As a kid I was fascinated by forbidden

houses. In suburban Evanston, a very

genteel and unthreatening suburban community, there were two kinds: houses

under construction and houses ripe for destruction.

At the end of our one-block street, toward

the end of World War II a victory garden suddenly gave way to workmen gouging

out an excavation, pouring cement for a basement, rearing up skeletons of

walls, installing a second floor and the beginnings of a roof. Which meant that, after a long hiatus brought

on by the Great Depression, residential construction was resuming at last, even

before hostilities had ceased. And next

to the first construction site more workmen started building a second house right

smack next to the first.

On warm summer evenings, long after the

workmen had departed but when light still lingered, and on Sundays when no

workmen appeared, all the kids in the neighborhood, myself included, were drawn

irresistibly to the construction sites and began poking, climbing, crawling

over the half-finished houses. Probably

a warning was posted somewhere forbidding just such intrusions, but none of us

noticed or cared. It was thrilling to

explore the finished first floor, with its vertical beams marking walls-to-be;

to peer down into the dark depths of the basement; and, not without risk, to

climb warily up a ladder to the second floor, with gaping holes below that

might reach all the way to the basement.

It was an adventure to climb up, but coming down was riskier, and you

could see the gaping space below you.

None of us was ever injured, but with hindsight I can see that what we

were doing courted danger. One weekend I

didn’t venture into the houses, but many

others did, and were caught when the police arrived and took down their names,

so they could notify the families. This

intervention put a damper on our adventures, and in time the houses were

completed, sold, and occupied; the new residents had no realization that their

domiciles had once drawn all the kids in the neighborhood like a magnet.

As for the houses ripe for destruction,

they loomed up here and there, the contents emptied: strange hulking

presences that likewise tempted me and some of my friends to explore them. The floors sagged, gaps in the flooring gaped, and everything about the structure suggested a crumbling haunted house. Again with hindsight, I marvel that none of

us ever fell through a hole to the basement or was otherwise injured. I don’t recall any posted warnings; perhaps

it never occurred to anyone that a crumbling structure soon to be demolished

would attract the young and spice their lives with adventure.

|

| Just the kind of house that lured us, though this one is in a rural setting. Nicholas A. Tonelli |

One of these crumbling houses proved

indeed to be haunted. Three of us, now

in our teens, ventured by chance one night into a deserted old house without

even a flashlight to guide us. When we

groped our way into what must have been the living room, in search of what we didn’t

even know, suddenly one of us asked the others, “What is this?” With his foot he was

gently prodding some soft unseen lump on the floor.

Eerily out of the darkness came a man’s

voice: “It’s a human being, son.”

We froze, speechless. Some vagrant – in

middle-class Evanston they were a rarity – had taken refuge there, hoping for a

good night’s sleep, only to have his sanctuary invaded by a trio of teen-age

interlopers. Saying nothing, we tiptoed

away. Minutes later we were out on the

street, and so was he, routed from his sanctuary. He walked slowly on ahead of us, in the very

direction we were going, and out of sheer curiosity we followed him. A block or so later he turned to confront us,

a big stick in his hand.

“Why are you following me?” he asked, a mix

of anger and suspicion in his voice.

“We aren’t!” we protested, mouthing what

was only a half lie, since we were going that way anyhow and had no intention

of harming him.

He eyed us warily a moment, then turn and

continued on his way. This time we

didn’t follow him, intimidated just a bit, and perhaps chagrinned slightly at having robbed him of his refuge and his sleep.

And that was the only haunted

house adventure of my childhood, and a tame enough one at that.

Two other forbidden houses fascinated me

in Evanston. Walking home from grade school, I

often passed a castle-like stone house with a tower that had a narrow stairway winding

upward round its surface. Those stone steps intrigued

me: where did they lead? On them I could imagine Robin Hood and the villainous Sir Guy of Gisbourne engaged in a climactic duel that only one of them could survive. One day, summoning up my courage and hoping

no one was home, I approached the tower and began mounting the narrow

steps. As they curled round the tower, I

discovered that they simply came to an end, the other steps having over time

crumbled away. Quickly I retraced my

steps and left the premises, aware now that the steps led nowhere and maybe

never did. But the castle-like house

still fascinated me.

I never saw the other house but got

reports from my brother, who ranged far and wide on his bike. He told me of a handsome old house near the

lakefront occupied by an aging recluse who lived alone and had no visitors;

receiving all her supplies by delivery, she was never seen outside. Adjoining the house was a garage, and on the

driveway leading to it there was an old car that had been there for decades,

exposed to all the elements and slowly, like the resident, decaying with age

but, unlike her, visible to all.

