EXPOSURE FOR DARK KNOWLEDGE

Dark Knowledge (Anaphora Literary Press, 2018), the third novel in the Metropolis series. Adult and young adult. A fast-moving historical novel about New York City and the slave trade, with the sights and sounds and smells of the waterfront.

Available from Amazon and Barnes & Noble.

Dark Knowledge, my novel about the slave trade in New York, has appeared twice in August in the LibraryBub newsletter, which lists small-press and self-published books of interest to librarians. The newsletters were opened by librarians 4909 times, and the Amazon link for the book was clicked 409 times. Dark Knowledge, which I think of as historical fiction, was also listed in the Mystery & Thriller category in LibraryPub press releases picked up by NBC, ABC, and CBS.

To get word of future reviews, giveaways, and other news, sign up using the form in the sidebar on the right.

Dark Knowledge (Anaphora Literary Press, 2018), the third novel in the Metropolis series. Adult and young adult. A fast-moving historical novel about New York City and the slave trade, with the sights and sounds and smells of the waterfront.

For my other books, see BROWDERBOOKS following the post below.

Justice: Dorothy Day, a Devout and Rebellious Catholic

Raised a Protestant in a tranquil Republican suburb of Chicago during the Great Depression, I never heard of Dorothy Day or her movement, and when I heard of them later, it was only in a casual and superficial way. But if ever there was a person who gave her life to justice, in the form of justice for the working poor and the underprivileged, it was Dorothy Day. So who was she, and what was her movement

all about?

all about?

|

| Dorothy Day, 1916. |

She was Brooklyn-born to a family of nominal Protestants, and at age 14 became an Episcopalian while her family lived in Chicago. After two years at the University of Illinois, in 1916 she came to New York, settled on the Lower East Side, and worked for a series of socialist publications. She often covered radical activities in Union Square, where socialists, communists, anarchists, and the IWW (International Workers of the World, known as Wobblies) harangued and marched and demonstrated. At loose ends when one of her papers was shut down for criticizing the draft during World War I, she was recruited by a friend to join a women’s suffrage picket line in Washington, D.C., tangled there with the police, and at the tender age of 20 got arrested and ended up in a workhouse in Virginia where she was beaten and went on a 10-day hunger strike until released.

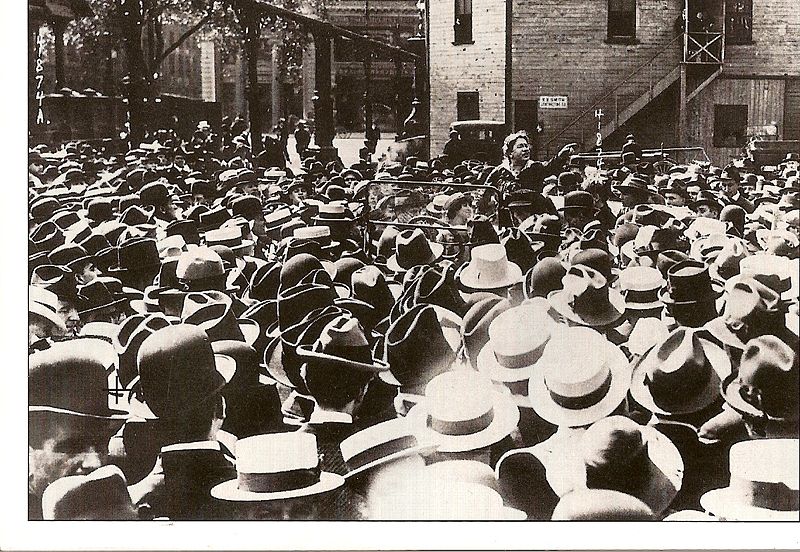

|

| The anarchist Emma Goldman addressing a rally in Union Square, 1916. Just the sort of event that Dorothy Day covered as a reporter. The hats suggest an all-male audience. |

In the raucous Greenwich Village scene of the time she was a pal of Eugene O’Neill, drinking rye whiskey straight with him in a bar called the Golden Swan, known endearingly to its patrons as the Hell Hole. Rubbing elbows there were gangsters, writers, artists, and other suspect and disreputable individuals, including the Hudson Dusters, a notorious local gang who admired Day for her ability to drink them silly. The raucous doings at the Hell Hole inspired paintings by John Sloan and Charles Demuth, and maybe also Harry Hope's saloon in O'Neill's The Iceman Cometh. When not cavorting at the Hell Hole, Day and her pals would pick up "interesting-looking strangers" in Washington Square Park and take them to dinner -- perhaps a first indication of her later concern for the poor.

