“I

hate Mrs. Brooks!” I announced to several classmates, not in a spirit of

bravado or revolt but simply as a statement of fact. Immediately Daffy Dinwoody, the class tattletale,

rushed to inform the lady in question, she being my first-grade teacher and a

bit of a battleax. The result was a

fifteen-minute lecture on responsibility and respect, barely half of which my

six-year-old mind managed to grasp.

Things quieted down after that, for Mrs. Brooks had her softer moments,

albeit few, and she was simply the fire-breathing dragon guarding the entrance

to a paradise of learning since, once I got past her, the other teachers were

easy to cope with and my grades and spirits soared. I relate this incident simply because,

insofar as I can tell, it was the first time I used “hate” as a verb.

Toward the end of sixth grade my class was

informed that Biff Brady, a much-sought-after school entertainer, would be

hosting the sixth-grade graduation party, and lucky we were to get him. The much-anticipated party took place in the

gym, which should have warned me, since for me, a bespectacled bookworm, the

gym was a scene more of horrors than accomplishments. Biff Brady proved to be a meaty hunk of a man

with a loud voice that commanded and a manner that effused a hearty and blatant

cheer. Not five minutes into the party

he called for quiet and when I babbled on to friends for a moment or two more,

he commanded loudly, “Be quiet, Glasses!”

|

| I was clueless as to what this was all about. |

I hated him. I loathed and detested him, for I had been

called “Four-Eyes” all too often, and in him I sensed a forerunner of the

seventh- and eighth-grade coaches who would torment me, whether by their

attention or their total indifference: beefy, obtuse types with thick necks and

hairy armpits whose physical education classes were physical but hardly

educational, since the coaches spent most of their time doing paperwork in

their office. Occasionally they emerged from

their sanctum to inflict, without preparation of any kind, some new species of

torment such as gymnastics or boxing or wrestling, rather than the usual touch

football (where I could lose myself in the scrimmage, clueless as to what it

was all about) or baseball (all eyes on me as I struck lamentably out or

fumbled a ball in the field). With

hindsight I would say that the hate I felt for these clumsy oafs was not

intense; perhaps it should dismissed as mild but persistent dislike. But they taught me a valuable lesson: Know who the enemy is. From then on, I did.

|

| This I could manage. |

|

| This was a horror. |

An enemy of a different species was Miss Kraus, the

junior high music teacher whose depredations to my psyche were dire. A tight little woman with an acid sense of

humor, she put the weaker pupils in the front rows and the better ones in back

(I was well toward the front), then patrolled the aisles, listening to each

pupil in turn as we chorused lustily together.

Not knowing how to read music and being incapable of singing on key, I

dreaded her approach. If she detected an

off note, she had the culprit – often me – sing the passage alone, subjecting

errors to her dry, mordant wit. She never

used my first name, called me “Browder” or “boy.” Tuesdays and Thursdays were an ordeal for me,

since I had gym and music back-to-back, but it was Miss Kraus who inspired the

keenest fear. Did I hate her? No, but I should have. Fear is the first step toward hate, since

what we fear we inevitably hate. But I

kept my fear to myself, let it stew in my murky depths. I had other bad teachers – a few – but only

Miss Kraus incites my resentment today. She

once told us of getting caught in quicksand where she grew up in Texas, and

ever since I have wondered why, when God put it there for a purpose, that

quicksand didn’t do its job.

|

| If only … Peter O'Connor |

One other individual from my childhood

whom I should have hated was Hector Stevenson, who, playing tough to mask his

own vulnerabilities, constantly challenged me to fight and called me “Sissy!”

when, being a bespectacled wimp of a bookworm, I refused. At these moments he had a surly look, his

upper lip drawn tight, that I came to recognize in bullies. He achieved the ultimate in meanness one

afternoon when, on his way home from school in the company of his little

brother, he socked Billy Simpson in the eye.

I came on the scene just after the incident, with Billy weeping, other

pupils denouncing Hector, and the assailant sauntering off in triumph, having

proven his toughness to his kid brother.

If there was anyone in our class more vulnerable than me, it was Billy

Simpson, a likable and absolutely harmless kid, but an easy mark for Hector,

who was careful never to take on the tougher boys of the class. Hector instilled in me a lifelong hate of

bullies.

