This is the fourth and last post about exiles in New York. It deals with some who came here as a result

of Hitler’s rise to power in Germany and the Fall of France.

Strife among the Gauls in exile

In the lobby of a New York hotel, during

World War II, the well-known French playwright Henri Bernstein, upon

encountering fellow French exile André Maurois, slapped him twice -- once, he

said, as a Frenchman, and once as a Jew.

“I shall pulverize you,” Bernstein reportedly warned Maurois. “I know how to hate. I shall ruin you. I shall isolate you. I shall reduce you to a position of

helplessness.” Such were the threats of

one noted French author against another, the two of them wartime refugees in

New York, and both Jewish. Nor was

Bernstein’s an idle threat. He quickly

launched a barrage of attacks on Maurois in the French-language press of the

U.S. and Canada, and spread rumors that Maurois was a Vichy sympathizer, a

fascist, a foe of the British, and an anti-Semitic Jew. What was this all about?

The collapse of France in the spring of

1940 had brought the end of the Third Republic and the installation, in that

part of France not occupied by the Germans, of the right-wing Vichy regime, with

Marshal Philippe Pétain, a venerable hero of World War I, as its head. But even as the Vichy government told the

French they must adjust to German hegemony in Europe and, in effect, make nice

with Hitler, General Charles De Gaulle had launched the Free French movement in

Great Britain so as continue the war against Germany. Every French citizen – and above all the

intellectuals, to whom many looked for guidance -- had to choose between Vichy

and De Gaulle, the newly established regime and the rebel. This conflict could assume a ferocity even

among the French exiles in New York.

| Henri Bernstein |

For Bernstein, coming to the U.S. was

easy: his mother was American, he had wealthy in-laws here, he spoke English

fluently and had visited here often. And

getting out of France was necessary, since he was Jewish. Only days after the Germans marched into

Paris in June 1940, he left for England and sailed from there to New York. Over here he lived sumptuously in the Waldorf

Astoria, with a sampling of his art collection on the walls, including a Manet

painting and a Toulouse-Lautrec drawing.

A notorious womanizer, he took up with Eve Curie, the daughter of the

Curies of radium fame, and then with a popular singer. But when it came to politics and the war he

was a passionate supporter of De Gaulle, on whose behalf he wrote articles for

the New York Times and New York Herald Tribune and other

leading newspapers. After the war he

returned to France and continued writing plays until his death in 1953.

| André Maurois, with a picture of Balzac on the wall behind him. |

And Maurois? Also a Jew (he was born Emile Herzog), he had

done liaison work with the British army in World War I, making many British

friends, and had lectured in the U.S. and as a result entertained a very

positive feeling for the U.S. and its citizens.

In 1938 he was elected to the Académie Française, an honor coveted by

some and scorned by others among the French intelligentsia. Then, in June 1940, before the Germans

entered Paris, the French army sent him on a mission to England, where De

Gaulle tried to enlist him as a propagandist addressing the French from

London. He declined, fearing for the

safety of his family back in France, but also out of loyalty to Pétain, for

whom he felt respect and affection.

Instead, now demobilized, he accepted an invitation to give lectures in

the U.S. and set sail with his wife for New York, where the managers of posh

hotels, knowing him from previous visits, were glad to welcome him, assuring

him he needn’t worry about paying until he had earned some money in America. He and his wife stayed first at the Plaza,

and then in a small apartment on the 17th floor of the Ritz

Towers. Invitations for weekends in the

country followed. As I have noted

before, it pays to have connections, and Maurois had many.

But comfy living was no defense against

Bernstein’s attacks. When Maurois wrote

an article for Life magazine

stressing how the French loved Pétain and asserting – sincerely, no doubt, but erroneously

– that the Marshal’s more controversial measures had been taken under duress,

it could only have stoked Bernstein’s anger and intensified his hostility. Hence the two slaps in the hotel lobby, and

the outpouring of threats and hate. Maurois

was by nature a moderate who could see more than one side to an issue, and in

wartime moderates are not in great demand.