Of course there was a story. Long ago she and her young husband had

returned from their honeymoon and moved in.

The very first day they were there, he for some reason lingered in the

garage with the car’s motor on, until he was overcome by monoxide and

died. This sudden tragedy plunged the

bride into a state of shock from which she never really recovered. From that day forth she never left the house

and was never again seen by her neighbors.

Removed from the garage, the car still sat on the driveway, a grim

reminder of the tragedy of years before.

In time the car, the house, and the recluse became a legend.

My fascination with forbidden houses did

not end as I reached man’s estate, but it submerged for years, even decades, as

my attention was drawn to a myriad of other preoccupations and adventures. But recently the possibility of a forbidden

house right here in New York City was awakened in me by an article in the New York Times. It told how, four decades ago, a

19-year-old photographer named Bob Troiano was cruising in his Volvo along

Richmond Road in the New Dorp section of Staten Island when he happened to

notice, at no. 2475, behind a rusted iron gate and a centuries-old stone wall,

an old Italianate mansion, its entire façade fronted by a spacious portico, its

roof topped by a cupola. For Mr. Troiana,

it was love at first sight.

“You knew it was a forbidden place,” he

later explained, “but also unforgettable.”

Not until 1990 was he able to buy the

house and pass through the forbidden gate, which by then was rusted shut. The 20-room mansion, he now knew, had been

built in 1855 by a commander of the New York militia who in 1889 sold it to a

German American confectioner named Gustav Mayer. Mayer’s daughters Paula and Emily never

married, for no man was good enough for the father, but the sisters lived on in

the house, painting frescoes of their travels on the walls. In their later years they too became

recluses, confining themselves to their second-floor bedrooms and lowering

baskets from a window to collect groceries, mail, and laundry. Finally, in the 1980s, they and their nurse

moved out.

The house Mr. Troiana had bought was in a

state of advanced decay. It took him a

whole year just to make two rooms on the first floor livable for himself, his

wife, and his daughter. Next, he set to

work on the rest of the house, tearing down unsteady walls, stabilizing those

worth saving, and rebuilding the windows with their original wavy glass. To preserve an authentic atmosphere, he hid

all utilities, all switches, outlets, and ducts. Except for the renovated first floor where he

lived, the house was preserved in a state of controlled decay, with chipped

paint, cracked plaster walls, exposed beams, handsome marble fireplaces, and

ornate molding.

As word of the house got out, Mr. Troiana

was approached by agents wanting to use the house as a setting for fashion

illustrations and articles. Yes, the fashion

industry, though obsessed with the newest and latest, was enamored of an old

house with an eerie atmosphere. Hostile

to the idea at first, in time Mr. Troiana agreed. Since 1992 scores of models have been

photographed there, including one descending a staircase with a madman in

distant pursuit.

Will these fashion shots and the house’s

notoriety persist? Maybe not. Mr. Troiana has put the mansion up for sale

for $2.31 million – admittedly, a rather steep price, though it includes a free

exterior renovation by himself. He is

thinking of relocating to the Southwest, but if he can’t get his price, he’s

quite willing to live on in the house.

Many editors, directors, and photographers hope that he will stay.

What makes a house forbidden? Mystery, crumbling grandeur, a hint of

danger or scandal or the sinister. It

may attract you or repel you, but either way you can’t ignore it.

|

| A skeleton in the Monster Manor, a nonprofit haunted house built each year by volunteers in San Diego and open to the public. |

One variant is the haunted house, which I

became aware of in my childhood through films and radio, this last conveying it

through creaking doors, sinister footsteps, and whispers or screams in the

night. The haunted house probably dates

back to the advent of the Gothic novel in eighteenth-century England, with

melodramatic tales of horror set in half-ruined medieval (or pseudo-medieval)

castles and abbeys – a vogue that persisted well into the nineteenth century

and that even, with variations, survives today.

Nineteenth-century literature made good use of it; think of the role of

the mysterious house (not necessarily Gothic) in Hawthorne’s House of the Seven Gables, Poe’s Fall of the House of Usher, and Charlotte Bronte’s Jane Eyre.

Not to mention the English country houses to which Sherlock and his

sidekick Watson were summoned, when some baffling mystery required a rational

solution. And for a twentieth-century

haunted house one can’t do better than Faulkner’s short story “A Rose for Emily,”

which I strongly recommend to anyone not put off by a touch of the morbid.