The bully whom I encountered daily was my

brother, three years older than me, who once, without provocation, bounced a brick

off my forehead. Probably he meant to

miss me and scare me, but he yielded to an impulse and his aim was far too

good. I ran home screaming, with a huge

swollen lump on my forehead, and they rushed me off for X-rays to see if there

was a fracture (there wasn’t); what my parents did to my brother I don’t know,

but it must have been severe.

Once, just once, I fought back to the

point of frightening my brother. One

afternoon at home, having been constantly harassed, I snatched up a letter

opener and flung it at him. I’d like to

say that it missed him narrowly and lodged itself deep in the wall but a inch

or two from his dear face, but in fact it wasn’t thrown with much force, missed him

widely, and clattered harmlessly to the floor.

But years later, when we were older and calmer, he confessed that it had

scared him at the time. Did I hate

him? No, I was leery of him and made sure

not to provoke him, but for some reason my feelings never achieved the level

and intensity of hate.

So much for the hates and travails of my

childhood, no different, I suspect, from the childhood hates and travails of

most of us. So what today, in my wiser golden years, do I hate? Lots of things:

· Bullies

· Junk mail

· Telemarketing phone calls

· Lists of things to do

· Noise (especially jack hammers)

· Monsanto (above all because of GMO’s)

· Big Pharma (their foul marketing practices, for which

they are constantly paying hefty fines)

· My computer (when it misbehaves)

In short, all the things that

harass my daily living, with bullies, Monsanto, and Big Pharma thrown in. As for telemarketing phone calls, I

especially hate the endlessly repeated recorded messages, several of which I

have received up to 40 or 50 times to date; I hate them for their mindlessness,

their sheer stupidity.

These are significant annoyances, but do

they deserve to be hated, as opposed to disliked or resented? Perhaps not.

Of course there are lots of things to be

hated with a robust, positive hate: injustice, racism, brutality, intolerance –

the list goes on and on. But these are

abstractions, and hating them costs us nothing.

How about people? Is there anyone

living that I hate? But first, what do I

mean by “hate”? Upon reflection I would

say that hate is a settled and persistent enmity that risks becoming vicious

and obsessive. Do I hate with that kind

of hate, the kind that Hitler felt for the Jews, or that Osama Bin Laden felt,

and whose followers still feel, for Americans?

No, not that I can think of. And

when I put the same question to my friend John, he pondered a moment and then

said the same. It takes a lot of energy

to really, truly hate.

I can’t hate public figures with whom I

disagree; I can dislike them intensely, but it doesn’t achieve the status of

hate. The one who comes closest to

inciting hate in me isn’t Baby Bush, whose foreign policies I deplored, for on

a personal level he struck me as rather likable. The one whom I can almost hate – almost -- is

Dick Cheney, the former vice-president under Bush. Why him?

Because he’s always managed to have his finger in every pie, public or private, and in the

process reaped a fortune. Bush Junior

has had the good grace to admit that a few of his actions were mistaken, but

not Mr. Cheney, who is defiantly unrepentant. The sly smile of his official portraits says

it all: you can have your cake – a huge big cake with oodles of icing – and ravenously

eat it, too.

I can’t hate public figures with whom I

disagree; I can dislike them intensely, but it doesn’t achieve the status of

hate. The one who comes closest to

inciting hate in me isn’t Baby Bush, whose foreign policies I deplored, for on

a personal level he struck me as rather likable. The one whom I can almost hate – almost -- is

Dick Cheney, the former vice-president under Bush. Why him?

Because he’s always managed to have his finger in every pie, public or private, and in the

process reaped a fortune. Bush Junior

has had the good grace to admit that a few of his actions were mistaken, but

not Mr. Cheney, who is defiantly unrepentant. The sly smile of his official portraits says

it all: you can have your cake – a huge big cake with oodles of icing – and ravenously

eat it, too.

And now for a glance at local history to

see who has been motivated by hate, real hate.

Let’s consider some famous New York shootings.

