Last Monday it began when I checked my

e-mail and found two bits of spam, one urging Viagra on me and the other, Rolex

watches. I clicked them off.

Next, in a doctor’s office, as I was

leafing through one of the stupid magazines always found in doctors’ offices, I

came upon a plea for a topical solution to treat onychomycosis. Onychomycosis? Had I not been a seasoned skeptic, I might

have been gripped with fear. Small print

explained: toenail fungus.

Then, as I glanced at the New York Times (“All the News That’s Fit

to Print”) over lunch, I was assaulted on every other page:

CHANEL

‘Boy Chanel’ bag with stitched chain detail, $6,100

Brequet

Depuis 1775

Reine de Naples Collection

IN

EVERY WOMAN IS

A QUEEN

WHAT

THE WORLD NEEDS

NOW IS

SIMPLE

Push your enterprise

and move the world.

hp

Make it matter.

COPD Kills One Person Every Ten Seconds

Worldwide.

Learn the Complete Cure Now!

Know-hows of Dr. Seo-Hyo-seok, Author of <Free from

Chemical Medicine>, and His Forty One Years of Eradicating COPD!

And all these in that fortress

of sobriety, the Times!

Throughout the day the phone rang with recorded

messages:

· “Hello, this is Bridget. I want to …”

I hung up.

· “Did you know that sixty-five percent of seniors

…” I hung up.

· “Congratulations!

You have been chosen …” I hung

up.

Yes, we are bombarded every day by

hucksters. They try to frighten us,

entice us, inflate our dreams, prod us into action. God knows, there’s enough to frighten us:

· baldness

· erectile dysfunction

· depression

· the end of democracy as we know it

· constipation

· bad breath

· global warming

· 5 o’clock shadow

· B.O.

But they also promise us

· wealth

· health

· glamor

· sex appeal

· security

· success

And let’s face it, we

wouldn’t mind having all of them, and more.

| Millais, Bubbles, 1886. |

As I know from a trip long ago to Europe,

foreigners blame us for these assaults.

True enough, in many ways, but modern advertising is not the invention

of American advertisers. The man hailed

as “the father of modern advertising” was in fact an Englishman, Thomas J.

Barratt (1841-1914), who as chairman of the soap manufacturer A&F Pears

pioneered what is now known as brand marketing.

“Good morning. Have you used

Pears’ soap?” was his slogan, a catch phrase that was famous well into the

twentieth century. He got a testimonial

praising Pears soap from actress Lillie Langtry, a reigning beauty known for

her matchless complexion, which was the first celebrity testimonial in

advertising history. Ruthlessly

inventive, he turned John Everett Millais’ painting Bubbles, showing an adorable little boy with golden curls blowing a

bubble, into an advertisement by adding a bar of Pears’ soap in the

foreground. Millais is said to have

protested this, but Barratt had bought the painting and therefore owned the

copyright. This was not the last use by

far of the image of an adorable child to market products successfully;

nineteenth-century advertising was big on childhood innocence, the more

sweet-faced the better.

|

| On the radio you heard bellhop Johnny's resonant call, "Call for Phillip Morris!" Alexisrael |

FRAGRANT

SOZODONT,

FOR

Cleansing, Beautifying and Preserving

THE TEETH

From youth to old age.

SOLD EVERYWHERE.

But this was nothing, compared to posters

and certain pages in the newspapers throughout the century featuring such

products as

Swaim’s

Panacea

Wm

Radam’s Microbe Killer

Holloway’s

Pills and Ointment

Viner’s

Vermifuge

Dr.

Girard’s Ginger Brandy

Dalley’s

Magical Pain Extractor

Dr.

Lin’s Celestial Balm of China

Pastor

Koenig’s Nerve Tonic

Pink

Pills for Pale People

The secret of the success of

some of these nostrums is revealed in the formula of Hofstetter’s Bitters,

advertised as a cure for many ills: 4% herbal oils and extracts, 64% water, 32%

alcohol. That 32% was much in demand in

communities that had embraced temperance by law.

