For a press release of my new novel, Bill Hope: His Story, go here. This is the second title in my Metropolis series of historical novels set in nineteenth-century New York. The first in the series is The Pleasuring of Men (Gival Press, 2011), mention of which appears at the end of this post.

Bill Hope can be ordered from Amazon and will be shipped after the release date of May 17, 2017. But the paperback, which goes for $20, will cost an additional $4.95 for shipping, unless you order books totaling $25 or more. The book is also available now from the author and will be mailed immediately ($20 + postage).

For readers who like historical fiction and a fast-moving story.

And now, on to poesie.

For readers who like historical fiction and a fast-moving story.

And now, on to poesie.

* * * * * * * *

I

hate poetry, and I’m not the only one.

“I, too, dislike it,” says renowned poet Marianne Moore (in her lifetime,

a fellow West Village resident) in her much-quoted poem “Poetry,” which

continues, “there are things / that are important beyond all this fiddle.” But then, of course, she goes on to hedge her

bet:

Reading it, however, with a

perfect

contempt for it, one

discovers in

it after all, a place for the

genuine.

And so on, and so on. What, after all, would you expect from a

poet? A total, absolute, and scathing

rejection of the stuff? Does a baker

hate bread, or an alcoholic hate booze?

Of course she loves poetry, can’t get off it. But the deliberate prosiness of her lines

undermines her intention; her “Poetry” is just prose chopped up in short lines

to look like poetry. Poets, please note,

are cunning.

These thoughts and those that follow were inspired by poet

Charles Simic’s review of Ben Lerner’s The

Hatred of Poetry (a title that warms me to the cockles of my heart) in The New York Review of Books of April 6,

2017. At the start of the review is an

English translation of two lines of the Roman poet Martial, who is famous for

his biting, pithy satire. (Martial’s

sting is probably lost in translation.)

Don’t let the boy just loaf about:

If he writes verses, kick him out.

That the review is written by

a poet, and a well-known one at that, is a fair indication that the reviewer

will differ with the author reviewed, and the same might be said of this post,

written by a self-confessed poet with shiny words on his tongue and rancor in

his heart. Moral:

On the subject of poetry, never trust a poet.

Simic goes on to recall Shelley’s deluded assertion that poetry is

“something divine,” countered by poet Molly Peacock’s reminder that while bread

is necessary, poetry is not -- at least, not in the way that bread is. Simic also cites Plato’s famous denunciation

of poets for passing off their fantasies as truth, for which he banished them

from his ideal Republic. (We

won’t dwell on the fact that Plato himself was, at moments, a brilliant

poet and visionary, albeit in

prose.) With both Molly and Plato, I

heartily agree. And it’s still a common and

justifiable belief that poets aren’t right in the head, for why else would they

choose a lifetime of poverty and ridicule? In this regard, right on, Mr. Simic, right on! Maybe we can trust you after all … maybe.

|

Percy Bysshe Shelley. With a name like that

he'd have to be a poet, the ethereal style.

|

Also on the side of the anti-poets, and cited by Simic, is

the Polish author Witold Gombrowicz, who in his essay “Against Poets” insists

that no one really gives a damn about poetry, even though they pretend that

they do. I’m not familiar with Mr.

Gombrowicz’s works and can’t even pronounce his name, but once again, I

applaud. Sugar, he suggests, is good for

sweetening coffee, but not for eating by the spoonful; excess of poetry, plus

the sentiment and piety that go with it, can be wearying. Having in my time read a vast deal of

mediocre poetry – poetry that aspired to lift me to the heights, but often dumped

me in the dumpiest of dumps – I continue to applaud.

Simic finally gets to Ben Lerner’s book, The Hatred of Poetry, which observes that poetry is often met with

contempt, rather than mere indifference, and is often denounced, rather than

simply dismissed. True enough, says

Simic, but it’s because the critics were frightened off it in school. But he takes more seriously Lerner’s

contention that poets today are too self-involved, too apolitical, too

indifferent to the social woes around them, and therefore out of touch with the

rest of us.

Enough of Simic; what does Browder think? Be warned: from at least fifth grade on I was

scribbling something or other; I was Literature in an eighth-grade morality

play about Every Youth; and by high school I was exuding scraps of poetry now

mercifully consigned to oblivion.

