New York is in perpetual flux and always has been. This post is about buildings that change, buildings that undergo amazing metamorphoses. We'll start back in the nineteenth century.

Grand Central Hotel

The slender man, wearing an

elegant gray overcoat, top hat, and polished boots, stood at the top of the hotel

stairs, revolver in hand, eyeing the top-hatted fat man in a cloak halfway up

the stairs.

“I’ve got you now,” said the man at the

top of the stairs; he fired one shot, then another.

The fat man, a perfect target at

point-blank range, staggered, grasped a handrail, managed not to fall. “For God’s sake,” he shouted, “will anybody

save me?”

The slender man fled into the hotel, where

he was soon apprehended. Alarmed by the

sound of the shots, hotel employees came running, helped the wounded man up the

stairs and into a vacant room. Word of

the shooting spread like fire through the city, doctors flocked, newspapers

stopped their presses and prepared a story.

The fat man lasted the night, then died.

|

| A bellhop witnessed the shooting. From Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper. |

Such was the fatal shooting, on January 6,

1872, of Colonel James Fisk, Jr., robber baron, impresario, and commander of

the Ninth Regiment of the New York National Guard, who, after President Grant,

was the most reported-on man in the nation.

The shooting was all about the charms of Miss Helen Josephine Mansfield,

Fisk’s former mistress and the present inamorata of the assailant, Edward S.

Stokes, a handsome but impecunious man-about-town whose attempts to get money

out of Fisk had proved fruitless. Fisk

was given an elaborate military funeral and shipped off to his home town of

Brattleboro, Vermont; Miss Mansfield disappeared; and Stokes survived two

trials for murder, was convicted at a third of manslaughter, served four gentle

years at Sing Sing, and was released.

The point of this story is not to tell

once again the dramatic end of Colonel Fisk, which I recounted in another post

long ago, but to situate the crime in the Grand Central Hotel and show how,

with time, that hotel’s fortunes changed.

In 1870 it had opened on Broadway between West Third and Bond Streets,

an eight-story, 400-room hostelry in Second Empire style, with the mansard

roofs then fashionable. One of the

largest in the world at the time, it had three elegant dining rooms and

sumptuous Gilded Age furnishings. Fisk

had called there because he was visiting the family of a deceased friend

who were living there in comfort, thanks to his largesse.

|

| The Broadway Central Hotel in 1893. |

In the years that followed, the hotel

witnessed elegant society weddings, other fashionable events, and an occasional

murder or suicide, but nothing so dramatic and headline-grabbing as the affair

of January 6, 1872. But times and

neighborhoods change, owner followed owner, financial difficulties arose, and

by the late 1960s the hotel, now known as the Broadway Central Hotel, had

become one of the city’s largest welfare hotels, with its share of crime, drug

use, and prostitution. Gone was the glamour

of the Gilded Age, but in an attempt to spark it up, six theaters called the

Mercer Arts Center moved in, and it was renamed the University Hotel. But residents reported cracks and sagging

walls.

Early on August 3, 1973, those living

there heard “bongs,” “tings,” and “groans,” and everywhere saw plaster falling

in the building. By late afternoon most

of the 300 residents had been evacuated.

Then, at 5:10 p.m., a huge section of the building collapsed in a cloud

of smoke, bringing a vast pile of tangled wreckage and rubble down on the

street. As firemen later sorted through

the rubble, four bodies were found. The

rest of the hotel was torn down and removed, including the ill-fated Mercer Arts Center theaters. Housing for New York

University Law School students stands on the site today.

Not every old building goes out with a

bang, but startling metamorphoses

occur. Long ago, in some printed source

I can no longer locate, I saw a mid-nineteenth-century photograph of a church

turned into a stable. I have never

forgotten the shock at seeing what had obviously once been a house of God

abruptly converted into a house of horses, with teams constantly going in and out those

once sacred portals. And

I’m sure that the aroma of piety had similarly yielded to the smell of

manure. So let’s have a look at some

other buildings that have changed over time.