Though deeply hurt by Bernstein’s attacks,

Maurois lectured extensively throughout the U.S., stressing the menace of Nazi

Germany to an America that was still technically neutral, and trying to

convince skeptical audiences that France’s collapse was the result only of

military inadequacies, and not of moral decadence, corruption, and

defeatism. In New York he socialized widely

with Saint-Exupéry, Romains, and other French refugees, and numerous American

friends as well, and even had a chat with Eleanor Roosevelt, who appreciated

the positive effect of his lectures.

When the U.S. entered the war, Maurois played

a more active role in the struggle, going with his friend Saint-Exupéry to join

the Free French forces in North Africa, though what he did there isn’t clear. After the war he rejoined his wife in New

York, taught French literature at the University of Kansas City, Missouri,

where he imparted to the children of those middle regions, so rich in corn and

hogs, the glories of Proust and Balzac.

When he returned to Paris in 1946, he found that his apartment on the

Boulevard Maurice Barrès had been occupied by the nephew of Herman Goering, who

on departing had ordered all Maurois’s books removed or destroyed, the

furniture mutilated, the Aubusson and oriental rugs torn, and the paintings

carried off. Maurois was crushed by the

loss especially of his books and rare papers.

It would take him five years to reconstitute the library.

| Jules Romains |

Another French refugee in New York was the

novelist Jules Romains, whose decision to leave France was motivated in part by

the desire to protect his wife, who was Jewish.

Sailing from Lisbon, they arrived in New York in July 1940 and took a low-priced

room at the Algonquin Hotel on West 44th Street, a famous gathering place for writers,

journalists, and critics, where the management, knowing who their new guests

were, upgraded them to a suite. Then

they moved to the Hotel Mayflower on Central Park West at 61st

Street, where they ended up in a penthouse with a shared terrace: another

example of the advantage of being preceded by one’s reputation and having the

right connections. In New York the

French exiles were not skimping along in a garret, picturesque as that might

have been.

Romains’s political views were not likely

to please Bernstein, who was busy demolishing the image of Pétain that Maurois

at first tried to preserve. A pacifist

who had avoided military service in World War I, Romains had argued in the

postwar years that only a reconciliation between France and Germany could bring

lasting peace in Europe. This point of

view, which might have been laudable in the years following World War II, was,

to put it mildly, misguided and deplorable when he maintained it after Hitler’s

rise to power. But Bernstein never

attacked him with the vehemence he showed to Maurois. Romains participated in Voice of America radio

broadcasts, then in 1941 went to Mexico, where he had many friends, to join

with other French refugees in founding the Institut Français d’Amérique

Latine. By now he was done with pacifism

and gave lectures attacking Vichy. When peace came he returned to France, where

he was elected to the Académie Française in 1946.

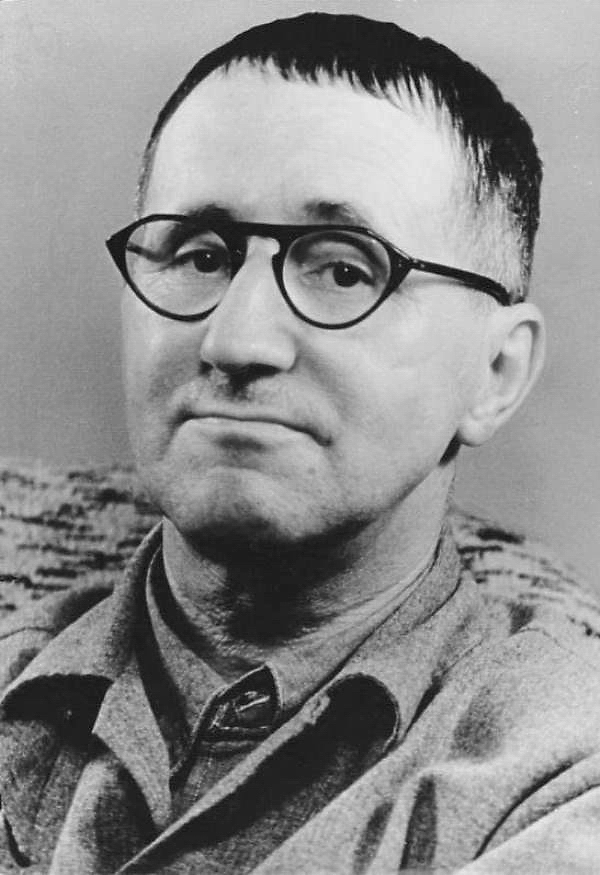

Bertolt Brecht

|

| Brecht, looking like a son of the people. Bundesarchiv |

The fiercely anti-fascist German playwright Bertolt

Brecht had collaborated with the composer Kurt Weill to create The Threepenny Opera (1928) and Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny (1930),

