When not rescuing corporations and governments or making the

national character more Christlike (see the previous post), J.P. Morgan was

traveling abroad and adding to his collections.

Having little interest in art, his wife said he would buy anything from

a pyramid to Mary Magdalene’s tooth. By

now they had drifted apart, she preferring a quiet life and plain living,

whereas he wanted an exciting life in the company of a host of friends. Nor did it help that both were subject to

periodic depression. In his frequent

travels he enjoyed the company of handsome, self-possessed younger women who

shared his love of society and self-indulged pleasures – women, in other words,

very unlike his wife, whom he usually lodged on the other side of the ocean, or

in a spa in France while he hobnobbed with affluent friends on his yacht in the

Mediterranean.

In another age divorce might have been an option, but not in

this late Victorian era. There were

those among the rich who did divorce, but disgrace and ostracism followed. For Morgan, a pillar of the Anglican Church

and an esteemed member of countless boards and clubs, it was out of the

question, but how far his friendships with other women went can be debated. Morgan’s attitude in such matters is well

expressed by a story recounted by one of his biographers. A young partner of his having been caught in

an adulterous affair, Morgan summoned him into his office and upbraided

him. “But sir,” the young man protested,

“you and the other partners do the same thing yourselves behind closed doors.” “Young man,” said Morgan, eyes ablaze, “that

is what doors are for!” So Morgan

endorsed the eleventh and supreme commandment: Thou shalt not be found out.

But found out he may have been, for the gossip sheet Town Topics of July 1895 asked, “Why

does the wife of a certain wealthy man always go to Europe about the same time

he returns home, and vice versa?” Mentioned on the preceding page were Mr. and Mrs.

Pierpont Morgan and, in a separate article, Edith Randolph, a widow whom

Pierpont Morgan had been seeing a lot of at the time. The editor of Town Topics, Colonel William D’Alton Mann, was in the habit of

reporting illicit behavior by an unnamed individual, while naming the

transgressor in a paragraph nearby; alarmed, the offender was usually

forthcoming with cash to buy Dalton’s silence.

When Dalton was sued for libel in 1906, the names of his victims and the

amounts they paid came out, including Pierpont Morgan, $2500. The defendant insisted that this and other such

sums were simply unrepaid loans, but admitted approaching numerous men of

wealth to ask them to “accommodate” him so as to avoid future criticism on his

part. Still, $2500 was a modest bit of accommodation,

compared to the $25,000 forked over by William K. Vanderbilt, a grandson of

Cornelius Vanderbilt, for who knows what transgressions. As for the lady in question, Mrs. Randolph,

in 1896 she remarried, thus removing herself from the purview of Pierpont

Morgan, who found solace in the company of another younger woman encumbered

with a husband and two children, but not with too strict a concept of

propriety. As for Colonel Mann, he

himself escaped prison, but his agent was convicted of extortion, and Dalton’s

extortion business was thoroughly exposed.

As long as business-friendly William McKinley was president,

Morgan and the business community breathed easy, for they knew what to

expect. But when McKinley was

assassinated by an anarchist in 1901, he was succeeded by Vice President

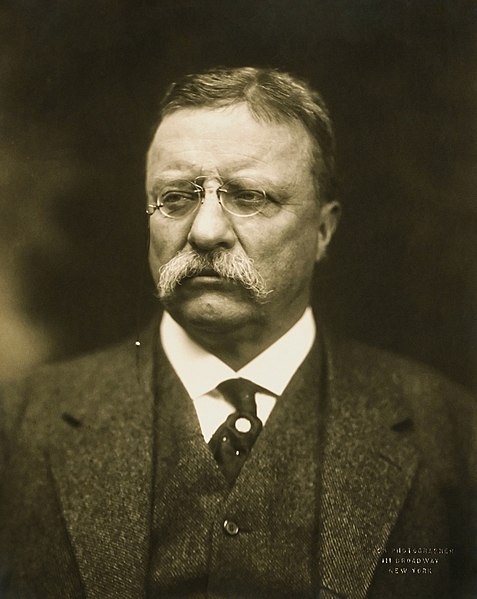

Theodore Roosevelt, a rough-riding cowboy with novel and alarmingly progressive

ideas. Roosevelt had become a national

hero by charging up San Juan Hill in the recent war with Spain, and now he had

charged right into the White House, and for the business community this meant

trouble.

|

| Another moustached powerhouse, but this one was in the White House. |

Sure enough, in 1902, making use of the rarely enforced

Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890, the president filed suit against the Northern

Securities Company, a railroad holding company organized a year earlier by

Morgan and the presidents of three railroads so as to limit ruinous

competition. The company was accused of

illegal restraint of trade.