Aaron Burr and Alexander Hamilton

On July 11, 1804, Vice President Aaron

Burr shot former Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton in a duel at

Weehawken, New Jersey. The wounded

Hamilton was taken back to New York, where he died the next day. Some historians assert that Burr fired only

in self-defense, thinking that his opponent meant to kill him, but most are of

the opinion that Burr really meant to kill Hamilton. Who is right, and did Burr truly hate

Hamilton?

|

The duel was the culmination of a long

vendetta between the two. They were on

opposite sides politically, Hamilton being a Federalist and Burr a Democratic

Republican, but much more than that was involved. Hamilton viewed Burr as an unscrupulous opportunist

solely out for no. 1 and tried constantly to thwart him in his career. In the 1800 presidential election, when Burr and

Thomas Jefferson were tied in the Electoral College and the election was thrown

into the House of Representatives, Hamilton did all he could to swing the

election to Jefferson, who in fact did become President, with Burr as

Vice. And Burr did not relish being no.

2.

The last straw for Burr came in 1804, when

he ran as an independent in the New York State governor’s race. Hamilton lobbied his fellow Federalists not to support Burr in his fight

against the Democratic Republican candidate, who overwhelmed Burr in the

election. Learning from a press account

of Hamilton’s denunciation of him at a dinner party, Burr accused Hamilton of

slander and demanded that he apologize or accept his challenge to a duel. Unwilling to apologize, Hamilton felt

compelled by the code of honor to accept the challenge.

Was Burr’s challenge primarily a

political maneuver to redeem his honor and revive his flagging political career,

as some have suggested, or behind it was there hate? Given Burr and Hamilton’s prolonged antipathy,

I come down on the side of hate: Burr meant to kill Hamilton and

succeeded. But at a cost: the duel was

denounced by all and ended Burr's political career. (For a fuller account of the duel, see post

#121, April 6, 2014.)

Edward S. Stokes and James Fisk, Jr.

On January 6, 1872, Edward S. Stokes, a

dapper but impecunious young man about town, shot the controversial impresario

and Wall Street operator Jim Fisk in a midtown hotel. Stokes had stolen away Fisk’s lady friend, Helen

Josephine Mansfield, following which he and Josie had attempted to extract

money from Fisk through a series of lawsuits.

Cross-examination by Fisk’s lawyers on the day of the shooting had

demolished what little reputation Stokes and Josie had left, revealing him as a

scheming fancy man and her as woman of loose morals, in consequence of which

Stokes’s lawyer told him the suit must be dropped. Following this humiliation, Stokes learned

that a grand jury had just indicted him and Josie for attempting to blackmail

Fisk. Frustrated and angry, Stokes

confronted Fisk on the stairway of a Broadway hotel and shot him twice. Fisk was carried to an empty hotel room where

he died the next day, and Stokes was immediately arrested.

|

|

| Worth a shooting? Well, tastes change. Back then "buxom" was in. |

|

| The elegant Mr. Stokes. The girls really went for him. |

Did Stokes hate Jim Fisk? I’m inclined to say no; the shooting was more an impulsive act provoked by his humiliation in court, followed by the news of his indictment. I don’t sense in Stokes the deep, prolonged hate that Burr felt for Hamilton. But if the shooting wasn’t planned in advance, one can ask why Stokes was carrying a revolver. (For a fuller account of the Fisk/Stokes/Mansfield triangle, and what became of Stokes and Josie afterward, see posts #67 and 69, June 28 and July 3, 2013.)

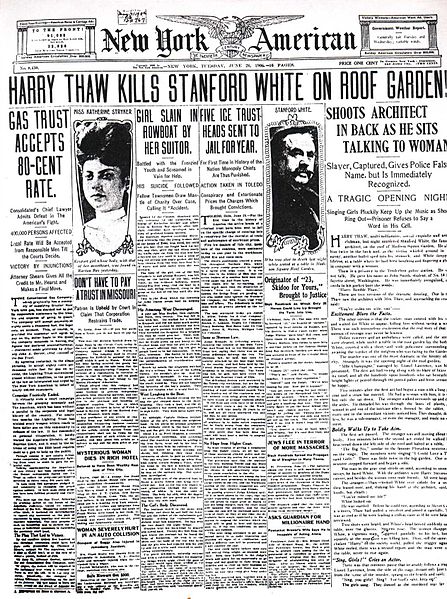

Harry Thaw and Stanford White

On the evening of June 25, 1906, during a

musical comedy performance at the rooftop theater of Madison Square Garden, the

renowned architect Stanford White was shot and killed by Pittsburgh millionaire

Harry Thaw, who was arrested at once.

