I’ve become a killer. This will surprise, even shock, my friends,

who think of me as a reasonably calm, peace-loving character, but it’s true. And I kill morning, noon, and night, though

especially at night, when my victims are most plentiful. I kill, and without a qualm, without even a

hint of a flicker of conscience. Not

exactly with joy, but at least with a grim satisfaction. And without mercy.

What

do I kill? Bugs. “What kind of bugs?” you ask. I don’t know, just bugs. Smaller than American cockroaches, some bigger

than ants, some smaller, even minuscule.

Different kinds, though I can’t differentiate them, just call them bugs. But maybe they are German cockroaches (Blatella germanica), smaller than other

species of roaches, though I haven’t heard them speaking German.

|

| German cockroaches. But they're really much smaller than this. Saphan |

|

| This is the way I like to see them. But I don't use K300. Gadi Vishne |

Why do I kill them? Because they’re everywhere, defy gravity by

crawling up walls and on the ceiling of my apartment, won’t let me alone, and

don’t pay rent. In the bathroom in the

morning they’re crawling over my toothbrush or hiding under the soap. In the medicine cabinet I find their egg

cases in the pill boxes and bandage wrappings, and their unholy droppings on everything. As I breakfast in the kitchen, they try to

feast on crumbs from my bread or a stray bit of banana, till I chase them away

and they disappear under the table’s surface, where I can’t pursue them. And as I continue to breakfast, they come

back again, try to sneak another tiny bite.

Finally, as the day wears on, they disappear into their hidden

sanctuaries: any crack or crevice in the walls of my ancient apartment, any bit

of clutter, any remote corner of a shelf, any cluster of bottles, any pile of

newspapers, any heap of plastic bags, and above all the dark infernal recesses

of my ancient stove’s ancient oven.

“Doesn’t an exterminator come once a

month?” you may ask. Of course. His

spraying here and there may result in a few small corpses in a day or two, but

so what? They are legion, and they

proliferate. The exterminator leaves a

stack of glue traps that I dispose of at strategic points in the kitchen, and

within days the traps reap harvests of stuck wigglies waving their antennae

frantically. Their death throes seem to

entice more to join them, till the traps are so full there’s hardly any room

for more. On one 5-by-8-inch trap by the

kitchen garbage can I’ve counted some 400 bugs in all, most of them tiny, some

50 of them bigger. But so what? They persist, they abound. Through sheer numbers, I’m told, the insects

will inherit the earth. If they haven’t

already.

And so, in self-defense, I’ve become a

cunning and ruthless slaughterer, determined that these marauders shall, in

great numbers, die. When at night,

heeding the bladder imperative, I traipse to the bathroom and suddenly turn the

light on, I have my trusty slammer handy – an empty pill bottle with a

flat-topped cap – and bam bam bam I

massacre as many as I can, as they flee in all directions. They have the best chance of escaping if I

catch them on a wall, for my slammer is less effective against a vertical

surface. On the wash basin I usually bam bam bam get several as the others

scurry to safety, but if I find some in the bathtub, they are doomed, for their

dark little bodies stand out sharp against the white enamel, they have a long

distance to go before reaching safety, and I am determined that they shall die

the death. And they do. And if I then go into the kitchen, their

favorite feeding ground at night, and turn the light on, I convulse their

midnight revels in the sink, as bam bam

bam bam bam I wield my kitchen slammer, my Excalibur, and perpetrate a

massacre of dozens, scores. Some escape,

many don’t.

|

| My Excalibur. Minus the vitamin B's, of course. Ragesoss |

Do I enjoy these massacres? Yes and no.

My actions are strictly in self-defense,

so I don’t consider myself a born warrior or sadist; when I mash them, their

death is instantaneous, no writhing, no pain. I don’t feel joy, but I do feel the

aforementioned grim satisfaction, and if they annoy me enough, at least a momentary

flash of anger. And a sense of power,

since I loom large over them like Yahweh smiting the Midianites. And even, if they get on me (as they

occasionally do), a touch of loathing

and hate. But if, as they flee when I

turn the light on, some of them run onto a glue trap cunningly positioned by me

and get stuck there, or if, in the morning, I find a cluster of them – anywhere

from five to twenty -- in an empty yogurt container in the garbage, and I spray

them and kill every last one of the wee beasties, then, I confess, my grim

satisfaction extends to the outskirts of joy.