Surviving failed love affairs and an abortion, in 1924 she bought a beach cottage in the Spanish Camp community on the South Shore of Staten Island that she used as a retreat for writing. Soon she fell in love with Forster Batterham, an atheist who didn’t believe in marriage, and in 1926 bore him a child, her daughter, Tamar. Though neither she nor Batterham was Catholic, she had her daughter baptized in the Catholic Church. She had long been drifting toward religion, stopping off daily for early-morning mass at St. Joseph's on Sixth Avenue near Waverly Place. What long held her back was fear of losing her atheist partner. Finally, with the help of a Sister of Charity who had befriended her, in 1927 she herself was baptized at a Catholic church in Tottenville, Staten Island, and became a practicing Catholic. Breaking with Batterham, in 1929 she left Staten Island and took her daughter with her to Los Angeles for a brief stint as a film writer, following which they returned to New York. Photos of her both before and after her conversion show a tall, thin young woman who wore little or no makeup and kept her hair cut short, always plain-faced and unsmiling: an appearance she may have cultivated, so as to avoid any hint of glamour or sex.

Surviving failed love affairs and an abortion, in 1924 she bought a beach cottage in the Spanish Camp community on the South Shore of Staten Island that she used as a retreat for writing. Soon she fell in love with Forster Batterham, an atheist who didn’t believe in marriage, and in 1926 bore him a child, her daughter, Tamar. Though neither she nor Batterham was Catholic, she had her daughter baptized in the Catholic Church. She had long been drifting toward religion, stopping off daily for early-morning mass at St. Joseph's on Sixth Avenue near Waverly Place. What long held her back was fear of losing her atheist partner. Finally, with the help of a Sister of Charity who had befriended her, in 1927 she herself was baptized at a Catholic church in Tottenville, Staten Island, and became a practicing Catholic. Breaking with Batterham, in 1929 she left Staten Island and took her daughter with her to Los Angeles for a brief stint as a film writer, following which they returned to New York. Photos of her both before and after her conversion show a tall, thin young woman who wore little or no makeup and kept her hair cut short, always plain-faced and unsmiling: an appearance she may have cultivated, so as to avoid any hint of glamour or sex.

|

| Dorothy Day, 1934. A touch of lipstick, perhaps, but a very earnest look. |

In December 1932, trying to be both activist and Catholic but not sure how these two sides of her life could interact, she met a Frenchman, Peter Maurin, a former Christian Brother, spiritual vagabond, and self-described peasant some 20 years her senior, who with a thick French accent preached to her in singsong monologues his version of the social teachings of Catholicism. Inspired by Saint Francis of Assisi, he lived a life of voluntary poverty and stressed the importance of building a new society where people could be good and therefore happy. A crank, said some, but Dorothy Day listened, and the Catholic Worker movement was born. Typically, it never occurred to her to ask a superior's permission; she simply saw a need and forged ahead to do something about it.

So it was that in 1933, in the very depths of the Great Depression, Dorothy Day and Peter Maurin started a monthly called the Catholic Worker. They handed it out at Union Square on May Day, where every species of radical was orating on a soap box, and hundreds of unemployed men, hungry and idle, were ready to listen to almost any program of action. Right next to the communists’ Daily Worker, they were touting the Catholic Worker, and its seemingly unprecedented social program for Catholics. Never one to hold back, she denounced "this rotten, decadent, putrid industrial capitalist system which breeds such suffering in the whited sepulcher of New York." Among those restless crowds there were plenty of Irish and Italians and other Catholics who listened. Within four months the new publication, offered at a penny a copy, had a circulation of 20,000, and with help from parishes that ordered bundles of it, within a year the circulation reached 100,000. In those early days their monthly sometimes failed to appear for lack of funds, but in time donations of food, clothes, and money began coming in.

|

| Peter Maurin, 1934. Hardly the look of a spiritual vagabond or peasant. |

Soon the destitute were showing up at their door. Since they talked about feeding the hungry and sheltering the homeless, said the callers, maybe they could feed and shelter them. So Day and Maurin started a soup line that got longer and longer, and lodged people wherever they could. Finally, in 1936, they were able to rent a whole building on Mott Street in Little Italy, on the Lower East Side, for their first “house of hospitality,” offering food and shelter to the poor. Word spread, and soon the soup line stretched down the street for blocks. Farms for communal living followed, and the movement spread to other cities, and finally even to Canada and Great Britain. But among those welcomed were cheats and drunks and troublemakers whom she had to tolerate with strained compassion – not easy for an activist who was anything but meek. And as she became famous, rumors circulated of her having visions or even the stigmata. These notions she dismissed with scorn, for there was work to do; no time for folderol.