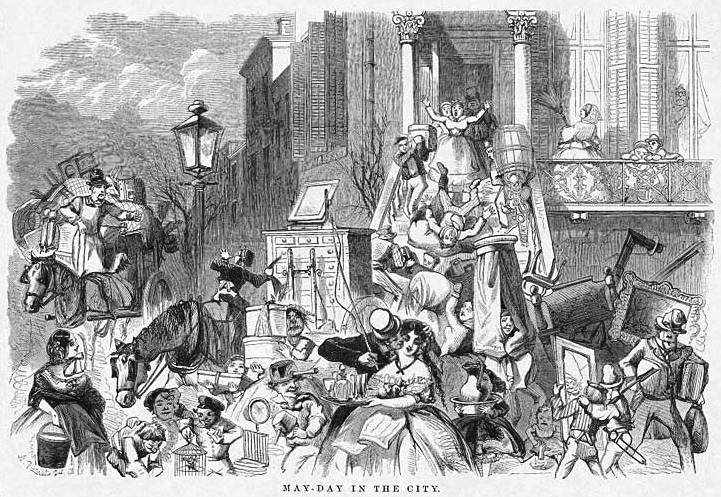

May 1: moving day

In nineteenth-century New York

those changes occurred massively, and convulsively, on May 1 of each year, when

both residential and commercial leases expired citywide. On that day cartmen could charge triple their

usual prices and were reserved weeks in advance. The streets became a jumble of carts and

wagons, with cartmen shrieking oaths as they transported people’s furnishings, often as not trading fisticuffs with other cartmen doing the same. A sign announcing SOAP & CANDLE FACTORY

might come down, to be replaced by BOOTS & SHOES, while a family’s precious

pianoforte, the showpiece of the parlor, was carried on a cart with special

springs, bound for a more sumptuous brownstone fronted by a steep stoop often

fatal to bulky but delicate objects in transit.

A jewelry store might become a lager beer saloon; an oyster cellar, a

salesroom displaying fancy coffins; and a young ladies seminary, a house of ill

repute. On May 1 anything could happen

and often did.

|

| Moving day, May 1, 1856. Be sure to notice the details; they say a lot. |

Carriage houses

One of the most surprising

metamorphoses, over time, has been the transformation of carriage houses into highly coveted and

high-priced housing. One sees them all

over the West Village, where I live, their wide entrances meant to accommodate

carriages but now changed into elegant residential doorways. Once these little structures housed carriages

and teams of horses, with the coachman and his family lodged snugly on a floor

above, while the employer’s family occupied a spacious Greek Revival or

brownstone mansion on a nearby but more fashionable street. Occasionally, as at 271 West 10th

Street, one sees a metal hayloft hoist projecting from a floor above, originally

installed to lift heavy bales of hay up to a second story, or in this case, to

a third story, since the 1911 building once lodged a construction firm’s horses

on the first and second floors, and a hay loft on the third. And how did the horses get up to the second

floor? By a ramp, of course. And what price does this modest little

three-floor structure fetch today? $17.2

million.

Bayview Correction Facility

Another building with a

history is the Bayview Correction Facility, a notorious women’s prison at West

20th Street and Eleventh Avenue.

In 1931 the eight-story red-brick Art Deco structure had opened in the

rough West Chelsea neighborhood as the Seamen’s House, a Y.M.C.A. accommodating some 250

merchant seamen whose ships docked at nearby piers. As New York declined as a port, it ceased to

serve that function and in 1967 was sold to the city, which turned it into a

drug-treatment center. But the 1973

Rockefeller drug laws imposed long prison sentences instead of rehab on

offenders, so in 1974 the building became a prison, and in 1978 a women-only

facility that was soon plagued with reports of staff sexual misconduct,

unsanitary conditions, and poor medical care.

In other words, it rivaled the Women’s House of Detention, another

scandal-ridden facility that loomed like a dreary Bastille in the heart of

Greenwich Village, whose genteel residents (myself included) were scandalized by the often

obscene exchanges of inmates with their friends on the street below. And just as that Bastille was in time

demolished to the satisfaction of almost all, so the Bayview, which closed as a

prison in 2012 following flooding caused by Hurricane Sandy, has now found

itself besieged on all sides by gentrification and likewise a candidate for

demolition.