Mostly, it’s a game, and I’ve gotten

fairly good at it, know where to place the glue traps and where to put my

slammers – one in the bathroom and one in the kitchen – so they’re immediately

available when the light goes on. I

always clear the kitchen table, so as to have a wide and unobstructed killing

field, and if I find the creepy-crawlies in the toilet bowl – and I often do –

I feel a kind of glee when I flush them away to oblivion. And glee again when I find an empty egg case

and some forty tiny creatures stuck fast in a trap. And if I leave a coffee mug half full of

water in the kitchen, in the morning I’m bound to find one, two, three, up to

five winged corpses floating in the water.

(Yes, some have wings, though they never fly.) Do I pity my victims, drowned or mashed? Hardly.

For me, they aren’t capable of true feelings. So what are they? Bundles of instincts, tiny machines. As for Blake’s wonderful line, “For everything

that lives is holy,” I dismiss it as a beautiful lie. Poets are notorious liars.

There was indeed a killer in my family,

but it wasn’t me; it was my father. But

to be fair, I should say a hunter and fisherman, for he loved the outdoors and

loved to hunt and fish. Fishing usually

meant long hours on a quiet lake in northern Illinois or Wisconsin, sitting

quietly in the sun, waiting, waiting, waiting.

Forced to accompany him, I was totally, utterly bored. Did I ever catch anything? Once, as I recall,

some small, flat finned thing that didn’t look like much, but I suppose we had

to cook it and eat it. But when my

father, on his annual fall vacation, went to a lake in northern Wisconsin for

two weeks, he caught plenty and shipped them back in ice.

As for hunting, when I was sixteen he

taught me to shoot a shotgun. I didn’t

like it, for the recoil made my shoulder ache, but I did learn a thing or two

about guns. He took good care of his

guns and used them carefully, always carrying them with the barrel toward the ground,

except when about to shoot. From fall

through spring he took me and my older brother to his gun club, where sportsmen

assembled to sip coffee, swap hunting stories, and shoot trap, aiming at clay

pigeons flung from either of two trap houses.

When they hit a pigeon dead on, it vanished in a puff of dust, and

discreet congratulations were extended.

It was a man’s world, with one exception: the wife of a sportsman who

was just as into shooting as her husband; my father, always quick with

nicknames, called her “Pistol-Packin’ Momma” and, like all the men, accepted

her completely. My mother, if she went

along for the ride, never set foot in the clubhouse, preferring to remain in

the car with a good book.

|

| Not my father, but the exact same look. |

For hunting my father took me into bare autumn

fields, hoping for a shot at a flock of blackbirds or a lone scurrying

rabbit. No blackbirds came our way, and

if a rabbit did finally show up, I never got a shot. Nor did I want to, having no desire to kill

anything. When one of my schoolteachers

lamented the killing of deer – “those beautiful creatures” -- for sport, I

queried my father about it. Far from

dismissing her as a silly old maid who knew nothing about hunting or life, he

explained quietly that hunting is an instinct, stronger in some people than in

others. True enough: strong in my

father, but weak to nonexistent in me.

And so, bugs notwithstanding, I insist that I am not a killer. Left to my own devices, I wouldn’t hurt a

flea. (Unless, of course, it was on me.)

|

| A luna moth. Too eerily beautiful to kill. |

On my many hikes in parks and woodlands, I

never killed an insect, with the exception of a stray mosquito, and then in

self-defense. I loved watching butterflies,

and once stared in awe at the haunting beauty of a luna moth sleeping on a tree

trunk, but I never tried to catch, much less kill, any of them. And if I saw a nectar-seeking honey bee

struggling to free itself from the sticky pollen of the milkweed, I would take

a twig and gently free it so it could fly away.