During the Spanish Civil War of 1936-1939 she supported the anticlerical Republicans fighting Franco’s fascists, while the Church supported Franco – the first of many conflicts where she and the Church were at odds. Catholic churches, schools, and hospitals stopped distributing the Catholic Worker, and circulation fell from 150,000 to 30,000. “How could you become a Catholic?” many relatives and friends had asked her. In her first memoir, From Union Square to Rome (1938), without dwelling on her years of “grievous mortal sin,” she told how a series of events over many years had made her feel the need of religion. But in 1941, when the U.S. entered World War II, her pacifism brought her into conflict with the government, the draft, and everyone.

Conflict was her way of life: labor vs. capital, pacifism vs. war, radical action vs. the status quo, and Dorothy Day vs. Francis Spellman, the Cardinal Archbishop of New York. She had one foot in Catholicism, one in anarchism, and even one in communism, which is more feet than one person ought to have. Well into her ripe later years she was ready to write and demonstrate and picket, and endured at least eleven sojourns behind bars. Busy as she was, she had little time to raise her daughter, whom she left to others. Tamar married very young and had nine children, the youngest of whom would write a biography of her grandmother and say of Dorothy Day that, while she might tussle with authority, she never lost sight of the heart of the Church.

Tussle she did. In 1949, workers in Catholic cemeteries managed by the archdiocese of New York went on strike for better wages, and Cardinal Spellman labeled the union action "communist-inspired" and used seminarians to break the strike by digging graves. Employees of the Catholic Worker promptly joined the picket line, and Day wrote the cardinal informing him that he was "misinformed." Spellman ignored her plea to resolve the dispute, and the union was forced to accept the archdiocese's terms. The cardinal, Day insisted in the Catholic Worker, was "ill-advised" in using a show of force against a union of poor working men. The archbishop, she acknowledged, was the diocese's chief priest and confessor, but he was not her ruler.

The Cardinal Archbishop of New York was not used to being told that his actions were "misinformed" or "ill-advised," least of all by a woman, and he was known to harbor grudges. In 1951 he ordered Day to cease publication or remove the word "Catholic" from the name of her paper. She wrote him, saying respectfully that she had every right to publish it with the word "Catholic" in the title. Thunder and damnation might well have followed, but in fact the cardinal did nothing. She surmised that church officials had no stomach for members of her movement invading St. Patrick's Cathedral to hold prayer vigils begging the cardinal to relent (which they were quite ready to do) -- a spectacle that was bound to be reported by the press.

Fidel Castro’s takeover in Cuba in 1959 imposed a familiar dilemma on Dorothy Day, who went there to see firsthand what was happening. She deplored the aggressive atheism of Castro and his allies, yet applauded their efforts to improve the lives of ordinary people. And when Cardinal Spellman visited the troops in Vietnam in 1965 and praised the Vietnam war as a war for civilization, she avoided a direct confrontation, but listed all the war zones he had visited over the years, and wondered why there were American soldiers all over the world so far from our own shores. In spite of her criticism of casual extramarital sex and abortion, her pacifism won her the respect of the young radicals of the 1960s, all the more so when she hailed Ho Chi Minh as a man of vision and a patriot. Upon meeting her, Hippie leader Abbie Hoffman hailed her as "the original hippie."

The Cardinal Archbishop of New York was not used to being told that his actions were "misinformed" or "ill-advised," least of all by a woman, and he was known to harbor grudges. In 1951 he ordered Day to cease publication or remove the word "Catholic" from the name of her paper. She wrote him, saying respectfully that she had every right to publish it with the word "Catholic" in the title. Thunder and damnation might well have followed, but in fact the cardinal did nothing. She surmised that church officials had no stomach for members of her movement invading St. Patrick's Cathedral to hold prayer vigils begging the cardinal to relent (which they were quite ready to do) -- a spectacle that was bound to be reported by the press.