|

|

| Here she is, on a souvenir card. Hardly an innocent. But you can see what the fuss was all about. |

Meanwhile Harry Thaw had declared his love

for Nesbit, showered her with gifts, and finally got her to marry him. Learning of her prior relationship with

White, he became morbidly jealous, repeatedly pressing her for details about

her affair with White. Intensifying Thaw’s

resentment was his feeling that White had prevented him, an outsider from

Pittsburgh, from being accepted into the city’s elite men’s clubs.

Did Harry Thaw hate Stanford White? I think so, given his ungovernable rage, his

jealousy, his envy of White’s social position and life style, and his obsession

with the details of his wife’s relationship with the older man. Contributing to his mental instability was

his use of cocaine and morphine. (For a fuller account of the

story, and to learn what then became of Nesbit and Thaw – an account that

contains some surprises -- see post

#107, January 5, 2014.)

Valerie Solanas and Andy Warhol

On June 3, 1968, radical feminist Valerie

Solanas shot Pop artist Andy Warhol in his studio at 33 Union Square in

Manhattan. Hospitalized with an almost

fatal wound, Warhol slowly recovered, but his studio, dubbed the Factory, did

not. Fearing another attack by Solanas, from then on Warhol lived in fear and controlled the Factory more tightly, so

that it was never quite again a wide-open meeting place for avant-garde

artists, writers, musicians, and assorted weirdos and crazies. Arrested, Solanas pleaded guilty to reckless

assault and was sentenced to three years in prison.

Everyone then and now has heard of Andy

Warhol, the Prince of Pop, whose works sell for as much as a million, but who

was Valerie Solanas? Born in New Jersey

in 1936, she became estranged from her divorced parents and was abused by her

alcoholic grandfather, to escape whom she ran away and for a while became

homeless. Coming out as a lesbian in the

1950s, when such things were not done, she got a degree in psychology from the University of Maryland, and in

1966 moved to New York City, where she supported herself by begging and

prostitution. Andy Warhol agreed to read

a play of hers with the endearing title “Up Your Ass,” but found it too

pornographic to produce. When he

admitted that he had lost her script, she demanded money in compensation, but

instead accepted bit roles in two of his movies.

In 1967 Solanas self-published the SCUM Manifesto, “SCUM” being an acronym for “Society for Cutting Up Men.” It begins cheerily enough:

“Life"

in this "society" being, at best, an utter bore and no aspect

of

"society" being at all relevant to women, there remains to

civic-minded, responsible, thrill-seeking females only to overthrow the

government, eliminate the money system, institute complete automation and

eliminate the male sex.

The manifesto then asserts that, since

men have ruined the world, women must fix it by creating an organization named

SCUM to overthrow society and eliminate the male sex. To achieve this, violence must be used. “If SCUM ever strikes, it will be in the dark

with a six-inch blade.” Though some have seen

the manifesto as satire, Solanas insisted at the time that she meant every

word of it. But the SCUM organization

had only one member: Solanas.

|

According to producer Margo Feidan, on June 3, 1968, the day of the

shooting, Solanas called on her at home and tried to persuade her to produce

her play. When Feidan refused, Solanas pulled

out a gun and announced, “Yes, you will produce the play because I’ll shoot

Andy Warhol and that will make me famous and the play famous, and then you’ll

produce it.” When Solanas left, Feidan

made frantic phone calls to the police and other authorities, but was told that

you can’t arrest someone for simply uttering a threat. Solanas then went to the Factory, met Warhol,

took out a .32 revolver, and fired three shots at him. The first two missed, but the third pierced

his vital organs. She then also wounded

another man present, and tried to shoot a third, but her gun jammed.