both of which, savagely critical of capitalism, were great successes despite

the vehement protests of Nazis in the audience.

When Hitler came to power in 1933, Brecht left Germany, lived for a

while in Denmark, and in July 1941, with his wife and harem (he always had a

harem) came to the United States, where he wrote some of his most famous

plays. An American who met him in New

York in 1946 described him as a short, wiry man with close-cropped hair and a

thin, bony face with a stubble of beard.

Brecht, he reported, talked with a flow of nervous energy, his eyes

sparkling with a wry sense of humor, as he radiated a great force of will that

made him seem much younger than his age of 48.

And he smoked cheap cigars.

Others were less generous, finding Brecht

contentiously arrogant, manipulative, and even, since he disliked bathing,

smelly. Thomas Mann called him a gifted

monster, and W. H. Auden, with whom he collaborated, remarked that Brecht was

one of the few people on whom a death sentence might be justifiably carried

out. Though born into a comfortably middle-class German family, in photographs

he always managed to look “proletarian” – close-cropped hair, plain clothes,

grim-faced or with a faint, sly smile -- and in so doing repeated the gesture

of Walt Whitman who, in the 1850s, presented himself to his readers as

working-class and “one of the roughs,” a parallel that Brecht, had he been

aware of it, would probably have rejected with disdain.

Though clearly an exile, Brecht was not

really an exile in New York, which he visited occasionally, since he settled

down in Hollywood -- the most curious of locales for an avowed Marxist in

proletarian garb -- and then in Santa Monica.

While still in Germany Brecht had known the U.S. chiefly through film

and fantasy, and the names of its cities and states had had a certain exotic

allure; now he could experience first-hand the glories and horrors of this

bastion of capitalism. The U.S., for

Brecht, was ignoble and loathsome, and Southern California a “Tahiti in

metropolitan form” where the air was unbreathable and there was nothing to

smell. Why was he there at all? Presumably because of the climate, the

presence of a German-speaking community of fellow exiles (Brecht never learned

English), and the possibility of making money in Hollywood (which he never

did).

When the Cold War took hold, Brecht’s

avowed Marxism got him into trouble.

Summoned before the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1947, he

testified that he had never been a member of the Communist Party, but smoked an

acrid cigar that made some of the committee members slightly sick; the very

next day he left the U.S. for Europe. In

1949 the offer of his own theater where he could fully realize his vision of

epic theater induced him to return to Berlin, but to East Berlin in

Communist-ruled East Germany, where his Berliner Ensemble became

world-famous. A canny Marxist, he

retained his Austrian passport while in East Germany and stashed the money from

the Stalin Peace Prize, which he received in 1955, in a Swiss bank

account. His detractors are quick to

point out that he never denounced Stalin’s atrocities or the oppressiveness of

the East German regime, but he influenced U.S. and European theater to a

remarkable extent. He died of a heart

attack in 1956 and is buried in Berlin.

Kurt Weill and Lotte Lenya

| Goggle glasses and a patterned bow tie perched at his throat like a butterfly: most definitely a bourgeois. Bundesarchiv |