In an age when mainstream medicine had but

few sound remedies – quinine for malaria, a vaccine for smallpox, and little

else – the nostrums of the patent medicine men had wide appeal, all the more so

in the absence of government regulations.

Whatever ills the public suffered from, “certain

delicate diseases” (V.D.) and “self-abuse” included, the advertisers promised

marvelous results. The nostrums were

sold in every conceivable kind of bottle: square, round, drum-shaped,

pig-shaped, fish-shaped, in the likeness of an Indian maiden or even the bust

of Washington. Manufacturers hoped they

would end up as adornments (and perennial ads) on parlor mantels and whatnots,

but many were smashed to pieces by imbibers fearful lest their secret tippling

be discovered.

|

| Patent medicines on a shelf in a general store today. Wolfgang Sauber |

(Why the name “patent medicines,” by the

way, when they were definitely not patented?

Because, in seventeenth-century England, elixirs that found royal favor

received letters patent letting them use the royal endorsement in

marketing. Nostrum makers generally

avoided patenting their products, because to do so would have meant revealing

their ingredients; they no more wanted

to do that than Coca-Cola and Pepsi do today.)

| Here the near forbidden words "venereal diseases" are actually stated. |

Patent medicine almanacs were dispensed

free on the counters of drugstores and general stores between Christmas and New

Year’s, or were distributed to the public by young boys paid a quarter a

day. And the names of the products

appeared in posters on walls and fences and the decks and cabins of steamboats;

on the sides of horsecars; on signs on wagons roaming the busy streets; on

brick piles; on asbestos curtains in theaters; and on mirrors in public waiting

rooms. No flat surface was safe, and the

sidewalks of busy Broadway were enlivened by sandwich men flaunting the names

of remedies fore and aft:

Pocahontas Bitters

Radical Cure Trusses

Philipot’s Infallible Extract

| Yes, back then snake oil really did exist. |

Nor was rural America spared: the names of

nostrums appeared on rocks, trees, fences, barns, and sheds; adorned the

soaring basalt cliffs of the Palisades, visible to passengers on Hudson River steamboats;

and with the completion of the first transcontinental railroad in 1869, graced

telegraph poles and even the soaring Rocky Mountains, and the Sierra Nevada

range in distant California. And as a

traveler approached San Francisco by train, he was informed that “VINEGAR BITTERS

IS ALL THE

GO FOR LOVE!”

“Ob-scenery!” protested the New

York Tribune, but to no avail. The

ultimate in advertising was achieved when a nostrum maker bought a steamboat,

adorned it with ads for his liniment, cast it adrift on Lake Erie and let it

float to destruction over Niagara Falls.

