Gentrification is a term that raises

hackles. Usually it means trading one

thing for another: gutsy for genteel, old neighborhoods with human-scale

buildings for luxury high-rises; low rents for high rents; working class and

bohemia for solid white-collar middle class; mom-and-pop stores for boutiques;

charm for soulless modernity. But things

aren’t always that simple. How about

Greenwich Village, especially the West Village, where I have lived since the

early 1960s? What has happened to

it?

I have just finished John Strausbaugh’s

epic 624-page chronicle The Village: 400

Years of Beats and Bohemians, Radicals and Rogues: A History of Greenwich

Village, which I highly recommend to anyone interested in the subject. It ends with an Epilogue where survivors of

another time lament the recent gentrification of the Village and the loss of a

wild, radical, anything-goes spirit, funky and creative, that pervaded it back

in its low-rent days. Yes, that spirit

is gone, along with the low rents that once attracted young writers, artists,

and enterprising theater people who made, or tried to make, wild things

happen. But even they represented a kind

of gentrification, for the Village, as Strausbaugh demonstrates, has

undergone a series of gentrifications.

When I came to the Village in the 1960s,

another young writer I got to know, very WASP, told me how his Italian landlady

was learning that she could rent safely to newly arrived non-Italians, who

could be counted on to pay their rent.

So the arrival of people like him and me – the very ones who diluted the

working-class Italian population that Tammany boss Carmine DeSapio had counted

on at election time (see post #135) – constituted a wave of gentrification,

even though the streets and buildings of the Village didn’t change. And I recall a vignette in the neighborhood

weekly The Villager, which was

delivered free to everyone’s doorstep, briefly describing two girls, barefoot,

eating ice cream cones, and observing, “Isn’t that what the Village is all

about? Two barefoot girls eating ice

cream cones.” Which said nothing about

the influx of gay people, Off Off Broadway, the jazz scene, and the prevalence

of drugs and booze. The Villager, of course, was where you went for news of the PTA and

what the Girl Scouts were up to, and not much else. So back then, obviously, there were many

Villages, perhaps as many as there were Villagers.

In the early 1900s political radicals and

free lovers flocked to the low-rent Village.

The Irish and Italian working-class residents, who considered the

Village theirs, looked askance at men with long hair and even more at women

with short hair who drank and smoked openly in the company of these outlandish

males. (Generation after generation, the

Village has always lured a fresh version of the New Woman, to the fascination

of the press and public.) Wild politics

and wild art followed. But by the early

1920s the radicals were lamenting the passing of the Golden Years, as bars and

restaurants and boutiques opened to accommodate the weekend tourists who

flocked to the Village via the recently extended IRT subway line, eager to see

the Village’s weird bohemian denizens and be shocked and fascinated by its New

Women, who necked freely at parties and wore bobbed hair. Locals complained that this wasn’t the

Village they grew up in, and some artists moved out, unable to afford the

rising rents. (Sound familiar?)

Prohibition brought speakeasies, and the

Depression brought real and imitation proletarians and Communists, among the

latter none other than a Harvard dropout named Pete Seeger, whose radicalism

took the form of music. And the WPA kept

many a Village artist and writer from foundering in poverty. No, this wasn’t the Village of the Roaring

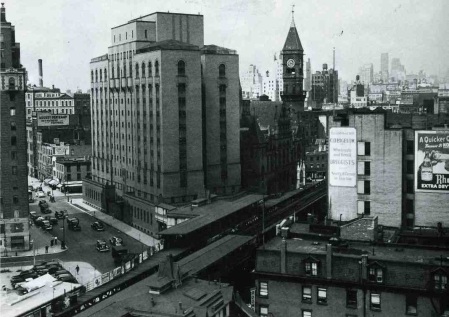

Twenties, least of all after the Mafia moved in. But it was still different: 14th Street was

the dividing line between uptown and downtown.

Uptown meant money, power, elegance, and class; downtown meant hip,

artsy, scruffy, and wild. For all its

changes, the Village was still the Village.

Which brings us to my time in New

York. In the 1950s I was far uptown at

Columbia University, but weekends meant subway trips to the Village and its gay

bars, trips that left studies and a pretense of heterosexuality behind, and

generated a kind of freedom, partial and temporary, but freedom even so. And friends of mine began moving down to the

Village, which planted in my mind the notion of doing the same. And in 1959, I did, giving up a spacious

two-room apartment near the campus for a crummy one-room apartment on West 14th

Street with a teetering table, one dingy window with a view of nothing, and a

ravaged ceiling with a bare light bulb and peeling paint.