The German composer Kurt Weill was born

into a middle-class Jewish family and was composing music by the age of thirteen. Photos show him, young or old, as a good

bourgeois, serious, unsmiling, tightly buttoned and neat, with glasses – a far

cry from Brecht’s proletarian (or pseudo-proletarian) image. In 1924 he met Lotte Lenya (an assumed stage

name), an actress of Viennese working-class origins, whom he married in

1926. Though no classic beauty, as an

actress and singer she had great stage presence, an untrained soprano voice

that was unforgettable, and a raw, gutsy quality that suited perfectly the work

of Weill and his collaborator Brecht, and that brought her instant fame in the

role of Jenny in The Threepenny Opera (1928). Though hard to classify – opera, musical, or

play with music? -- this work, an adaptation of John Gay’s Beggar’s Opera (1728), was an immediate success, treating audiences

to a world of thieves, murderers, and prostitutes that shocked and fascinated

them. By 1933 it had been translated

into 18 languages and performed more than 10,000 times on European stages.

|

| Not a great beauty, but incredibly dynamic on the stage, unforgettable. |

In spite of this success, Brecht and Weill

soon distanced themselves from each other, primarily because, by 1929, Brecht’s

ideas were tinged more and more with Marxism, and he was becoming increasingly

opinionated and dictatorial. The rise of

Hitler’s National Socialist Party put Brecht, Weill, and Lenya in danger, since

they were known leftists and Weill was Jewish.

Lenya was now living with the singer Otto Pasetti, and early in 1933 she

initiated divorce proceedings against Weill, which may have been in part a

tactical move, since it would let her reclaim some of his assets that might

otherwise be seized by the Nazis. When

Hitler came to power in March of that year, Weill and Lenya fled Germany

separately. The pending divorce did not

keep Lenya from performing in Brecht and Weill’s sung ballet (ballet chanté) The Seven Deadly Sins, which opened in Paris in June 1933 to mixed

reviews and would be Brecht and Weill’s last collaboration. Three months later Lenya and Weill’s divorce

became final. But by sometime in 1934

Lenya’s affair with Pasetti was over, and after a brief fling with the

Surrealist artist Max Ernst, she became reconciled with Weill, who had been

having an affair of his own with Erika Neher, the wife of the renowned set

designer Caspar Neher, who worked closely with Brecht. In spite of their infidelities, Weill and

Lenya always remained friends and collaborators and finally resumed their

relationship. Even in free-living

artistic circles old friends, it seems, are best.

In September 1935 the, dare we say, happy

couple came to New York, residing first at the St. Moritz Hotel on Central Park

South (not exactly a refuge for the impecunious) and later in an apartment at

231 East 62nd Street; they married again in January 1937. Convinced that his scores in Germany had been

destroyed by the Nazis, Weill broke dramatically with his German past, speaking

and writing German rarely, and studying American popular music so as to create

works completely different from what he had done in Germany. Unlike Brecht, he and Lenya adapted to the

capitalist American society and prospered.

His American works never matched the earlier ones in bite, but some of

his creations, notably “September Song,” had remarkable success. There are those who argue that his American

career was not a sharp break with his past, but simply a new phase of it, but

I’m not convinced. It’s quite a leap

from “Mack the Knife” to “September Song,” and I can’t believe that any of the

Broadway musicals he helped create had the keen edge of The Threepenny Opera, where Mack the Knife pronounces, “What is the

robbing of a bank, compared to the founding of one?” (a statement that might

well have resonance today).

Weill and Lenya moved into a house of

their own in New City, Rockland County, in May 1941. He became a U.S. citizen in 1943 and died of

a heart attack in a New York hospital soon after his fiftieth birthday on April

3, 1950; for weeks afterward, Lenya was so distraught that neighbors were

afraid to let her stay alone at night.

Despite the off-and-on infidelities, her life had been intimately linked

to his ever since their first meeting in 1924.

The second time I saw Threepenny I was fully rested and alert, and confirmed my first

impression that this was a remarkable event, and her now husky voice

inimitable. From then on I was a devoted

fan of anything that Brecht and Weill had worked on together, and anything that

Lotte Lenya sang or performed in; she became a part of my New York

experience. I will never forget her

rendering of the song “Pirate Jenny” in The

Threepenny Opera, where she plays a lowly and exploited hotel maid who

imagines a pirate ship coming into the harbor to avenge her; when the pirates

ask if she should kill some or all of the people, she answers tersely, in the

German version, “Alle,” in that one short word conveying unforgettably the

resentment and hatred toward their masters of the downcast and oppressed.