On the subject of poetry, never trust a poet.

Since then, off and on, I

have dabbled, and even more than dabbled, in concocting the stuff, propelled less

by genius or an avowed sense of mission than by a gut instinct, a totally

irrational urge to use and misuse words, for which I have received –

deservedly, no doubt – scant recognition or reward. I will say that a lot of the rejection letters these days are anything but blunt; in saying no, they almost have tears in their eyes. I don’t complain about rejections, since this is the lot of

most poetic scribblers, and the lack of recognition arms me for my fight

against the very urge itself, and for periodic bouts of self-contempt not for

myself overall, but for myself as – alas! – a poet. If there were a twelve-step program for

recovering poets (“Poets Anonymous”?), I would join it.

And why shouldn’t we hate poetry? The stuff is

· Sticky, icky, gooey with feeling

· Pretentious

· Often obscure

· Concerned with flighty little moments of experience –

i.e., with trivia

· Written by eccentrics, flops, and perverts

· Read mostly by old-maid librarians and schoolteachers

(usually frustrated poets themselves), and an assortment of unmanly dainty

types and hypersensitive freaks

· Profitless

· Time-consuming

· Addictive

· And above all, irrelevant.

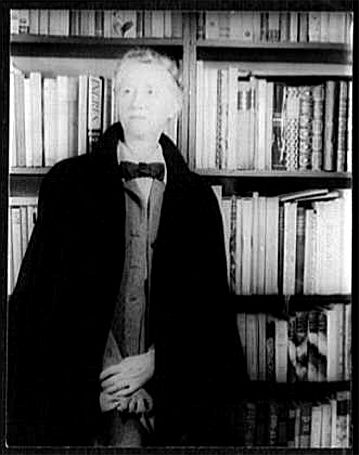

To round it off, just consider the photo of Marianne Moore

accompanying the review: an elderly woman in a broad-brimmed hat and a flowing

black cape, smiling at a plumed white cockatoo perched on her wrist. Oddball, weirdo, eccentric! Case closed.

|

| Here she is, black-caped, minus hat and cockatoo. The magisterial style, beloved of feminists. |

But of course it never is.

Back in the nineteenth century, middle-class citizens of this and many

cities had a poetry shelf in their libraries that they replenished with

purchases from time to time. Who were

they reading? Not Whitman and Dickinson,

whom we have since enshrined. No, they

were reading such stalwarts of poesy as Longfellow, Whittier, Tennyson, and

Browning. Late in the century Browning

became such a rage that Browning Societies sprang up all over the country,

dedicated to reading his weighty and impenetrable later poems and teasing

meaning out of them. When Longfellow’s

lengthy poem Evangeline was published

in 1847, there were lines around the block as eager readers flocked to get it,

and as late as 1941 it was still being inflicted upon eighth graders, I being

one of them, to the point that the opening line, “This is the forest primeval. The murmuring pines and the hemlocks,” is

imprinted in my mind. As for his other epic, The Song of Hiawatha, I'll simply quote the opening lines:

By the shores of Gitchee Gumee,

By the shining Big-Sea-Water,

Stood the wigwam of Nokomis,

Daughter of the Moon, Nokomis...

"Gitchee Gumee," if it matters, is Longfellow's rendition of the Chippewa name for Lake Superior. As for the meter, never has trochaic tetrameter been so abused.

Yes, back then people used to read poems, even long ones set in Gitchee Gumee, but such is not the case today. Once,

when reading a biography of the Russian writer Pushkin, I encountered a

description of a trip of his to the Caucasus, where he entered a village

recently wrested by the Russians from the Turks. Meeting an old man in the village, he talked

with him – I don’t recall in what language – and happened to mention that he was a poet. The old man looked at him with awe: “Blessed

is the day when I meet a poet!” Such an

utterance gives an insight into another society where poetry is not merely tolerated

but honored, a society in sharp contrast to our own.