But there was one exception: if, in the late spring, I saw the white (often

dirty white) tent of the tent caterpillar in the branches of a tree, I would

knock it to the ground with a stick and then trample the teeming, writhing mass

of tiny caterpillars inside it, so they couldn’t defoliate the nearby

trees. Something about that writhing mass

of living things alienated, even disgusted, me – a feeling that I have rarely

felt in nature. Perhaps I should have

let nature take its way, but I love trees and hate to see their leaves consumed

by that horde of tiny mouths.

|

| They make me want to kill. Brocken Inaglory |

|

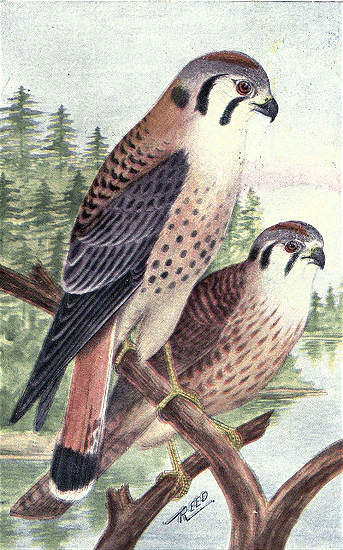

| Sparrow hawks. |

Let

nature take its way: there is mystery in that process, and death. Once, toward dusk on Monhegan Island in

Maine, I was watching a flock of migrating sparrows feeding on birdseed that

Bob and I had scattered on the lawn outside our cabin window, when out of

nowhere a sparrow hawk swooped down to seize one of them as the others

fled. In the dim, fading light I could

barely see the hawk – really a small falcon, the kestrel – spread its tail to

steady itself on the ground, as it consumed its prey. It was unsettling, mysterious, awe-inspiring.

And when I read about how a rattlesnake

sinks its venomous fangs into a startled squirrel, waits patiently as the

squirrel scurries off, each bound pumping the venom deeper till the squirrel

droops, drops, and the snake follows at leisure and slowly consumes its prey

head first, I get that same feeling of horror mixed with mystery and awe. Killing is a part of nature’s way, common and

necessary in the processes of life. But

is it necessary among humans as well?

Here I will bring us back to New York, to

the draft riots of July 1863, during our Civil War, when, even as a great

battle raged at Gettysburg, Irish workers in the city rose up against the newly

initiated draft, destroyed the building where the draft was being processed, looted

and burned every other building they associated with the draft, held off the

outnumbered police, and lynched every black man they could get hold of, blaming

blacks for the draft and the war. Some

of their victims were hanged over a fire, around which the Irish women, by all

accounts more savage than the men, danced in a frenzy. The rioters were not drifters and the

homeless, but men with steady jobs who deserted their workplace and for three

days, joined by their women, raged in the streets. What drove them to this?

|

| No women here, but they were usually present. A Harper's Weekly print. |

That they resented the draft is

understandable. They had come over here

to escape famine in Ireland, and to get free of centuries of English rule. Deep in their psyche was a hatred of

authority, of government, of being forced to do the will of others, and this

hatred transferred to the American government when, desperate to crush the rebellious

South, it initiated the draft. And the

cry “A rich man’s war, a poor man’s fight” had resonance, since the affluent,

by paying $300 for a substitute, could quite legally avoid the draft, whereas

the rioters didn’t have $300. One also has

to suppose a deep-seated racism that suddenly, under these exceptional circumstances,

flared forth. There were a few white

victims too: policemen, soldiers, anyone who interfered with the rioters,

anyone who looked like a “three-hundred-dollar man.” Yet when, after three days of riots, the

military arrived to restore order, the rioters went back to their jobs and

resumed their role of quiet, steady workers.

Is there a killer buried deep in all of

us, or do only a few of us nurse this hidden urge? My pen pal Joe, while doing time in North

Carolina, wrote a series of vignettes about prison life, including an unforgettable

one entitled “Killer Friends.” In the

vignette he explains that, when doing time, you never ask another inmate what

he’s in for; to do so is to court danger.

But sometimes an inmate chooses to tell another inmate, and so it was

that Joe heard the stories of several convicted murderers. One of the stories especially impressed

me.