But oh how that ceiling astonished me,

becoming a cratered lunar landscape, then pocked skin whose blemishes were

entrancingly beautiful, when I stared at it high on peyote! And how that bare light bulb overhead

obsessed me, becoming the life-giving sun to whom I of all mortals was chosen to

offer my seed in a consummation on which the fertility of the whole world

depended. (A consummation that I had to

fake, since being high gives visions but leaves your dingus limp; I did my

best, not wanting to let the universe down.

For the whole crazy story, see post #62, Abnormal and Paranormal

Adventures.)

So there I was, indulging in my one and

only experiment with drugs, and in less exalted moments sticking my

middle-class nose into the Gaslight Café on MacDougal Street, to hear

second-rate Beatniks spout their sometimes amusing but never brilliant stabs at

poetry. All this because I had read

Allen Ginsberg’s Howl and been

transported by it. (I still am.) Yes indeed, a weekend tourist (I had a

weekday job) having a go at playing bohemian, unaware that in so doing I was

participating in an old Village tradition that went back decades at least. And this in the Village of barefoot girls

gobbling ice cream cones!

In 1961 I returned from a year and a half

in San Francisco and got an apartment on Jane Street, then in 1968 quit my

teaching job and met my partner, Bob, also a Village resident. And in June 1970 we moved into the

rent-stabilized apartment on West 11th Street where we still reside

(once in a rent-stabilized apartment, one moves out only feet first). Which brings us to the threshold of the

Golden Years (the Village has had many Golden Years) that the survivors in

Strausbaugh’s Epilogue remember with nostalgia.

Yes, something of that time has been lost

today, but let’s see what else gentrification has wrought besides high

rents. The heart of the Village hasn’t

changed outwardly, being an officially recognized Historical District, though

the commercial fringes are fair game for developers, with resulting ugly glass

boxes looming here and there, though distant enough to leave the human-scale

old buildings and quiet side streets intact.

So what has changed and what do I regret?

How about the Women’s House of Detention,

that depressing twelve-story monolith of a prison looming smack against my

local library where Sixth Avenue and Greenwich Avenue converge? Do I miss it, half Bastille and half Bedlam,

and the stories it inspired of cockroach-ridden cells, wormy food, and abuse of

inmates by other inmates and staff? Do I

miss the volleys of obscenity issuing from it in the evening when inmates

called down greetings to their friends, lovers, and pimps on the sidewalk, who

shrieked answers laced with obscenities?

No, not much. Least of all when

the monstrous thing was torn down and replaced with a charming little park

where I have often strolled. Score 1 for

gentrification.

| The Jefferson Market Garden |

|

| The Hudson River Park, looking south from Christopher Street to Pier 40. I often walk here. |

By

the 1970s the Village had become a sexual playground, and gay men, far from

hiding their sexuality, flaunted it. I

recall the meatpacking district in the northwest corner of the Village near the

Hudson when it was a sparsely populated commercial area with shabby streets given

over to wholesale meatpacking; passing by, I often saw butchers and meat cutters

in blood-stained aprons, graffiti-ridden walls, and rows of carcasses dangling

from hooks outside the meatpacking establishments. But by the 1970s the neighborhood had become wild with gay sex clubs and leather

bars with enticing names like the Mineshaft, the Anvil, the Ramrod, the Cock

Pit, and (I’m not inventing this) the Toilet.

At the Anvil at 14th Street and Tenth Avenue drag queens

performed on a runway, and naked go-go boys pranced up and down the bars and

did amazing gymnastics, and patrons resorted to the dim basement for sex. The Mineshaft at Washington and Little West

12th Street was even wilder: in a dim back room men had sex in

cubicles, others submitted to anal fisting, and still others knelt in a bathtub

for the fun of being urinated on. And to enjoy these delights, one had to adhere to a strict dress code: no colognes or perfumes; no suits or ties; no designer sweaters; no disco drag or dresses. Preferred dress included leather and Western gear, Levis, jocks, action ready wear, and uniforms. As for action, according to witnesses the nearby Toilet was even worse.

|

| Gansevoort Street in the Meatpacking District, 2007. Still shabby in places. Juliana Ng |

This scene passed me by, for I wasn’t into

leather or anonymous sex; being in a relationship, I didn’t need the joys of

the Mineshaft or the Toilet. The most

that Bob and I did was dance at the Goldbug, a Mafia-run disco with the

traditional thug at the door, a male go-go dancer, and ear-splitting music –

wild for us, but tame by the standards of the day. And when I read a letter in the press by a

Village resident telling how, when she and her family walked the Village

streets, “liberated” gay men eyed her twelve-year-old son brazenly, I shared

her indignation and yearned for the good old days of clandestine gay life, when

heterosexuals weren’t intentionally molested.