Surrounding the ex-prison today are art

galleries, an entertainment complex just across the street, and a shiny new

condominium. But the Bayview, for all

its sordid past, had been designed by the same designers responsible for that

marvel of Art Deco, the Empire State Building, and therefore, though not

landmarked, seemed worth saving. The

neighbors feared yet another luxury housing development, but a happy compromise

has been found: it will be gutted and converted into offices to be rented out

primarily to nonprofits providing services for women. And to spice it up, there will be landscaped

terraces and an art gallery, and a refurbished swimming pool lined with mosaics

of fish, and a chapel with stained glass windows showing seafaring scenes. (Those windows won’t be Chartres, but let’s

not quibble.) In addition, a six-story

annex added in 1950 will be demolished and replaced with a glass-walled atrium. So how trendy can you get? All in all, the neighbors are delighted … and

relieved.

|

| Knox Martin's "Venus." |

Covering the entire south wall of the

building, by the way, is an abstract mural entitled “Venus” by artist Knox

Martin, which dates from 1970, prior to the Rockefeller drug laws and long

predating gentrification, back in a time when art for the masses was "in." It’s a huge affair, an abstraction with big

patches of red, blue, green, and pink, but what it has to do with Venus, philistine that I am, I can’t imagine. Let’s

just say it ain’t Botticelli. Commercial

interests have hankered for the space, then visible from miles away, but the

fastidious Correctional Services didn’t want Venus covered over with ads for

jeans or beer. And today? The mural is almost entirely obscured by

architect Jean Nouvel’s “vision machine,” a super modern 23-story residential

tower at 100 Eleventh Avenue completed in 2010. So vision trumps Venus; so it goes.

Metro Theater

Few

buildings have undergone more dramatic and often depressing metamorphoses than

old movie theaters built in another age.

The Metro Theater on Upper Broadway between 99th and 100th Streets

opened as the Midtown (a misnomer) in 1933, in the pit of the Depression and

long before television, back when movies were one of the few recreations accessible

to people on a budget. An Art Deco gem

with a terra-cotta façade, it featured, above the marquee, a medallion,

illuminated at night, with two female figures back-to-back, holding the masks

of tragedy and comedy. Needless to say,

such a fancy façade, not to mention the elaborate interior, announced a theater

showing first-run films, a movie theater at the top of its kind. Adaptable, in the 1950s and 1960s it showed

foreign films and other non-mainstream fare – just the sort of films that I was

then seeking out in small art theaters in Greenwich Village, having lost

interest in the concoctions of Hollywood. By

the 1970s, with television co-opting the film-watching audience, the theater

had stooped to showing second-run films and finally, like so many desperate

movie houses struggling to survive, pure porn.

(As if porn could be “pure.”) Reviving

as an art house in the 1980s, with a name change from Midtown to Metro, it

showed first-run films again in the 1990s, before decline resumed, forcing it

to close in 2004.

Abandoned since then, it became a

shuttered eyesore in a neighborhood again on the rise. Having a façade landmarked in 1989, the Metro

posed a problem: what to do with an aging movie house, its interior long since

gutted, that had become an eyesore, a structure too small to accommodate the

multiplex theater of today. To further complicate the matter, the theater's lack of windows, and its jutting landmarked

marquee casting shadows on the entryway, made it undesirable as retail

space. The Metro was now a once

glamorous lady desperate to age gracefully, but to whom the years had not been

kind.

Since the theater’s closing, numerous

deals have been announced. It was going

to become an Urban Outfitters clothing store, the home of a nonprofit arts

education group, a member of the Alamo Drafthouse Cinema chain, serving beer. But year after year the marquee posted the

phone numbers of real estate dealers hoping to find a tenant, and no tenant

appeared. Many neighbors hoped it could

house a cultural institution of some sort, but this was not to be. Finally, after a year of negotiations, a deal

was announced last October: the Metro will become a Planet Fitness gym. Not even a trendy high-cost gym, but a gym

costing only $10 a month. “At least it

isn’t a Duane Reade,” the local city councilman remarked. What the figures above the marquee, with

their masks of comedy and tragedy, think of this dénouement, I dare not venture

to ask. But at least the old Metro is

saved.

American Bible Society Headquarters

For 49 years the American

Bible Society has been headquartered at 1865 Broadway, at the corner of Broadway

and West 61st Street, in Manhattan.