A young inmate told Joe how, at age

fifteen, he had asked his parents for a motorcycle for Christmas, and they said

they would see what they could do. But

when Christmas came, his parents explained that, regretfully, they hadn’t been

able to afford it. Instantly consumed

with rage, the young man went to his room, got out his shotgun, loaded it, came

back to the living room, and killed both his parents as they were sitting on

the couch. Then, panicking, he grabbed

all the money in the house and rushed to the garage to get into the family car

and flee. And there, in the garage, he

found a shiny new motorcycle; his parents had wanted to surprise him. He is serving two life terms.

What made this young guy tick? I don’t know if he had a history of violence,

but quite possibly he did not. I can

understand his disappointment, maybe even his rage, but I can’t understand a rage

that precipitates murder. Between me and

him a vast chasm opens up.

Another of Joe’s stories is about a man

who killed his wife in a drunken rage, when she announced she was getting a

divorce. He then put her body in his

car, drove to some nearby woods, and buried her there. But two weeks later the state police came

knocking on his door to report that a bear had dug up her body and devoured

some of it; could he explain how she came to be buried there? He then confessed and got a life

sentence.

In these accounts of murder two common

denominators emerge: the murderers had trouble controlling anger and, closely

related, they yielded to impulse. In

both of them there was an appalling lack of judgment, an inability to think of

consequences.

Have I ever experienced violent rage? Just once, years ago, when a waiter in a crowded

West Village gay bar harassed me, telling me not to stand here or there, not to

move around the bar – harassment so intense that I finally just handed him my

half-finished beer and walked out. Why

he chose to bother me I have never fathomed; there was no history of antagonism

between us, and I was behaving no differently from any other patron of the

bar. But I felt intense anger and

stalked the streets for some time nursing it, hoping to meet a friend to whom I

could pour out my story and, in so doing, temper my rage. Alas, no friend showed up, so in the end I just

went home.

This is a trivial story, but it

demonstrates that, when consumed by rage, I never contemplated any act of

violence, wanted only to get rid of my rage.

I could have, at some cost, splashed my beer in the waiter’s face, or

poured it on the floor, or dropped the bottle hoping it would smash, but none

of these acts occurred to me. Deep in me

there was some kind of safety valve, some instinct of self-preservation that

was stronger than any impulse to retaliate.

This safety valve, I assume, is deep in most of us, but absent or

ineffective in a few. We all feel anger

at some point, often justifiably, but we don’t all resort to violence or

kill.

I

have seen the face of rage. Once, long

ago, when I was having lunch in a crowded student restaurant in Lyons, France, we

all suddenly heard a great clatter at another table. Instantly a burly kitchen worker rushed over

to the table where the disturbance was, and found two students in a

confrontation. One yelled feverishly,

“He can’t take a joke!” The other said

nothing, just glared, his features contorted with rage. Fortunately, the burly man calmed things

down, and we all were able to resume our lunch.

But I’ve never forgotten the look of the angry student, his reddened

features warped with rage – rage on the verge of violence. If the burly worker hadn’t intervened, who

knows what might have happened? Rage is

ugly, it distorts. No wonder it’s one of

the seven deadly sins.

|

| The sin of Wrath, as illustrated by Pieter Brueghel the Elder: soldiers massacring or torturing all they encounter. |

Are killers born or made? Is murder deep in our bone and blood, or is

it a product of social forces acting upon us?

Some of us are born hunters like my father, and I would add that there

are born writers, artists, dancers, gamblers, rebels, healers, scholars, and

reformers. From an early age I was

writing – nonsense of course, but writing – so I’m convinced that I was born a

writer, and circumstances then facilitated the urge. So are some of us born killers, or at least born

destined to commit an act of violence?

We don’t want to think so, but at times we’re inclined to assume

it. “Leave it to the experts,” you might

say; leave it to the sociologists, psychologists, criminologists. But at times we uninformed citizens are

forced to have an opinion. When on jury

duty, for instance, and hearing a case involving murder. Or as a voter, when called to vote on issues

relating to the death penalty.