It’s tempting to say that no one really reads poetry in this

country today except poets, who usually think their own stuff better. But that’s not quite the case. First of all, the poetry reading scene in New

York City is hot, hot, hot – readings

all over the place. That, of course, is

New York, a quirky, trendy place full of oddballs, and in no way typical of the

nation. But there are small presses that

– God help them! – specialize in publishing the stuff, and they claim to be so

swamped with submissions that they have to shut their submission portal until

further notice, or charge a submission fee, or publish only the winner of a

contest whose submission fee is often twenty or twenty-five dollars. (Ah, those contests: to make one poet happy,

you have to make four hundred others unhappy, even while sucking in their

moolah.)

|

E. E. Cummings, a 20th-century poet, the slouchy

style -- quite a contrast with Shelley. They come in all sizes and shapes. |

Which brings us to “po biz,” the business of poetry, a scene

where allegedly starving poets compete for juicy awards and fellowships, and

try desperately to get a paid position teaching poetry writing at some delusional

institution of higher learning. And why

those classes? Because today everybody

wants to be a poet, just as everybody wants to be a playwright or novelist or

whatever, and canny operators are taking full advantage and raking in millions

… or at least a few thousand, enough to keep their precarious operation afloat. And it’s not just kids; a friend of mine, an

accomplished poet, also teaches retired businessmen who always wanted to write

poetry and now indulge themselves, paying a hefty fee in spite of their deplorable lack of

talent. The poetry bug lurks deep in the

innards of many of us, like a microbe for which there is no cure.

Conclusion: yes,

poetry and poets exist today, and po biz is exploiting would-be poetasters with

diligence and cunning. We need accountants

and bricklayers and exterminators and garbage collectors, and what do we

get? Poets. Thousands of them, scribbling away. Which is one more reason why I and so many

other sane and clearheaded individuals hate poetry.

On the subject of poetry, never trust a poet.

Toward the end of his lengthy review, Simic tells how in the

rowdy late 1960s he participated in the Poets in the Schools program in New

York City. Broke, he did it to snag the

measly fifty bucks a day that it paid.

(Starving poets again -- what folly!)

Going to the principal’s office, he would find a guide waiting there to

escort him through unruly hallways to a classroom where equal pandemonium

reigned. The teacher then silenced the

kids by shouting, “We have a poet with us today!” Confusion as the kids looked wonderingly at

each other, not sure they had heard her right.

A poet? Here? Now?

Disbelief.

“Do you like poetry?” Simic asked.

They shook their heads, some pretended to gag, and one or

two spat in disgust.

Undaunted, Simic asked, “Have you ever written a love

letter?”

Embarrassed silence; obviously, they had.

“Would you like to hear a love poem?”

Silence signifies assent.

So Simic read them some poems by e e cummings (aka E. E. Cummings), Emily Dickinson, Edna St.

Vincent Millay, and others, each time asking if they wanted to hear more; they

did. Then he read poems on other

subjects, and they listened with great attention and began making perceptive

remarks. After class a few even lingered

to ask where they could find one of the poems he had read. End of story.

Please notice how the clever Simic, greedy for a buck,

manipulated these malleable young minds – a maneuver that he boasts – yes,

boasts! -- of having used effectively with college students as well. On this sorry note I will end.

On the subject of poetry, never trust a poet.

* * * * * *

* * * * * *

BROWDERBOOKS: No Place for Normal: New York / Stories from the Most Exciting City in the World, my selection of posts from this blog, has received these awards: the Tenth Annual National Indie Excellence Award for Regional Non-Fiction; first place in the Travel category of the 2015-2016 Reader Views Literary Awards; and Honorable Mention in the Culture category of the Eric Hoffer Book Awards for 2016. For the Reader Views review by Sheri Hoyte, go here.

If you love the city (or hate it), this may be the book for you. An award winner, it sold well at BookCon 2017.

As always, the book is available from Amazon and Barnes & Noble.

|

The Pleasuring of Men (Gival Press, 2011), the first novel in the Metropolis series, tells the story of a young male prostitute in the late 1860s in New York who falls in love with his most difficult client.

What was the gay scene like in nineteenth-century New York? Gay romance, if you like, but no porn (I don't do porn). Women have read it and reviewed it. (The cover illustration doesn't hurt.)

Likewise available from Amazon and Barnes & Noble.

Coming soon: What's in a name? The names for New York City, and where they come from.

© 2017 Clifford Browder