Long ago, when I was squinting at old New

York newspapers on microfilm, researching the financial antics of Wall Street

speculator Daniel Drew, and the scandalous career of Madame Restell, the

abortionist, I came on full pages of ads that baffled, then intrigued me. The products advertised, both then and

throughout the century, included such items as these:

Swaim’s Panacea

Viner’s Vermifuge

Lydia E. Pinkham’s Herb Medicine

Ayer’s Cathartic Pills

Cocaine Toothache Drops

Hostetter’s Bitters

Wister’s Balsam

Pastor Koenig’s Nerve Tonic

Dr. Williams’ Pink Pills for Pale People

Such were the patent medicines of the

time, which, by the way, were anything but patented. In seventeenth-century England, elixirs that

found favor with royalty received letters patent, allowing them to use the royal

endorsement in marketing; the name “patent medicine” resulted, and stuck.

|

|

| Here they actually say the dread words: venereal disease. |

|

| Yes, there really was such a thing as snake oil. |

And what did these medicines cure? Indeed, what didn’t they purport to cure? Swaim’s Panacea, the product of Swaim’s Laboratory in Philadelphia, was created in 1820 by a Professor William Swaim and claimed to heal scrofula, coxalgia (hip-joint disease), mercurial rheumatism, chronic ulcers, scrofulous ophthalmia, eczema, and poisoning of the blood. Still marketed in the 1890s, it was sometimes pictured as a stalwart Hercules clubbing the multimouthed dragon of disease.

Ayer’s Cathartic Pills, the creation of

Dr. J.C. Ayer of Lowell, Massachusetts, was a “safe, pleasant and reliable

family medicine,” sugar-coated and designed to cure flatulency, dizziness, foul

stomach, rheumatism, liver disorder, kidney complaints, constipation, and

diarrhea. When he retired in 1878, Dr.

Ayer – who was in fact a real doctor – was thought to be the wealthiest

manufacturer of patent medicines in the country.

Cocaine Toothache Drops, manufactured in

Albany, promised an instantaneous cure for toothache and were marketed

especially for children, while also guaranteeing to put the user in a “better”

mood. Hailed as miracle cures, cocaine,

morphine, and even heroin were sold quite legally.

|

| Cocaine for kids, 1885. |

|

| Slaying the dragon of disease. A 1905 ad. |

Hostetter’s Bitters, the creation of Dr.

Jacob Hostetter, a prominent Pennsylvania physician, was promoted by his son

and first appeared on the market in 1853.

Pictured as a mounted hero spearing a writhing dragon of disease, it

claimed to cure colds, dyspepsia, indigestion, constipation, biliousness, and

general debility. When the Civil War

broke out, it was promoted as “a positive protective against the fatal maladies

of the Southern swamps,” and the War Department shipped trainloads of it to the

troops, who surely appreciated it. In

peacetime thousands bought it, convinced that a daily dose would keep them

healthy and in good spirits. Good

spirits certainly resulted, and we shall soon see why.

Dr. Williams’ Pink Pills for Pale People, a

Canadian product manufactured in this country in Schenectady, was sold

throughout the U.S. and the British Empire.

What it offered, besides alliteration, was a cure for St. Vitus’ Dance,

locomotor ataxia, partial paralyxia, seistica (whatever that might be),

neuralgia rheumatism, nervous headache, the after effects of grippe,

palpitation of the heart, pale and sallow complexions, and “all forms of

weakness in male and female.” Whether a

Dr. Williams actually existed, I haven’t been able to determine.

The key to the success of these

mass-produced products was advertising, then in its infancy or at least its

adolescence, and as imaginative as it was energetic, ruthless, and robust. In a previous post, “Advertising: Hucksters

of Yore and Today” (#151, November 1, 2014), I described how patent medicines

were promoted in New York and beyond:

Patent medicine almanacs were

dispensed free on the counters of drugstores and general stores between Christmas

and New Year’s, or were distributed to the public by young boys paid a quarter

a day. And the names of the products appeared in posters on walls and

fences and the decks and cabins of steamboats; on the sides of horsecars; on

signs on wagons roaming the busy streets; on brick piles; on asbestos curtains

in theaters; and on mirrors in public waiting rooms. No flat surface was

safe, and the sidewalks of busy Broadway were enlivened by sandwich men

flaunting the names of remedies fore and aft:

Pocahontas

Bitters

Radical

Cure Trusses

Philipot’s

Infallible Extract

Nor was rural America spared:

the names of nostrums appeared on rocks, trees, fences, barns, and sheds;

adorned the soaring basalt cliffs of the Palisades, visible to passengers on

Hudson River steamboats; and with the completion of the first transcontinental

railroad in 1869, graced telegraph poles and even the Rocky Mountains, and the

Sierra Nevada range in distant California. And as a traveler approached

San Francisco by train, he was informed that “VINEGAR BITTERS

IS ALL THE

GO FOR LOVE!” “Ob-scenery!” protested the New York

Tribune, but to no avail. The ultimate in advertising was achieved

when a nostrum maker bought a steamboat, adorned it with ads for his liniment,

cast it adrift on Lake Erie, and let it float to destruction over Niagara

Falls.

In a nutshell: patented medicines were mass-produced products, allegedly medicinal,

that were marketed aggressively with false statements and extravagant claims.

|

The patent medicine hucksters linked their products sometimes to science or pseudoscience, and sometimes to the Native

American peoples, thought to be in tune with nature and wise in natural

lore. And as if that wasn’t enough, an

ad might show a corpse sitting upright in a coffin, with the words “Killed by

Catarrh!” Or a skeleton of death

escorting a victim toward an open grave past tombstones with skull and

crossbones, until the medicine, pictured as a knight with sword unsheathed or a

hovering angel, effected a last-minute rescue.

And often there was a final enticement: “Recommended by ministers.”

Many patent medicines

were vastly successful, permitting their

What explains the success of

these nostrums, their ingredients undisclosed or misrepresented, and their grandiose

pretensions dubious at best? Throughout

much of the nineteenth century orthodox medicine had little to offer: ether as

an anesthetic, quinine for malaria, a vaccine for smallpox, and not much else

except tender loving care. The limits of

TLC, however conscientiously applied, became evident when pitted against the

ravages of consumption, arthritis, and “delicate” (venereal) diseases. Into this pharmaceutical vacuum the nostrum

manufacturers strode boldly, promising panaceas for every imaginable complaint,

and the public, out of faith and desperation, bought. And if the nostrums’ undisclosed ingredients

included a significant amount of alcohol, cocaine, or heroin, it could only

enhance sales, especially in communities where temperance was enforced by

law. (Not, of course, in New York City,

where a liquor grocery graced every street corner in the slums, and dazzling

mirror-backed bars abounded in more respectable neighborhoods, including the fanciest

hotels.)

Inevitably, in this golden age of pharmaceutical permissiveness, this

Wild West of medicinal outlawry, there were calls for government regulation.

A national food and drug act was first proposed in Congress in 1880, but

it failed to pass. Many publications

relied heavily on patent medicine ads for income, nor were most Americans ready

for reform, believing as they did in certain inalienable rights: the right not

only to worship freely, resist taxation, and damn the government, but also to

self-medicate. On every middle-class

household’s library shelf, along with Tennyson, Longfellow, Little Women, and the Holy Bible, was a

compendium of time-honored home remedies, many of them sanctioned by tradition

and little else:

·

For toothache: 3 drops essential oil of cloves on

cotton, placed in the hollow of the tooth.

·

To prevent or cure baldness: 2 oz. eau de cologne, 2

drams tincture of cantharides, 20 drops each of oil of rosemary, oil of nutmeg,

and oil of nutmeg, to be rubbed on the bald spot every night.

·

For burns and scalds: 4 oz. powdered alum put into a

pint of cold water, then applied to the affected area.

·

For freckles: ½ dram muriate of ammonia, 2 drams lavender

water, ½ pint distilled water, applied with a sponge 2 or 3 times a day.

·

For offensive breath: 6 to 10 drops concentrated

solution of chloride of soda.

·

For deafness: 3 drops sheep’s gall, warmed, put into

ear at bedtime and syringed with warm soap and water in the morning, applied

for 3 successive nights.

Armed with such remedies, why would one need patent medicines, too? Because even the best home remedies didn’t

always work, and how could one resist the glowing promises, the fervent

testimonials, the round, square, drum-shaped, pig- or fish-shaped colored bottles,

or even bottles in the likeness of a lighthouse, an Indian maiden, or a bust of

Washington? Also, many of the nostrums

made you feel so good.