Today, it’s surprising enough to learn that a nondenominational society

founded here in 1816 to print Bibles and ensure their widest possible

distribution has been located in congested, secular New York, in a 12-story

building towering above the hectic, converging traffic of nearby Columbus Circle,

crossing which on foot, even in a marked crossway and with the light, makes me

nervous. But there it is, or rather,

there it has been since 1966, when it moved from its previous home on chic Park

Avenue, another surprising address. But

today the Society seems hardly at home in this neighborhood of cloud-scratching

super luxury high-rises and the tenants they attract.

|

| The Bible Society building in 2008. |

The building itself is 1966 functional late

Modernist, nothing godly or sanctified about it, but of course it was an

office, not a place of worship. One observer

has suggested that the twelve deep recesses of its façade, one at each story,

might hint of the twelve tribes of Israel or the Twelve Apostles, but let’s not

push it; it was a secular building with a saintly purpose. Back in its heyday, and the heyday of

Protestant missionary work worldwide, the Society by 1893 had printed

56,926,771 Bibles and helped in the translation, printing, or distribution of

Scriptures in 95 languages and dialects the world over. Needless to say, times have changed; it

stopped printing Bibles in 1922, and moved from one site to another before

settling down in Columbus Circle. And if

that structure fails to inspire, it’s worth noting that it was decidedly

innovative, being the first in the city to be built with load-bearing exterior

walls made of pre-cast concrete panels, unlike the usual soulless high-rises of

the time, with heavy interior steel frames and diaphanous glass skins. (Don’t let “diaphanous” mislead you; most of

them are dull indeed to look at.)

And today?

The Bible Society, citing the building’s need of repairs and the high

cost of doing business in New York, is moving to Philadelphia; in fact, it has

moved already. And the building itself,

not landmarked, will it be refurbished and preserved? No way; sold to a developer for $300 million,

it has a date with the wrecking ball. I

doubt if tears will be shed, but replacing it will be a sleek 40-story

glass-and-masonry tower with ground-floor retail space along Broadway and luxury apartments

above, including, I’m sure, a super luxury penthouse: a concoction that may or

may not inspire rhapsodies of praise. As

always in this city, flux.

One casualty of the change is the Museum

of Biblical Art, also housed in the building, which, just after attracting

record crowds to an exhibition featuring the Renaissance sculptor Donatello,

has also had to close. Likewise affected

was a bronze sculpture by Lincoln Fox installed in front of 1865 Broadway in 2007;

entitled “Invitation to Pray,” it showed, seated on a bench, a life-size

Jeremiah Lanphier, who founded the Fulton Street prayer meeting in 1857, a year

of financial convulsion that drove some to despair and others to religion. Leaving plenty of room for others on the

bench, the statue attracted passersby, though less for prayers than

“selfies.” Their online comments include

praise of his shiny bronze clothes, “he looks like he wants company,” and

“ick.” But Jeremiah has not been

demolished, nor will he be moving to The City of Brotherly Love. He now sits in the lobby of King’s College, a

Christian liberal arts college located far downtown at 56 Broadway, another

island of piety in secular New York.

|

| Not exactly Michelangelo, but why quibble? It's been saved. |

BROWDERTHOTS

These are profundities so deep that I hesitate to share them with others. But I'll risk two today:

If these are too much for you, I promise to suppress them in the future.

The book: Many thanks to those of you who have bought it. Still available from Amazon and Barnes & Noble and elsewhere.

Coming soon: Dying alone, the dread of many New Yorkers, and what happens if you do. A tale of hazmat suits, hoarding, X-rays, pranks, and cremains.

These are profundities so deep that I hesitate to share them with others. But I'll risk two today:

A

rose in full bloom

is

a raunchy miracle.

Lilies

are obscene.

Envy

the creators.

Their

navels hiss,

their armpits sing. If these are too much for you, I promise to suppress them in the future.

The book: Many thanks to those of you who have bought it. Still available from Amazon and Barnes & Noble and elsewhere.

Coming soon: Dying alone, the dread of many New Yorkers, and what happens if you do. A tale of hazmat suits, hoarding, X-rays, pranks, and cremains.

©

2015 Clifford Browder

No comments:

Post a Comment