In the 1950s “Mack the Knife” became

popular in the U.S.; you couldn’t avoid it.

I loved the song but was troubled by its new status as a hit show tune

that every pop singer wanted to have a crack at; divorced from its context in The Threepenny Opera, it was less

sinister, less haunting.

Another New York triumph for Lotte Lenya

was George Balanchine’s City Ballet production of The Seven Deadly Sins, newly translated by W. H. Auden and Chester

Kallman, which opened in December 1958. The main character, Anna, is presented as a split personality. Lenya had the

speaking and acting role, the rational Anna, her face framed by orange hair and

bangs, with bold red lips and garish mascara, a grotesque appearance suggesting figures out of German Expressionism, the flagrant streetwalkers of Kirchner or the caricatures of Gross. The dancing role was performed by Allegra Kent, who would experience

the seven sins in seven cities of a mythological America. By way of introduction Lenya informed the

audience in her inimitable down-to-earth voice, with a glance at the lovely

young dancer, “She’s the good-looking one; I’m practical.” In the original 1933 production by George Balanchine

in Paris, Lenya had done the same role with Tilly Losch as the dancer, with the

two of them about the same age and Losch bearing a remarkable resemblance to

Lenya. In this New York production the

fact that Lenya was 60 and Kent a mere 21 seemed irrelevant, given Lenya’s effectiveness in the role. As the two Annas seek their fortune and

encounter the seven deadly sins in the cities of America, a male quartet (with

the mother a bass in drag, another grotesque Expressionist touch) watch smugly and receive their earnings, which they

use to gradually build a little house for themselves. Needless to say, the quartet represents the

capitalist bourgeoisie exploiting the

labor of workers. I’ll never forget the

quartet’s insistent repetition:

Lazy

bones are for the Devil’s stockpot.

Lazy bones are for the Devil’s stockpot.

I saw the ballet twice and

was overwhelmed by it. Amazingly, it was

not revived by City Ballet until 2011.

From 1960 on Lenya lived in an apartment

at 404 East 55th Street in New York.

In 1961 she appeared in the movie version of Tennessee Williams’s The Roman Spring of Mrs. Stone as the

enterprising Contessa who helps Vivian Leigh find a young Roman lover; for her

performance Lenya was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Supporting

Actress. She would marry again three

times but, being determined to promote the works of her deceased husband, in

1962 she created the Kurt Weill Foundation for Music and oversaw vigilantly the

revivals of his works, even to the point of attending rehearsals script in hand

and following the performers line by line.

More performances and recordings followed, and more honors. Keeper of the flame even when her own life

was sputtering out, in her last days she embraced the acclaimed opera singer

Teresa Stratas as her successor in keeping Weill’s music alive. Stratas moved in with her to see her through

her last days as she succumbed to cancer.

Lenya died on November 27, 1981, aged 83, and was buried beside Weill in

Haverstraw, New York.

Source note: For information on Bernstein, Maurois, and

Romains in New York, I am indebted to my longtime friend and comrade in the

study and appreciation of French literature and culture, Jeanine

Parisier-Plottel. Bernstein’s attack on

Maurois is recounted in Maurois’s Mémoires;

though Maurois doesn’t identify his attacker by name, it is obviously

Bernstein.

This is New York

|

| Jorge Royan |

Coming soon: A post on Remarkable Women: a prostitute’s

daughter who slept in an empress’s bed, married and divorced an ex-vice

president, and hobnobbed with ex-kings and a future emperor.

©

2014 Clifford Browder

Thank you for the interesting history lesson, I didn't know much about NYC and I've recently fallen in love with it. It's culture and atmosphere is one of the most unique things in the USA. I'm currently trying to find its rate on http://new-york.hotelscheap.org/times-square.html but I somehow can't find it. I suppose it isn't exactly cheap, but I hope it won't be a rip-off.

ReplyDeleteB&Bs are probably the bargain option. No, New York isn't cheap. Hope you enjoy this crazy, fascinating place.