Morgan was

stunned. Why hadn’t the president

consulted him? He hurried to Washington

to have a talk with Roosevelt. “If we

have done anything wrong,” he told the president, “send your man to my man and

they can fix it up.” Replied Roosevelt,

“That can’t be done.” Morgan was stunned

again. This wasn’t how gentlemen did

business. You didn’t make your

differences public, you worked them out in private. But this Rough Rider in the White House,

though from an old New York family, had different ideas on the matter – wild

ideas, and dangerous. He wanted to

subject businessmen – the very men who were making the country prosperous and a

leader among nations – to the rule of government!

The case against Northern Securities went all the way to the

Supreme Court, which in 1904 ruled that the company was an illegal combination

and would have to be dissolved, which it promptly was. Morgan had lost, Roosevelt had won. But this didn’t make them irreconcilable

foes, for each found the other useful – yet another example of how power

respects power. Roosevelt began

distinguishing between “good” and “bad” trusts, put Morgan’s in the “good”

category, and consulted the banker on matters of finance – the kind of behind-the-scenes

conferring that old J.P. infinitely preferred.

But more trouble was coming.

Seemingly out of nowhere, October 1907 brought a rude shock to Morgan

and the nation, when a speculator’s misguided attempt to corner the stock of

the United Copper Company failed, sending the company’s stock plunging. Then the speculator’s brokerage house failed,

and runs began on banks associated with him and his confederates. Other banks tightened up on loans, interest

rates on loans to brokers soared, stock prices plummeted, and more banks

failed. Suddenly the whole financial system looked shaky, and

the Panic of 1907 was well under way.

All eyes turned to J.P. Morgan, the city’s most prestigious and

most well-connected financier, who had squelched financial crises before. Out of the city attending an Episcopal

convention in Richmond, Virginia, he received wires and messengers from his

partners, who warned him not to rush back immediately, since that would only

heighten the sense of panic. As soon as

the convention ended, Morgan hurried back to the city and summoned a host of

bank and trust company presidents to his library on 36th Street,

where he and his associates scanned the books of endangered corporations and

decided which ones could be saved. Secretary

of the Treasury Cortelyou came from Washington to help, and John D. Rockefeller

put up $10 million. From then on the

Morgan Library, a high-ceilinged treasure house of Gutenberg Bibles and

Renaissance bronzes, would be the scene of one emergency meeting after another.

On October 24, when stock prices continued to plunge, and

the Stock Exchange threatened to close early, Morgan, puffing on a cigar,

sleep-deprived and fighting off a cold, summoned the presidents of the city’s

banks to his office, and told them that as many as 50 brokerage houses would

fail unless they raised $25 million in ten minutes. The money was raised, disaster was

averted. When the panic resumed on the

following day, Morgan got the banks to pledge more money to keep the exchange

open, and brokers on the exchange floor cheered.

This calmed the panic on Wall Street, but on October 28 the

mayor of New York came to Morgan

and informed him in confidence that the city was verging on bankruptcy,

whereupon Morgan and two allies quietly agreed to buy $30 million of city bonds. And when yet another major brokerage house

verged on failure, Morgan summoned a group of executives to yet another

emergency meeting at his library and averted yet another collapse.

But the crisis was far from over, for the financial system still looked shaky. When runs threatened two more trust companies

whose failure could not be risked, Morgan summoned some 50 bank and trust

company presidents to his library on Friday, November 2, locked them in his

sumptuous study, pocketed the key, and in what turned out to be an all-night session,

demanded that they pool their resources to make a loan of $25 million to save

the companies. The financiers at first

held back, but who could withstand Morgan’s imperious will and his piercing

eyes, meeting whose gaze was said to be like looking into the lights of an

oncoming express train? Glaring

fiercely, he held out a pen, gestured toward the relevant document, and said to

one of them, “There’s the place, and here’s a pen. Sign!”