If this was gay liberation, I wanted no part of it.

In the 1980s the wild phase of gay liberation came to an end because of AIDS, which the Christian right hailed as God’s punishment on these sinful degenerates. A young man dying miserably of AIDS was a standard scene, along with Satanic rituals, bloody abortions, and teen-age murders, in the lurid Hell Houses sponsored by various churches in an effort to dramatize the wages of sin. But I saw, and still see, the AIDS epidemic as nature's way of rebalancing, its mysterious and often cruel way of curbing excesses.

| A new kind of spook house, thanks to the Christian fundamentalists. |

In the 1980s the wild phase of gay liberation came to an end because of AIDS, which the Christian right hailed as God’s punishment on these sinful degenerates. A young man dying miserably of AIDS was a standard scene, along with Satanic rituals, bloody abortions, and teen-age murders, in the lurid Hell Houses sponsored by various churches in an effort to dramatize the wages of sin. But I saw, and still see, the AIDS epidemic as nature's way of rebalancing, its mysterious and often cruel way of curbing excesses.

|

| Closed until further notice. |

Today the meatpacking district is full of

pricey restaurants and boutiques, gourmet food retailers, and nightclubs where

on weekends trendy people sip overpriced drinks three-deep at the bar. The district is even promoted as “glamorous” and a “must-see,” and there are

walking tours for the uninitiated.

The Gansevoort Meatpacking NYC, a new luxury hotel at 18 Ninth Avenue, offers breathtaking panoramic views of the city and sunsets over the Hudson, and a rooftop swimming pool with underwater lights. And at Ninth Avenue and West 14th Street there is even a glass-walled Apple store where I have gone several times to have my computer looked at by a “genius.” The Toilet, I’m informed, is now a fancy restaurant, a transformation that I can’t regret. Score 3 – or maybe 3, 4, 5 – for gentrification. No need to keep score any more; my point is made.

|

| The Meatpacking District today: a girl go-go dancer dances on the bar at the Hogs n' Heifers. A scene for the well-scrubbed and young. David Shankbone. |

The Gansevoort Meatpacking NYC, a new luxury hotel at 18 Ninth Avenue, offers breathtaking panoramic views of the city and sunsets over the Hudson, and a rooftop swimming pool with underwater lights. And at Ninth Avenue and West 14th Street there is even a glass-walled Apple store where I have gone several times to have my computer looked at by a “genius.” The Toilet, I’m informed, is now a fancy restaurant, a transformation that I can’t regret. Score 3 – or maybe 3, 4, 5 – for gentrification. No need to keep score any more; my point is made.

|

| My Apple store at Ninth Avenue and West 14th Street. No go-go dancers, just geniuses. AchimH |

Of course the Village in those days was

more than screaming women at the House of Detention and gay men having

anonymous sex indoors and out. There was

jazz, theater, and cabaret, all of them with a wild side at times. The

funky creativity of the time seemed to involve self-destruction as well, and

drugs and alcohol took their toll. But

as the rents went up, the really wild side – Beats and hippies, artists and

musicians -- moved to the East Village, leaving what became known as the West

Village relatively quiet. I remember crossing

Third Avenue into the East Village and sensing at once a different, shabbier, wilder

atmosphere. Above all on Saint Mark’s

Place there were head shops, often incense-ridden, stepping into which was like

embarking on a drug-induced adventure.

They offered everything but drugs themselves (though drugs were probably

available close by): drug paraphernalia of every kind including pipes and water

pipes, psychedelic posters with glaring colors and ornate lettering, and dim,

weird lighting that reminded me of my peyote fantasies. I didn’t mind savoring this atmosphere

briefly, but it always kindled in me a

keen longing for the outdoors and normal air and light.

|

| Saint Mark's place today: less shabby, less psychedelic, less wild. Beyond My Ken |

Today the 14th Street boundary

between uptown and downtown seems to have vanished, and Village rents are often

higher than on the Upper East Side. Bleecker

Street near where I live is lined with designer clothing stores – Marc Jacobs,

Brunello Cucinelli, Ralph Lauren – that I never enter, and right downstairs is

the Magnolia Bakery of Sex and the City fame,

sought out by busloads of tourists, and foreign visitors with guidebooks, who

click photos of one another in front of the fabled bakery and sit on my

doorstep gobbling delicious cupcakes that I, a good vegan, shun.

|

Even in winter they line up. I'm four flights above.

joe goldberg

|

Do I hate the tourists and the cupcake

gobblers and the patrons of the pricey stores?