Deleteमहाकालसंहिता कामकलाकाली खण्ड पटल १५ - ameya jaywant narvekar कामकलाकाल्याः प्राणायुताक्षरी मन्त्रः JANUARY 2026

ReplyDeleteओं ऐं ह्रीं श्रीं ह्रीं क्लीं हूं छूीं स्त्रीं फ्रें क्रों क्षौं आं स्फों स्वाहा कामकलाकालि, ह्रीं क्रीं ह्रीं ह्रीं ह्रीं हूं हूं ह्रीं ह्रीं ह्रीं क्रीं क्रीं क्रीं ठः ठः दक्षिणकालिके, ऐं क्रीं ह्रीं हूं स्त्री फ्रे स्त्रीं ख भद्रकालि हूं हूं फट् फट् नमः स्वाहा भद्रकालि ओं ह्रीं ह्रीं हूं हूं भगवति श्मशानकालि नरकङ्कालमालाधारिणि ह्रीं क्रीं कुणपभोजिनि फ्रें फ्रें स्वाहा श्मशानकालि क्रीं हूं ह्रीं स्त्रीं श्रीं क्लीं फट् स्वाहा कालकालि, ओं फ्रें सिद्धिकरालि ह्रीं ह्रीं हूं स्त्रीं फ्रें नमः स्वाहा गुह्यकालि, ओं ओं हूं ह्रीं फ्रें छ्रीं स्त्रीं श्रीं क्रों नमो धनकाल्यै विकरालरूपिणि धनं देहि देहि दापय दापय क्षं क्षां क्षिं क्षीं क्षं क्षं क्षं क्षं क्ष्लं क्ष क्ष क्ष क्ष क्षः क्रों क्रोः आं ह्रीं ह्रीं हूं हूं नमो नमः फट् स्वाहा धनकालिके, ओं ऐं क्लीं ह्रीं हूं सिद्धिकाल्यै नमः सिद्धिकालि, ह्रीं चण्डाट्टहासनि जगद्ग्रसनकारिणि नरमुण्डमालिनि चण्डकालिके क्लीं श्रीं हूं फ्रें स्त्रीं छ्रीं फट् फट् स्वाहा चण्डकालिके नमः कमलवासिन्यै स्वाहालक्ष्मि ओं श्रीं ह्रीं श्रीं कमले कमलालये प्रसीद प्रसीद श्रीं ह्रीं श्री महालक्ष्म्यै नमः महालक्ष्मि, ह्रीं नमो भगवति माहेश्वरि अन्नपूर्णे स्वाहा अन्नपूर्णे, ओं ह्रीं हूं उत्तिष्ठपुरुषि किं स्वपिषि भयं मे समुपस्थितं यदि शक्यमशक्यं वा क्रोधदुर्गे भगवति शमय स्वाहा हूं ह्रीं ओं, वनदुर्गे ह्रीं स्फुर स्फुर प्रस्फुर प्रस्फुर घोरघोरतरतनुरूपे चट चट प्रचट प्रचट कह कह रम रम बन्ध बन्ध घातय घातय हूं फट् विजयाघोरे, ह्रीं पद्मावति स्वाहा पद्मावति, महिषमर्दिनि स्वाहा महिषमर्दिनि, ओं दुर्गे दुर्गे रक्षिणि स्वाहा जयदुर्गे, ओं ह्रीं दुं दुर्गायै स्वाहा, ऐं ह्रीं श्रीं ओं नमो भगवत मातङ्गेश्वरि सर्वस्त्रीपुरुषवशङ्करि सर्वदुष्टमृगवशङ्करि सर्वग्रहवशङ्करि सर्वसत्त्ववशङ्कर सर्वजनमनोहरि सर्वमुखरञ्जिनि सर्वराजवशङ्करि ameya jaywant narvekar सर्वलोकममुं मे वशमानय स्वाहा, राजमातङ्ग उच्छिष्टमातङ्गिनि हूं ह्रीं ओं क्लीं स्वाहा उच्छिष्टमातङ्गि, उच्छिष्टचाण्डालिनि सुमुखि देवि महापिशाचिनि ह्रीं ठः ठः ठः