But at the start of the twentieth century things began to change. Muckraker journalists began investigating the

ingredients of patent medicines and exposed their use of narcotics and – worse

in the eyes of some – alcohol.

Hostetter’s Bitters, for example, was 4% herbal oils and extracts, 64%

water, and a whopping 32% alcohol; no wonder it made you feel so good! And the public began to question whether

cocaine belong in toothache drops meant for children, and why users of certain

nostrums developed alarming signs of addiction.

Then, in 1905, Samuel Hopkins Adams wrote a series of eleven articles

for Collier’s Weekly entitled “The

Great American Fraud,” exposing the

patent medicine industry’s false claims and the harm they did to the public’s

health. Turning one of that industry’s

stratagems against it, Collier’s put

on its cover an illustration of a skull with a row of medicine bottles serving

as teeth, and on the skull the words

THE

PATENT MEDICINE

TRUST

PALATABLE POISON

FOR THE POOR

and below the skull, “DEATH’S

LABORATORY.” It’s no coincidence that

one year later, in 1906, Congress passed the Pure Food and Drug Act, the first

of a series of federal consumer protection laws that, slowly but surely,

brought an end to the patent medicine industry.

Morris Fishbein, the longtime editor of the Journal of the American Medical Association, devoted much of his

career to exposing quacks and driving them out of business. But among his targets were osteopathy,

homeopathy, chiropractic, dietary fads, and physical therapy, which should give

one pause for thought.

|

| Add caption |

Not that the quacks – or, if you prefer, patent medicine makers – went

out of business completely. Instead,

they shifted their talents from selling nostrums to promoting deodorants and

toothpastes, using the same techniques they had employed so effectively in

selling nostrums. Never underestimate

the skill and resourcefulness of the American huckster; they’re with us to this

day.

And so are many products once promoted with extravagant or dubious

medicinal claims in the patent medicine era, and now still on the market,

albeit with a change in image and ingredients.

Soft drinks are prominent among them.

·

7 Up, marketed as Bib-Label Lithiated Lemon-Lime Soda

when launched in 1929, contained the mood-stabilizing drug lithium citrate and was advertised as a remedy for

hangovers. The drug was removed from it

in 1948. Now 7 Up is advertised as a

soft drink only.

·

Dr. Pepper, created in Texas in 1880 and marketed

nationally in 1904, was advertised as a

brain tonic and “liquid sunshine,” capable of building up cells broken down by

fatigue.

·

Pepsi-Cola, created in 1893 in North Carolina and

named Pepsi-Cola in 1898, was marketed as a drink that would let you “zoom over

your troubles” and scintillate, and nip an incipient headache in the bud. Whether such claims can be labeled

“medicinal” can be debated, but they certainly came close.

·

Hires Root Beer was created by a Philadelphia

Pharmacist named Charles Elmer Hires in the 1870s and was marketed as purifying

the blood and making rosy cheeks.

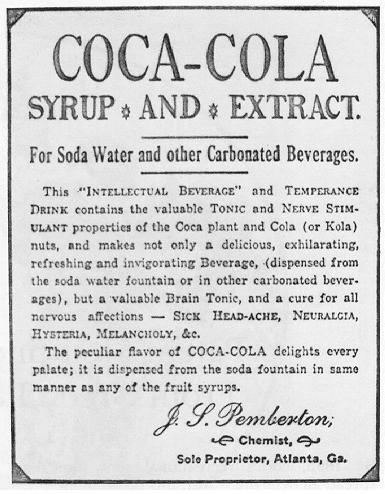

Coca-Cola deserves a mention of its own.

It was invented by Confederate Colonel John Pemberton who, wounded in

the Civil War, became addicted to morphine and sought to find a less dangerous

opiate to relieve his pain. Launched in

Atlanta in 1886, Coca-Cola claimed to cure morphine addiction, dyspepsia,

neurasthenia, headache, and impotence.

The exact formula for Coca-Cola’s natural flavorings has always been a

closely held trade secret, but its two key ingredients originally were cocaine

(hence “Coca”) and caffeine (from Kola nuts).

Cocaine was eliminated in 1903, and in the 1911 lawsuit United States v. Forty Barrels and Twenty Kegs of Coca-Cola the

government tried to make the company eliminate caffeine as well. The 40 barrels and 20 kegs won in court but in

1916 lost on appeal, causing the company to settle the case by agreeing to

reduce the amount of caffeine. Today the

soft drink contains 43 mg of caffeine per 12 fluid

ounces.