Once, when doing background research for a

novel, I read some books on violent crimes and those who commit them, and was

so shocked by some of the serial murderers described, and their early and total

commitment to killing, that I ruefully concluded that some of us probably are

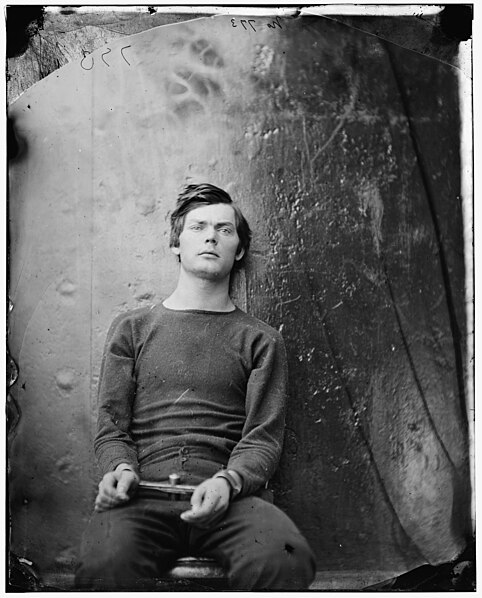

born killers, or at least predestined to violence. And when, on another occasion, I saw Matthew

Brady’s photographs of John Wilkes Booth’s coconspirators, who were tried and

hanged following President Lincoln’s assassination, the photo of one of them,

Lewis Powell, who had attacked but failed to kill Secretary of State William

Seward, struck me; in his hardened features I discerned a killer. Of all Booth’s fellow conspirators, he was

the only one who, following Booth’s instructions, made a serious attempt to

kill a member of the government.

|

| Lewis Powell, after his arrest. Not the Brady photograph, but the same hard look. |

The recurring question of police violence

burst into headlines yet again when, on July 14, 2014 – just one year ago --

the police went to arrest Eric Garner, an unarmed African American selling

cigarettes illegally on Staten Island.

When Garner seemed to resist, officer Daniel Pantaleo wrestled him to

the ground and allegedly put him briefly in a chokehold, a tight grip around

the neck that is banned by the New York police but that was caught on video by

a bystander. Then Garner, lying face

down on the ground, said “I can’t breathe” no less than eleven times. Taken to a hospital, Garner was pronounced

dead an hour later. The medical examiner

ruled his death a homicide, but a grand jury decided not to indict Pantaleo,

setting off protests and rallies nationwide, with passionate utterances of “Black

lives matter!” and “I can’t breathe!”

Some see police violence – especially

against minorities – as the actions of a few bad apples, while others insists

that it results from an endemic police culture that countenances such violence

and is never held accountable. Once

again the question arises: is there an urge to violence, even murder, deep in

all of us that circumstances at times activate?

And is my satisfaction in killing bugs in my apartment -- trivial as it

may seem – a faint echo of that urge?

One common denominator emerges: the victims are the Other, some living

phenomenon from which the assailant or killer feels completely alienated.

The death penalty is an issue where I flip

and I flop. Most of my friends in New

York, good liberals, are against it, don’t even think it bears discussion. But me, I waver. Granted, it’s administered unfairly and can

be opposed on those grounds alone. And

granted, those who are convicted may be innocent, and imprisonment leaves open

the possibility of exoneration later. But

if, as can happen, there is no doubt about guilt, is the frequent alternative

of a lifetime in prison without the possibility of parole – and some or all of

it in solitary – really more merciful? I

wonder. On the other hand, pictures of an execution can chill me to the quick.

|

| The electric chair at Sing Sing, ca. 1900. As so often, whites executing a black. |

From time to time I hear of a crime so

heinous that I’m inclined to justify a penalty of death. When, last May, four Afghan men were

sentenced to death for the mob killing of a woman falsely accused of burning a

Koran, the circumstances of the woman’s death were so horrible that I, like

many, applauded the sentence. The

27-year-old victim, Farkhunda, was thrown from a roof, beaten to death, and run

over by a car, following which the mob set fire to her body and dumped it in a

river. And when, two months later, a

court overturned the death sentence of the four men, I shared in the worldwide

indignation.

|

| This is how the French Revolution did it. |

Truman Capote was criticized by some for

not doing more to prevent the execution of two young men whom he had

interviewed and befriended, and whose story of murdering a family of four in

Kansas he had told with great sensitivity in his work of nonfiction In Cold Blood, published in 1966. There was no doubt about the two men’s guilt,

and they told Capote how, while hitchhiking after the crime, they were picked

up by a lone driver and contemplated killing him and stealing his car. But when the driver also picked up a teen-age

hitchhiker, they abandoned their plan, since now they would have to kill

two. Reading this, I decided they indeed

deserved to die, not just because of the murders they had committed, but

because they had been ready to commit another murder as well.