For me, conditioned by film and radio, the

classic haunted house is a three- or four-story Victorian mansion with

gingerbread molding, numerous balconies, dormer windows sprouting from steep

roofs, towers and turrets topped by conical roofs, and often a cupola at the

very top. It must have many rooms where

secrets can fester, ghosts stalk. A

prowling malefactor would feel cramped in a bungalow, inhibited in a

duplex.

|

| ProfReader |

|

| A Federal-style house on West 10th Street today. Brownstones had elegance, Federal- style houses had charm. Beyond My Ken |

There was little room for classic Victorian mansions in the congested

city of New York, but its history offers several forbidden or mysterious

residences. In the 1830s and 1840s the

most desirable residential area in the city was Bond Street, which ran the

short distance between Broadway and the Bowery.

Its elegant red-brick Federal-style row houses had marble street-front

trim and sloping roofs with two dormer windows.

Here on this quiet, tree-lined street lived the city’s elite: prosperous

merchants and bankers, former cabinet ministers, an ex-Secretary of the

Treasury, Congressmen, and briefly, Major General Winfield Scott, whom the

Mexican War would soon vault to fame.

But by the 1850s the fashionable residents had decamped, put off by insidious

signs of decay, notably a proliferation of dentists’ offices, and regarding one

of these there hangs quite a tale. For even

in this neighborhood, once the very epitome of taste and propriety, scandal and

violence could erupt.

Residing at no. 31 Bond Street in 1857 was

Dr. Harvey Burdell, a dentist of exceptional skill and the author of several

authoritative works on dentistry. He was also, it would seem, quick-tempered and

quarrelsome, and may have been guilty o/f sexual predation and real estate

fraud. He lived on the floor above the

parlors, with his office in the rear room on that floor. Somehow he had made the acquaintance of Mrs.

Emma Augusta Cunningham, a widow with four children, who then moved into the

building with her family to become his housekeeper … and, it would seem, his

mistress. He leased the house to her and

she ran it as a boarding house – another precipitous downward step for the once

exclusive neighborhood. But Burdell’s

relationship with her was a stormy one.

She wanted him to marry her, but he was not inclined to do so. He accused her of theft of a promissory note,

and she had him arrested for breach of promise of marriage and slander, though

these disputes were settled out of court.

But her lease would expire on the following May 1, at which time he

planned to lease the building to another tenant and so be rid of her.

On the morning of Saturday, January 31,

1857, the young man employed by Burdell to take care of his office discovered,

upon entering, the body of his employer lying dead on the office floor in a

large pool of blood, his features black, his tongue protruding. Physicians and the police were summoned, and

further investigation revealed blood on the floor and walls of the hall

outside, and a bloodstained sheet and nightshirt in a storeroom in the

garret. The doctor who examined the

corpse concluded that Burdell had been strangled by a cord, but also noted

fifteen deep wounds in the body. The

heart was pierced in two places, both lungs penetrated, and the carotid artery

and jugular vein severed. There had

obviously been a struggle, yet no one in the house reported hearing any

screams.

A coroner’s inquest followed and continued

for two weeks amid tremendous excitement. Thousands attended Burdell’s funeral at

fashionable Grace Church, and at the inquest Mrs. Cunningham threw herself on

the casket and exclaimed, “Oh, I wish to God you could speak and tell who done

it!” She then testified that she had

married Burdell secretly in 1856, and as verification produced a marriage

certificate signed by a Dutch Reformed minister who, when called to testify,

recalled the marriage but could identify neither the victim nor the

housekeeper; it now seems likely that the groom was another man impersonating

Burdell. Other witnesses stated that

Burdell had been in fear of assassination, and that Mrs. Cunningham had boasted

that “she had a halter around his neck and he had to do what she wanted him

to.” The coroner’s jury concluded that

Mrs. Cunningham and a boarder named John J. Eckel were principals in the

murder, following which she was indicted for murder. Press and public hailed the finding, but at

her trial in May 1857, thanks to the efforts of her skillful attorney, she was

acquitted for want of solid evidence linking her to the crime. As a result, the case against Eckel, who may

also have been her lover, was dropped.