उच्छिष्टचाण्डालिनि, ओं ह्रीं बगलामुखि सर्वदुष्टानां मुखं वाचं स्त म्भय जिह्वां कीलय कीलय बुद्धिं नाशय ह्रीं ओं स्वाहा बगले, ऐं श्रीं ह्रीं क्लीं धनलक्ष्मि ओं ह्रीं ऐं ह्रीं ओं सरस्वत्यै नमः सरस्वति, आ ह्रीं हूं भुवनेश्वरि, ओं ह्रीं श्रीं हूं क्लीं आं अश्वारूढायै फट् फट् स्वाहा अश्वारूढे, ओं ऐं ह्रीं नित्यक्लिन्ने मदद्रवे ऐं ह्रीं स्वाहा नित्यक्लिन्ने । स्त्रीं क्षमकलह्रहसयूं.... (बालाकूट)... (बगलाकूट )... ( त्वरिताकूट) जय भैरवि श्रीं ह्रीं ऐं ब्लूं ग्लौः अं आं इं राजदेवि राजलक्ष्मि ग्लं ग्लां ग्लिं ग्लीं ग्लुं ग्लूं ग्लं ग्लं ग्लू ग्लें ग्लैं ग्लों ग्लौं ग्ल: क्लीं श्रीं श्रीं ऐं ह्रीं क्लीं पौं राजराजेश्वरि ज्वल ज्वल शूलिनि दुष्टग्रहं ग्रस स्वाहा शूलिनि, ह्रीं महाचण्डयोगेश्वरि श्रीं श्रीं श्रीं फट् फट् फट् फट् फट् जय महाचण्ड- योगेश्वरि, श्रीं ह्रीं क्लीं प्लूं ऐं ह्रीं क्लीं पौं क्षीं क्लीं सिद्धिलक्ष्म्यै नमः क्लीं पौं ह्रीं ऐं राज्यसिद्धिलक्ष्मि ओं क्रः हूं आं क्रों स्त्रीं हूं क्षौं ह्रां फट्... ( त्वरिताकूट )... (नक्षत्र- कूट )... सकहलमक्षखवूं ... ( ग्रहकूट )... म्लकहक्षरस्त्री... (काम्यकूट)... यम्लवी... (पार्श्वकूट)... (कामकूट)... ग्लक्षकमहव्यऊं हहव्यकऊं मफ़लहलहखफूं म्लव्य्रवऊं.... (शङ्खकूट )... म्लक्षकसहहूं क्षम्लब्रसहस्हक्षक्लस्त्रीं रक्षलहमसहकब्रूं... (मत्स्यकूट ).... (त्रिशूलकूट)... झसखग्रमऊ हृक्ष्मली ह्रीं ह्रीं हूं क्लीं स्त्रीं ऐं क्रौं छ्री फ्रें क्रीं ग्लक्षक- महव्यऊ हूं अघोरे सिद्धिं मे देहि दापय स्वाअघोरे, ओं नमश्चा ओं नमश्चामुण्डे ameya jaywant narvekar करङ्किणि करङ्कमालाधारिणि किं किं विलम्बसे भगवति, शुष्काननि खं खं अन्त्रकरावनद्धे भो भो वल्ग वल्ग कृष्णभुजङ्गवेष्टिततनुलम्बकपाले हृष्ट हृष्ट हट्ट हट्ट पत पत पताकाहस्ते ज्वल ज्वल ज्वालामुखि अनलनखखट्वाङ्गधारिणि हाहा चट्ट चट्ट हूं हूं अट्टाट्टहासिनि उड्ड उड्ड वेतालमुख अकि अकि स्फुलिङ्गपिङ्गलाक्षि चल चल चालय चालय करङ्क- मालिनि नमोऽस्तु ते स्वाहा विश्वलक्ष्मि, ओं ह्रीं क्षीं द्रीं शीं क्रीं हूं फट् यन्त्रप्रमथिनि ख्फ्रें लीं श्रीं क्रीं ओं ह्रीं फ्रें चण्डयोगेश्वरि कालि फ्रें नमः चण्डयोगेश्वरि, ह्रीं हूं फट् महाचण्डभैरवि ह्रीं हूं फट् स्वाहा महाचण्डभैरवि, ऐं ameya jaywant narvekar