One argument against the death penalty

that I take seriously is the belief that life is a precious gift that the state

has no right to take. But those who

present this argument are often advocates of free choice, meaning the right of

women to have an abortion, which, no matter how you look at it, is a canceling

of human life. And conversely, many who

support the death penalty are often right-to-lifers, fanatically opposed to

abortion. Granted, the unborn fetus has

committed no crime, whereas those condemned to death presumably have. Still, a life is a life. I find these inconsistencies troubling.

Lacking today in our secular society is a

sense of the sacred, a reverence for the holiness of life. Or if it still exists, it is often embraced

by rigid fundamentalists whose general views many of us find repellent. But perhaps it can be experienced even by

secularists in the form of wonder. Which

at once brings to mind a famous statement by Einstein, who was not

conventionally religious:

The

most beautiful thing we can experience is the mysterious. It is the source of all true art and

science. He to whom the emotion is a

stranger, who can no longer pause to wonder and stand wrapped in awe, is as

good as dead – his eyes are closed. The

insight into the mystery of life, coupled though it be with fear, has also

given rise to religion. To know what is

impenetrable to us really exists, manifesting itself as the highest wisdom and

the most radiant beauty, which our dull faculties can comprehend only in their

most primitive forms – this knowledge, this feeling is at the center of true

religiousness. In this sense, and in

this sense only, I belong in the ranks of devoutly religious men. (Albert Einstein, Living Philosophies, Simon and Schuster, 1931.)

Only those who have

experienced and acknowledged this kind of wonder can reach me with arguments

pro or con on matters of human life like abortion and the death penalty. Only to them will I listen; the others are just

mouthing their biases.

|

| The mysteriousness of nature: a night sky. Jffkrider |

So where do I finally end up? Somewhere betwixt and between, which many

will label as wishy-washy. I’m

occasionally for the death penalty, which can impart a fearful significance,

and almost even a dignity, to death, yet I have grave reservations about it. I’m troubled by abortion, because it involves taking a life, but wouldn’t want it

banned, since that would force women into seeking back-alley abortions, with

all the risks involved. Issues involving

human life are complex and controversial, not easily resolved. Are killers born or made? Perhaps, deep in our psyche, there is a core

of mystery that may never be penetrated.

Why in our ordinary daily lives most of us, whatever the provocation, do

not kill, while a few of us do, seems to defy rational explanation. Theories abound, but aren’t they simply that:

theories? I’m leery of those – and they

are many – who think these matters simple; I cannot. I join Einstein in marveling at the

mysteriousness of life, and in acknowledging that some things are, for us,

impenetrable. We must cope as best we

can, and humbly, with our dull faculties.

Note on Goldman Sachs: Speaking of killing, Goldman Sachs is a whiz

of a bank that in the past has made many a killing in financial markets, as

discussed in post #158, “Goldman Sachs: Vampire Squid or Martyred Innocent?” (December

22, 2014). The squid or innocent (as you

prefer) has just reported disappointing earnings for the second quarter of

2015, raking in a mere $1 billion, as compared with $2 billion a year ago. The big hit on earnings? $1.45 billion that it set aside for

“mortgage-related litigation and regulatory matters.” The bank is in the final stages of reaching a

deal with the Justice Department over its sale of mortgage-backed securities

before the financial convulsion of a few years ago – a matter too complex for

ordinary folk like you (I presume) and me to understand, but one that evidently

involved consummate naughtiness. But

Goldman will survive and flourish; it always has.

Coming soon: The Village Nursing Home: from shopgirls

romping to ragtime, to luxury penthouses with a view of the river. Plus Auntie Mame, and Guinness Stout at age 93. And how did Abingdon Square get its

name? And after that, Patent Medicines,

among them Coca-Cola and 7 Up. (No, I’m

not kidding.)

© 2015 Clifford Browder

No comments:

Post a Comment