But that was not the end of it. If Mrs. Cunningham could prove marriage with

the dentist, she would be entitled to a wife’s share of his estate of $100,000,

and if she bore him a child, she would inherit the entire estate. Conveniently, she began to show signs of

pregnancy, and in due time a child was received from Bellevue Hospital with the

aid of an attending physician. But the

physician revealed that he was working with District Attorney A. Oakey Hall,

the dapper future mayor, to exposed this fraud, following which Mrs. Cunningham

was again arrested. Her attorney got the

charges dismissed for lack of evidence, but the Surrogate’s Court ruled that

she and Burdell had not been legally married, so she could not inherit from

him; for a while she left the city. It

also came to light that Mrs. Cunningham’s previous husband, a wealthy

distiller, had been found dead one day in his chair, following which she had

collected his life insurance in the amount of $10,000. But the fact remains that in the Burdell case

the evidence against her was hearsay. As

for Eckel, he seems to have ended his days in prison. In a memoir published in 1897, forty years

after the murder, Mrs. Cunningham’s attorney, Henry Lauren Clinton, reviewed

the case in detail and still maintained her innocence and the validity of her

marriage to Burdell, while deploring the fraud of the bogus baby.

The Burdell murder was never solved. Burdell and Mrs. Cunningham, who died a pauper

in 1887, both lay buried for years in unmarked graves a few hundred yards apart

in Green-wood Cemetery in Brooklyn. In

2007, at the instigation of an amateur historian, both were given handsome

granite headstones.

The headstones can be the final word on

this sensational case. One wonders how

the next tenant of no. 31 Bond Street felt, upon taking possession of the house

on the May 1 following. Could they

ignore the scandal and trial that had so obsessed the city for months, and the

report of floor and walls smeared with blood?

What had been a seemingly respectable Federal-style residence, differing

little from other such structures on the block, might be viewed by some as

cursed, a forbidden house indeed.

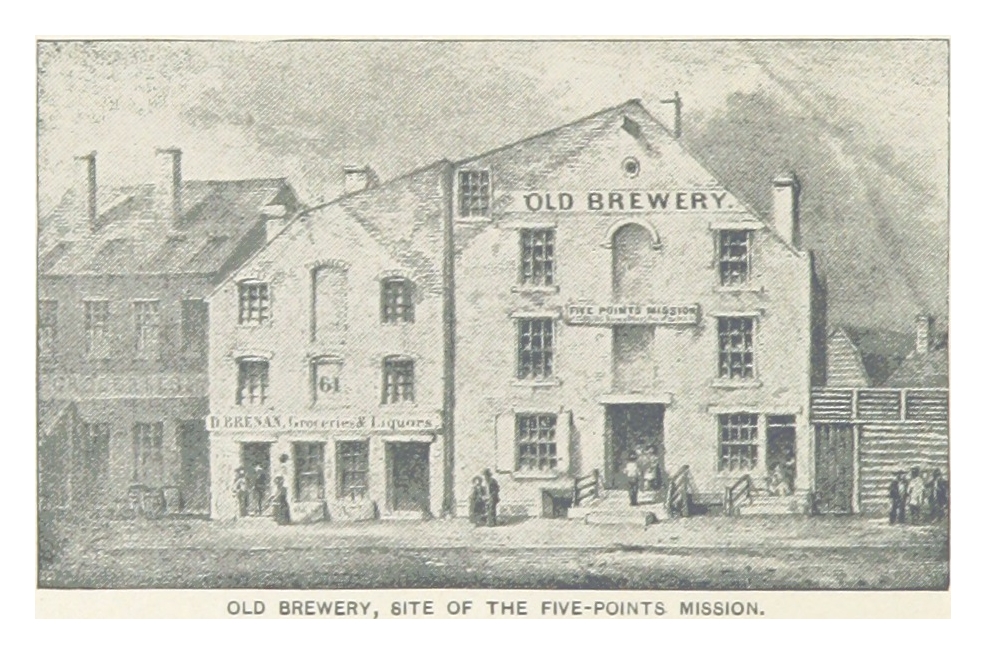

Another nineteenth-century structure

meriting the label of “forbidden house” was the Old Brewery, reputedly the city’s

worst tenement, located near the Five Points, reputedly the city’s worst slum, which

I have already mentioned in post #25 (Sept. 22, 2012). Built in 1792 as a brewery, a new owner –

said to be a respectable church deacon, but certainly an enterprising gentleman

– bought it in 1837 and partitioned it into small apartments so as to get income

from rents. By 1850 the dilapidated

building was notorious, its three hundred residents including thieves who

disappeared into a maze of dark hallways where the police hesitated to follow,

as well as real and fake crippled beggars, drunks, harlots, and the very

poor. A dark, narrow lane running beside

it was known as Murderers’ Alley, in confirmation of rumored murders on the

premises, as well as tunnels and hidden rooms housing buried treasures and

buried bodies.