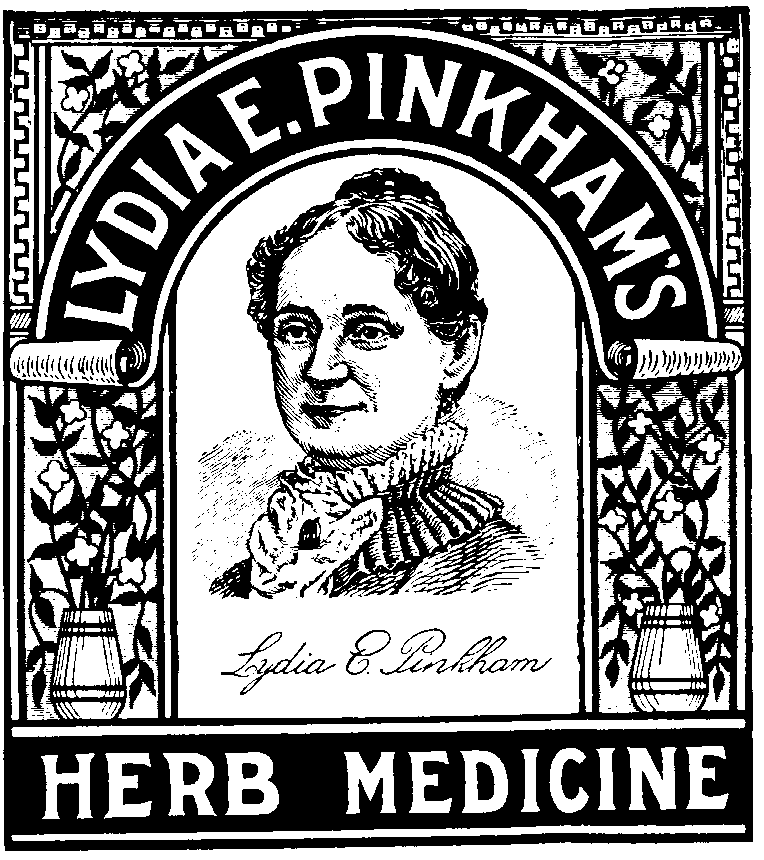

Most of the patent medicine men were

indeed men, but one notable exception was Lydia Pinkham, a Massachusetts

housewife who, like many women of the day, brewed a home remedy for “female

complaints” and gave it away free to her neighbors. In 1875, with the family’s fortunes at low

ebb, one of her grown sons suggested making a business of the family

remedy. Composed of five herbs and some

alcohol, it was immediately successful, and production was transferred from Lydia’s

stove at home to a factory. Her skill in

marketing to women made Lydia E. Pinkham’s Vegetable Compound, with her features

on the label, one of the most popular nostrums of the time, a modified version

of which is still available today. Eager

for relief from menstrual and menopausal symptoms, vast numbers of women wrote

to her, and she dutifully answered them, even after her death, since her staff

filled in for her, until a photo of her tombstone in the Ladies’ Home Journal in 1905 exposed the ruse. The Pinkham company then explained – somewhat

lamely – that they never meant to suggest that Lydia herself was answering the

letters, which were being answered by her daughter. Today Lydia is hailed by feminists as an

early crusader for women’s health at a time when women’s health issues were ill

served by the male-dominated medical establishment. Her descendants operate a clinic bearing her

name in Salem, Massachusetts, to offer health services to young mothers and

their children.

|

| Circa 1875, but still on the market today. And back then she didn't have to look glamorous. |

Muckraker journalists’ exposés of the

patent medicine industry led to the first Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906, which

required that ingredients be labeled, and a revised statute of 1936 that banned

alcohol, narcotics, and stimulants altogether, following which the patent

medicine makers shifted their attention to marketing deodorants, toothpastes,

and shampoos. Today herbal concoctions

promoted as nutritional supplements raise similar issues as the earlier

nostrums once did regarding exaggerated claims, even though today’s claims are

carefully phrased to avoid attracting the attention of regulators.

Clearly, the full-page

ad in the Times promoting a complete

cure for COPD, cited earlier, is right in the tradition of nineteenth-century

patent medicines. The techniques of the

nostrum makers are with us to this day.

And what, by the way, is this mysterious COPD that poses such a threat

to our health? Chronic obstructive

pulmonary disease, which, according to Dr. Seo Hyo-seok’s ad, is the fourth

leading cause of death in the world, predicted to become the third in

2030. A quick bit of online research

confirms the existence of COPD, which includes both chronic bronchitis and

emphysema. Further research confirms that Dr. Seo Hyo-seok is a Korean doctor who, using only Korean medicine,

claims to have cured thousands of patients.

Whatever their style of advertising, I don’t dismiss unorthodox medical

approaches out of hand, and the conditions he is treating are for real, and

life-threatening as well. So if you have lungs,

watch out!

Coming soon: Advertising: Ads Ridiculous, Annoying, Despicable, and Fun.

©

2014 Clifford Browder

This comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

ReplyDelete