDERBOOKS: No Place for Normal: New York / Stories from the Most Exciting City in the World, my selection of posts from this blog, has received these awards: the Tenth Annual National Indie Excellence Award for Regional Non-Fiction; first place in the Travel category of the 2015-2016 Reader Views Literary Awards; and Honorable Mention in the Culture category of the Eric Hoffer Book Awards for 2016. For the Reader Views review by Sheri Hoyte, go here. As always, the book is available from Amazon and Barnes & Noble.

|

The Pleasuring of Men (Gival Press, 2011), the first novel in the Metropolis series, tells the story of a young male prostitute in the late 1860s in New York who falls in love with his most difficult client It is likewise available from Amazon and Barnes & Noble.

Coming soon: Maybe a post on BookCon 2017, where I and 25,000 attendees are right now colliding. Maybe one post on exhibitors and another on attendees. Some wild stuff is happening.

© 2017 Clifford Browder