In 1850 the New York Ladies’ Home

Missionary Society of the Methodist Episcopal Church established a mission school

in the neighborhood and held temperance meetings there as well. In 1851 the Reverend Luckey, formerly the

chaplain to Sing-Sing State Prison, came to the Mission and began visiting the

people in the area, giving counsel and helping them find work. One night in the winter of that year he was

summoned to attend a dying man in the Old Brewery. Though the hour was late, he and one of the

mission converts went, groped their way up creaking stairs, and were led to a

small room near the attic, where a sick man begged Luckey to take him out of

there to a place where Jesus could come.

Luckey got him admitted to the City Hospital, where he married him and

his common-law wife before the man, relieved at being free of the brewery and close to his Maker, died

in peace.

So began the work of the Methodists to

reclaim the Old Brewery and its inhabitants.

In spite of the place’s reputation, the Mission ladies penetrated its

cellars, dark passageways, and attics, conversing with the occupants and

leaving tracts. At first hostile and

suspicious, a man named Brenan who kept a ground-floor grocery and liquor

store next door was won over by the visitors, became a friend to the Mission,

and gave up his liquor business for another job.

|

| Brenan's liquor grocery can be seen on the left. |

In 1852 the Missionary Society bought the

Old Brewery for $16,000. Rumors were

still rife about buried treasures in cellars and passageways, as well as

vestiges of crime. When a man who had

rented a dark, low cellar, ostensibly to store vegetables, gave it up a month

later, saying it was too damp for storage, behind him he left evidence of

recent digging and the removal of a heavy object from the ground by a tackle. Toward Thanksgiving the Society opened the

Old Brewery to the public, who came by hundreds to explore the premises by

candlelight, peering into damp, moldering rooms, now empty, and through

breaches made in the walls to give free passage throughout. So the forbidden building became known to the

public at last. What became of its

former occupants is not recorded. The

purpose of the Methodists was not to preserve the Old Brewery but to tear it

down and replace it with a brand-new Mission building.

Demolition began in December 1852. While it was underway two well-dressed men

appeared who tried to bribe the night watchman to let them enter the building;

the following night they returned, began probing a soft spot in the yard, but

fled upon discovering that the watchman had summoned a policeman. Several nights later the watchman interrupted

five men in the yard who fled, leaving behind some tools for digging. Some time after that the men evidently returned,

escaped detection, and removed some object, leaving behind the hole they had

dug. All of which suggests that the

rumors of buried treasure – or at least of stolen goods – may not have been

pure legend. As for buried bodies, when,

before the demolition, the floorboards of one room were removed, human bones

were found underneath. Replacing the

demolished structure was a new Mission building, a five-story brick building

with rooms at a low rent for deserving families, a schoolroom, and a

chapel. So ended the saga of the city’s

most notorious tenement.

Yet the most forbidden house of that era

was not the Old Brewery, but a palatial brownstone on the Fifth Avenue at 52nd Street, for

this was the residence – and basement office – of Madame Restell, the city’s

most notorious and most successful abortionist.

Needless to say, the Avenue’s fashionable residents were shocked by her

pursuing her occupation in their very midst, and only two blocks from the rising walls of Saint Patrick's Cathedral. That story has been told in part elsewhere (post #86, Sept. 22, 2013),

so I won’t repeat it here, only to say that the neighbors and passersby,

imagining grisly horrors inside, labeled it a House of Death. This scandal ended only with Restell’s arrest

and subsequent suicide in 1878, following which her grandchildren, upon

inheriting the mansion, turned it into the Langham Hotel. One wonders who the guests might have been,

given the building’s history. But the

hotel continued for decades, probably offering a quiet but luxurious alternative to the hurly-burly of

Broadway.

|

| Madame Restell's brownstone mansion at Fifth Avenue and 52nd Street. |

Coming soon: Movie Houses Then and Now: Palace, Sleaze,

and Art. You’ll learn what a strapontin is, how Spanish Gothic could

be combined with Babylonian, why theaters pay a marquee tax, who

patronized the hustlers of 42nd Street, the most crowded

and the emptiest movie theaters I have ever been in, and two haunting movie endings: Greed and Crin Blanc. And after that, terrorism, New York style: Son of Sam.

©

2015 Clifford Browder

No comments:

Post a Comment