The banker did, and so did all the others, one by one. Only when he had obtained the last signature,

did Morgan unlock the door at 4:45 a.m. on Sunday and let them wearily depart.

But that was not the end of it. The approval of President Roosevelt was

necessary, since part of the proposed solution involved U.S. Steel’s acquiring

a troubled steel producer, so two bankers had rushed to Washington to see him. But would the trust-busting president approve

a deal allowing the biggest corporation in the world to get even bigger – a

transaction that would arouse public criticism and invite antitrust

proceedings? Roosevelt heard them out,

grasped the situation, and gave his assent.

Minutes before the Stock Exchange opened on Monday morning, November 4,

a phone call from Washington reported the president’s decision -- news that,

when relayed to the exchange, immediately restored confidence. After two weeks of panic the crisis was finally

resolved, and for the first time in days the exhausted old man got a good

night’s sleep.

The panic had affected the whole nation. Throughout the country bankruptcies

multiplied, production fell, unemployment rose, and immigration plunged. When my maternal grandfather, a respected

judge in Indianapolis, Indiana, suffered financial reverses, he had his eldest

child, my mother, become a schoolteacher so as to bring in more money. Barely eighteen, she taught in a little

one-room rural schoolhouse for two years, a maturing experience made necessary

by mysterious happenings on Wall Street in distant New York. But not all families coped as well; many were

ruined.

In the wake of the panic J.P. Morgan was seen as a hero by

many, but not by all, and suspicions arose at once. Had the panic been engineered by the banks so

they could profit from it? Had Morgan

(who in fact had lost $21 million in the panic) taken advantage of it? And should the safety of the entire financial

system depend on one man, however well-intentioned, and what would happen when

this aging benefactor – if benefactor he was – departed this earth for

celestial climes? Debate raged.

Finally, in 1912, a special House of Representatives

subcommittee, chaired by Representative Pujo of Louisiana, set out to investigate

the “money trust,” the alleged monopoly whereby Morgan and other city bankers

controlled major corporations, railroads, insurance companies, securities

markets, and banks. Morgan of course was

subpoenaed, and his testimony would be the climax of the investigation. Politicians, lawyers, clerks, journalists,

and visitors awaited his arrival with the keenest interest. It would be the

kind of public event that the Napoleon of Wall Street loathed, and an abrupt

change from quietly professing his love at age 75 to Lady Victoria Sackville

earlier that year in England, and sailing with Kaiser Wilhelm in a five-hour

race at the Kiel regatta – a race that they won by twenty seconds, filling the

emperor with joy. Back home from these

diversions, Morgan went to Washington with misgivings.

On December 18, 1912, he showed up at the hearing in a dark

velvet-collared topcoat and the inevitable silk hat, accompanied by his

daughter Louisa and his son Jack, plus partners and lawyers. On that day and the next, in a room crammed

with journalists, photographers, and spectators, the committee’s counsel,

Samuel Untermyer, questioned him at length, establishing that officers of

Morgan’s and four other banks held 341 directorships in 112 U.S. corporations,

with the Morgan partners alone sitting on 72 boards. Some questions Morgan said he couldn’t

answer, and some of his answers seemed

enigmatic, for he and Untermyer were in different worlds, operating under

different assumptions. Asked if he

wanted to control everything, Morgan said clearly enough that he wanted to

control nothing. And when asked if he

was not a large shareholder in another major bank, he replied, “Oh no, only

about a million dollars’ worth,” and was surprised when the spectators laughed.

Finally, in an exchange that would become famous, Untermyer

asked, “Is not commercial credit based primarily upon money or property?”

“No sir,” said Morgan.

“The first thing is character.”

“Before money or property?”

“Before money or property or anything else. Money cannot buy it.”

Saying this, Morgan was quite sincere. In the world of gentlemen bankers, one did

business with people one knew and trusted; character – perceived character –

did indeed count.