Later that day Solanas surrendered to the police and confessed to the

shooting, claiming that Warhol had “tied me up lock, stock and barrel” and was

going to ruin her. Sent to Bellevue

Hospital for psychiatric observation, she was declared incompetent to stand

trial and confined in a prison for the criminally insane. But in June 1969, being deemed fit now to

stand trial, she pleaded guilty to reckless assault and got three years in

prison. Famous at last, she was

denounced by Norman Mailer, no friend of feminists, as the “Robespierre of

feminism,” but was already hailed by some feminists as a heroine of their

movement.

Released in 1971, Solanas threatened Warhol and others over the

telephone and was arrested again in November and institutionalized several

times. After that she faded from the

scene and reportedly became homeless, while still clinging to her beliefs. In 1988 she died of pneumonia and emphysema

in a welfare hotel in San Francisco at age 52.

Her life inspired a movie and several plays, and her play “Up Your Ass”

was produced as a musical in 2000.

Rejected by mainstream feminists, she was hailed by other feminists as a

“girl Nietzsche,” “Medusa,” and “Medea,” and recognized as the founder of

radical feminism.

In shooting Warhol, was Solanas motivated by hate? Absolutely.

She hated men, and she hated Warhol

in particular, thinking that he meant her ill.

Mentally unstable, she has been described as paranoid or

schizophrenic. Her photographs show a

woman with a look of meanness and hate.

And what did it get her? Fifteen

minutes of fame, then a sad and pointless life; she ended up penniless and

alone. (For more on Warhol, see post

#108, January 12, 2014.)

The Draft Riots of 1863

So far I have cited examples of personal hate, the hate of one

individual for another. Now I shall

present an example of mass hatred, of a whole group of people acting out of

hate. In July 1863 the Irish immigrants

of New York erupted in three days of riot provoked by the draft that the

federal government had just enacted, hoping to bring more recruits to the army

and end the Civil War. Resentful of

authority and wanting no part of the war, the rioters poured out of their

workplaces, marched by the thousand in the streets, and sacked the office where

the draft was being implemented. Far

outnumbering the police (many of whom were also Irish), for three days the

rioters ran wild in the streets, attacking any person or building they thought connected with the draft. Blaming blacks for the draft and the war,

they lynched every black they could lay their hands on, often hanging them and

building a fire under their dangling bodies, around which the women danced

savagely.

|

| A Harper's Weekly print of the time. |

Only when National Guard regiments that had been fighting at the battle

of Gettysburg were rushed back to the city did the rioting stop. The rioters were not drifters and

ne’er-do-wells, but men with steady jobs, and their women. Their savagery – the women even more frenzied

than the men – implies not only a resentment of authority nourished by

centuries of British rule in Ireland, but also a deep-seated racial hatred that

surfaced suddenly when the streets were theirs.

If Irish immigrants were looked down upon by the WASP majority, the blacks were even

lower in the social scale. Many blacks,

having fled, never returned to the city, and the stunned WASP middle class, who

felt threatened even in their elegantly furnished brownstones, harbored more

than ever a profound distrust of what they called the “desperate” or the

“dangerous classes,” most of whom were Irish.

Conclusion

The personal hates chronicled here built slowly over the years,

nourished by an accumulation of apparent grievances, and sometimes by mental

instability. The racial hate behind the

draft riots emerged suddenly, when chaos took the streets, anarchy ruled, and

anything seemed possible; if it built slowly, it was near invisible, hidden in

the depths of a collective psyche. Which

makes me wonder what, if anything, is brewing in my depths, and in the depths of all of us. But maybe it’s better not to know.

The book: The Goodreads giveaway ended on October 12. 509 people entered their name; the winner resides in Illinois. The e-book will soon be available for $3.99.

Coming soon: The Next Big Thing: a Swedish Nightingale, fairies on silver couches in a silver rain, an Electric Torchlight Parade, why Henry Hale Bliss's death is historic, a kewpie doll buried for 5,000 years, the Fab Four, and a dance that collapsed a building.

© 2015 Clifford Browder

The book: The Goodreads giveaway ended on October 12. 509 people entered their name; the winner resides in Illinois. The e-book will soon be available for $3.99.

|

© 2015 Clifford Browder

No comments:

Post a Comment