No, not at all. They don’t

threaten me or anyone else, and if sometimes they leave a little litter –

mostly crumb-filled cupcake wrappings and crumpled paper napkins – at least it

isn’t used condoms or drug stuff. And

they show that today’s Village, however gentrified, still has vitality, albeit

a vitality different from that of the Golden Age of yore, whichever Golden Age

one has in mind. And not all the

restaurants are overpriced; when I go out with friends for lunch, within

walking distance we can eat Irish, Indian, Chinese, or Mexican and stay within

our budget. Nor is this a gated

WASP-only community; running errands I may hear four or five foreign languages

and see a sari, or even a burka veiling a Moslem woman from head to foot with

only two thin slits for her eyes.

Someday a new batch of survivors will look

back to a Golden Age when foreigners with their noses deep in guidebooks

flocked to the Village, and people lined up in front of the storied Magnolia

Bakery, mouth watering at the mere thought of the scrumptious little cupcakes

within, and cyclists zoomed for miles along a riverside bike path with great

views of the Hudson, and sunbathers baked their skin stretched out on the real

or fake grass of a pier jutting out into the river. Ah, those were the days!

A note on the East Village: The New

York Times of April 6 last announced that outlaw artist Clayton Patterson

was finally leaving the Lower East Side where he has lived for 35 years, most

of it in a storefront home at 161 Essex Street.

A photo shows him as a stocky man with unkempt long gray hair topped by

a baseball cap embroidered with a grinning skull, his beard in a double braid

tumbling down his chest: the very image of the rebel artist, backed up by a

phalanx of admiring musicians, sinister-looking types in leg-clinging jeans and

dark jackets, all staring at the camera defiantly. And why is he leaving? Because the wildly

creative East Village he knew and loved is being invaded by luxury apartments,

corporate chain stores, overpriced parking meters, and pretentious restaurants

– in short, gentrification.

“There’s nothing left for me here,” he

told the Times reporter. “The energy is gone. My community is gone. I’m getting out. But the sad fact is: I didn’t really leave

the Lower East Side. It left me.”

The moment the Canadian-born artist

arrived in New York in 1979, his world had been the Lower East Side’s

squatters, anarchists, tattoo artists, drug-ridden poets, and skinheads, the

outcasts and the down-and-outers he photographed repeatedly, and whose

brutal ousting from Tompkins Square Park by the police in 1988 he recorded on

tape. One crucial event determining his

departure was the eviction at age 88 of artist and actor Taylor Mead from his

apartment on Ludlow Street (see post #91), following which Mead died within a

month. “No one gave a damn about Taylor

Mead,” he declared, and admitted that he feared the same fate here for

himself.

|

| Graffiti on an East Village telephone box advertising a 2012 reunion of survivors of the 1988 Tompkins Square Park riot. David Shankbone |

So where is this last of the bohemians

going? To a chalet in the Austrian

village of Bad Ischl, in the Alps. Why

there, of all places? Because a creative

community of writers, artists, tattoo designers, and musicians is flourishing there,

and because he is “big” as an underground photographer in Austria, far more so

than back here. His friends see in his

departure further evidence of the cultural decline of New York, which they

insist is becoming a playground for money and sterilized housing. Yes, even the outlaw East Village is

succumbing, and maybe the loss there far outweighs the gain.

Coming soon: In two parts: Norman Mailer, acclaimed author, womanizer,

wife-stabber, drunk. His brilliant coverage of the 1967 Pentagon March and the chaotic 1968 Democratic convention in Chicago, including a police riot and plenty of tear gas and Mace.

©

2014 Clifford Browder

It was a beautiful quiet evening during the Christmas holidays—quiet, because a thick carpet of snow had all but halted traffic.

ReplyDeleteA small group of carolers stood in the corner of Sixth and Greenwich, their wool-wrapped faces turned up, towards the top of the Women's House of Detention. As they sang of angels on high, the scene conjured up a perfect vintage Christmas card image, something one might have found on the cover of The New Yorker or in the public square of small town USA.

A few friends and I were heading for a party, but we had to pause and take in this serene, seemingly out of place holiday tableau.

We hadn't stood there long before a rough, butch tar-and-nicotine New York voice came down from a top floor window and blasted us all back to reality.

"Get the f--k outta here!"

A wonderful Village anecdote, and another point for gentrification. Many thanks.

Delete