Morgan, his family, and friends all thought that he done quite

well before the committee, and much of the press agreed. Two weeks later he left for Egypt with his

daughter Louisa and several friends. He

seemed fine while crossing the Atlantic, but then became agitated and

depressed. On the Nile he fell into a

delusional depression, had bad dreams, spoke of conspiracies and subpoenas and

contempt of court, and told Louisa that the country was going to ruin, that his

whole life work was going for naught. As

the party retreated to Cairo and then to the Grand Hotel in Rome, word of his

condition got out, and messages of concern came from the pope, the king of

Italy, and the Kaiser. Flocking also to

the hotel were art dealers and amateurs with bundles of items to sell to the

great collector. Morgan rallied, made

some jaunts into the city, but then declined, became delirious, and died in his

sleep on March 31, 1913, just shy of his 76th birthday, the cause of

death never ascertained.

Flags on Wall Street immediately flew at half mast, and on

April 14 the Stock Exchange closed for two hours while his body passed through

New York City on its way to burial in Hartford.

The funeral at St. George’s Church in Manhattan displayed flowers from

the Kaiser, the government of France, and the king of Italy; 1500 attended,

with thousands more outside. There were

memorial services in London and Paris as well.

The total value of his estate was about $80 million (well

over $230 million in 2016 dollars); most of it went to his son, with generous

bequests to family and friends. His son

put most of his art collection on exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art,

and subsequently sold some of it to various collectors, but donated many works

to the Met.

Was John Pierpont Morgan’s death hastened by the Pujo

committee’s treatment of him, and public skepticism about the values he held

dear? Probably. The world was changing, and Morgan was too

old and too fixed in his ways to change.

The era of the gentleman banker had passed. In 2013 Congress created the Federal Reserve

System to provide central control of the monetary system, issue currency, and

create a stable financial system, which, with its powers expanded, it does to

this day. It took a complex system of

twelve regional banks, each with branches and a board of directors, and a

seven-member governing board appointed by the president, to fill the void left

by the death of J.P. Morgan.

I confess I'm rather taken with old J.P. and his naiveté -- yes, naiveté! -- in thinking that gentlemen bankers of good character could still handle the affairs of the nation, and that in creating monopolies he had America's best interests at heart. Both eulogists and critics of the man were correct. John Pierpont Morgan was both a monopolist and a savior of the nation, an autocrat and a benefactor. He truly believed that the wealth he had accumulated should be used for the good of the nation

-- richesse oblige -- and acted accordingly. Luckily, he died before the outbreak of World War I. Having been a friend of both the king of England and the emperor of Germany, he could never have adjusted to a war-ravaged Europe and the catastrophic end of the world he had known. He believed in order; war brought chaos.

I confess I'm rather taken with old J.P. and his naiveté -- yes, naiveté! -- in thinking that gentlemen bankers of good character could still handle the affairs of the nation, and that in creating monopolies he had America's best interests at heart. Both eulogists and critics of the man were correct. John Pierpont Morgan was both a monopolist and a savior of the nation, an autocrat and a benefactor. He truly believed that the wealth he had accumulated should be used for the good of the nation

-- richesse oblige -- and acted accordingly. Luckily, he died before the outbreak of World War I. Having been a friend of both the king of England and the emperor of Germany, he could never have adjusted to a war-ravaged Europe and the catastrophic end of the world he had known. He believed in order; war brought chaos.

Source note: For information in this post, as in the

preceding one, I am indebted to Jean Strouse’s magisterial biography, Morgan: American Financier (Random

House, 1999).

* * * * * *

My poems: For five acceptable poems, click here and scroll down. To avoid five terrible poems, don't click here. For my poem "The Other," inspired by the Orlando massacre, click here.

My books: No Place for Normal: New York / Stories from the Most Exciting City in the World, my selection of posts from this blog, has received these awards: the Tenth Annual National Indie Excellence Award for Regional Non-Fiction; first place in the Travel category of the 2015-2016 Reader Views Literary Awards; and Honorable Mention in the Culture category of the Eric Hoffer Book Awards for 2016. For the Reader Views review by Sheri Hoyte, go here. As always, the book is available from Amazon and Barnes & Noble.

|

The Pleasuring of Men (Gival Press, 2011), my historical novel about a young male prostitute in the late 1860s in New York who falls in love with his most difficult client, is likewise available from Amazon and Barnes & Noble.

Coming soon: Katahdin: How, even with a governor against it, a nonprofit gets things done.

© 2016 Clifford Browder