Patent medicine makers came to be considered quacks, but what exactly is a quack?

According to my Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary, which is based on

Webster’s Third International, a quack is simply “a pretender to medical

skill.” The word derives from the archaic

Dutch word kwakzalver, or “hawker of

salve.” In olden times kwak meant “shouting”; quacksalvers

touted their wares in a loud voice in the market.

Today “health fraud” and “pseudo-science” are practically synonyms for

“quackery,” which is defined as the practices or pretensions of a quack, but

the matter is by no means simple.

Orthodox medicine has always been suspicious of alternative treatments,

and only with great reluctance came to acknowledge a certain validity in acupuncture

and chiropractic, and this last only after a prolonged legal battle. Because the American Medical Association had

labeled chiropractic “an unscientific cult” and urged physicians not to

associate with its practitioners, five chiropractors sued the AMA for

violations of the Sherman Antitrust Act.

The federal lawsuit Wilt v.

American Medical Association ended in 1987 with a judge’s ruling that the

AMA had indeed violated a section of the Sherman Antitrust Act and engaged in

“a long history of illegal behavior”; while declining to decide whether or not

chiropractic had any validity, the judge issued a permanent injunction against

the AMA to prevent such behavior in the future.

But that was not the end of it. Today

quackbusters, often self-appointed, are rampant. Prominent among them is the organization

Quackwatch, founded in Pennsylvania in 1969 by Stephen Barrett, a now retired

physician, to combat “health-related frauds, myths, fads, fallacies, and

misconduct.” Its targets have included

acupuncture, Ayurvedic medicine, alternative medicine, herbal medicine,

homeopathy, chiropractic, dietary supplements, and organic food – so wide a

range of products and services, including traditional practices going back thousands

of years, as to provoke serious doubts.

Anything alien to modern mainstream medicine seems to merit attack. Despite numerous awards, Quackwatch and its

founder are highly controversial and, in my opinion, deserve just as much

scrutiny as the practices they attack.

My personal take: following my surgery for colon cancer in 1994, I was

told that my cancer had a 40% chance of recurring, but that chemotherapy could

reduce this to 20%. But the idea of

lying there passively at intervals over a period of weeks, while they dripped

an alien substance into me, did not appeal, least of all the added possibility

of unpleasant side effects. As an

alternative, I embraced a nutritional approach and began following an

anticancer vegan diet that included cruciferous vegetables, garlic, soy foods,

and lots of fruits and vegetables generally, preferably organic. This approach involved no nasty side effects

and I am still on it today; the cancer has not returned. So when it comes to a debate regarding the

pros and cons of alternative medicine, I have to come down emphatically on the

side of pro. Friends of mine with cancer

have gone the orthodox way, enduring chemotherapy and radiation and their hideous side

effects; not one of them survived.

I don’t deny that there are cancer

quacks out there, and other quacks as well.

But to pin that label to all forms of alternative medicine is

unwarranted; some of that stuff works.

There are times for mainstream practices, and times for alternatives;

both offer benefits, and both have limitations.

The consumer/patient has to make informed decisions. But watch out where you get your information;

make sure the source is trustworthy, and not simply the self-interested agent

of the medical/ industrial complex (yes, it really does exist) or its

opponents. As always, caveat emptor applies.

|

| Louis Pasteur -- a quack? |

Meanwhile, let’s be glad that the patent medicines of yore have been

buried in the dust of time; there’s little doubt that their promoters – yes,

even the original sponsors of that beloved American icon, Coca-Cola – were

quacks. On the other hand, it’s worth

remembering that Louis Pasteur, the pioneering French microbiologist, and Linus

Pauling, twice a Nobel Prize winner, who advocated massive doses of Vitamin C

for treating various diseases, including cancer and the common cold, were both

denounced as quacks in their lifetime.

As was John Harvey Kellogg, a promoter of vegetarianism and, with his

brother, the creator of Kellogg’s Corn Flakes, a staple of my childhood as

essential to the American scene and psyche as Coke (and I don’t mean cocaine).

|

| Linus Pauling, twice a Nobel Prize winner -- and a quack? |

Coming soon: Where radar,

transistors, sound movies, television, and so much else were pioneered right

here in the West Village, while scandalous things happened nearby.

© Clifford Browder 2015

No comments:

Post a Comment