Fidel Castro’s takeover in Cuba in 1959 imposed a familiar dilemma on Dorothy Day, who went there to see firsthand what was happening. She deplored the aggressive atheism of Castro and his allies, yet applauded their efforts to improve the lives of ordinary people. And when Cardinal Spellman visited the troops in Vietnam in 1965 and praised the Vietnam war as a war for civilization, she avoided a direct confrontation, but listed all the war zones he had visited over the years, and wondered why there were American soldiers all over the world so far from our own shores. In spite of her criticism of casual extramarital sex and abortion, her pacifism won her the respect of the young radicals of the 1960s, all the more so when she hailed Ho Chi Minh as a man of vision and a patriot. Upon meeting her, Hippie leader Abbie Hoffman hailed her as "the original hippie."

|

| Her nemesis, but not her ruler. |

Cardinal Spellman's departing this earth for celestial pastures in 1967 may have simplified her life a bit, but she was still prone to picket lines and controversy. Honors as well as disparagement came to her in her later years, but for the Church she was always a hot potato, a firm believer admirable in many ways, but at the same time a rebellious troublemaker. Despite ill health, in the 1970s she visited India and met Mother Teresa, and with a group of peace activists visited the Soviet Union. In 1973, while picketing in support of Cesar Chavez's effort to organize farm laborers in California, she was arrested yet again and spent ten days in jail.

Day spent her last years in another beach bungalow on the South Shore of Staten Island, where she could again relax and breathe in the sea air that she loved. In 1980, at age 83, she died of a heart attack at Mary House, a Catholic Worker house of hospitality on East 3rd Street in Manhattan, with her daughter at her side. She was buried in the Cemetery of the Resurrection, near the South Shore of Staten Island. Her gravestone bears the words Deo Gratias (Thanks be to God): a Catholic to the end. Said Abbie Hoffman, she was the “closest thing to a saint I’ll ever see.”

Day spent her last years in another beach bungalow on the South Shore of Staten Island, where she could again relax and breathe in the sea air that she loved. In 1980, at age 83, she died of a heart attack at Mary House, a Catholic Worker house of hospitality on East 3rd Street in Manhattan, with her daughter at her side. She was buried in the Cemetery of the Resurrection, near the South Shore of Staten Island. Her gravestone bears the words Deo Gratias (Thanks be to God): a Catholic to the end. Said Abbie Hoffman, she was the “closest thing to a saint I’ll ever see.”

Nor was Abbie alone in his opinion. Her Staten Island bungalow has been bulldozed, but in 2000 Pope John Paul II granted the Archdiocese of New York's petition to have her designated a candidate for sainthood and, as such, “a Servant of God.” Some members of the Catholic Worker movement immediately objected, saying this violated her own values. But in 2012 the U.S. bishops endorsed her sainthood campaign unanimously, and in 2016 the Archdiocese of New York launched a canonical inquiry into her life and work; the hunt for miracles was on.

Today Day's organization has some 250 houses of hospitality and farms in the U.S. and abroad, and the Catholic Worker, now published seven times a year, still sells for a penny a copy. Cardinal Spellman lies buried in a crypt under the main altar of St. Patrick's Cathedral in the company of eminent deceased ecclesiastics, but to my knowledge, there is no movement to declare him a saint.

Source note: The information for this post comes from various online sources, including a Fresh Air interview by Dave Davies of Dorothy Day's granddaughter, Kate Hennessy, on March 23, 2017. This interview followed the publication of Hennessy's biography of Day, The World Will Be Saved by Beauty: An Intimate Portrait of My Grandmother (Scribner, 2017).

If you love the city (or hate it), this may be the book for you. An award winner, it sold well at BookCon 2017 and 2018.

Reviews

"If you want wonderful inside tales about New York, this is the book for you. Cliff Browder has a way with his writing that makes the city I lived in for 40 plus years come alive in a new and delightful way. A refreshing view on NYC that will not disappoint." Five-star Amazon customer review by Bill L.

"To read No Place for Normal: New York is to enter into Cliff Browder’s rich and engaging sixty years of adult life in New York. Yes, he delves back before his time – from the city’s origins to the 19th Century that Ms. Trollope and Mr. Dickens encounter to robber barons and slums that marked highs and lows of the earlier Twentieth Century. But Browder has lived such an engaged and curious life that he can’t help but cross paths with every layer and period of society. There is something Whitmanesque in his outlook." Five-star Amazon customer review by Michael P. Hartnett.

Available from Amazon and Barnes & Noble.

For readers who like historical fiction and a fast-moving story.

"A real yarn of a story about a lovable pickpocket who gets into trouble and has a great adventure. A must read." Five-star Amazon customer review by nicole w brown.

"This was a fun book. The main character seemed like a cross between Huck Finn and a Charles Dickens character. I would recommend this." Four-star LibraryThing review by stephvin.

Reviews

"At times amusing, gritty, heartfelt and a little sexy -- this would make a great summer read." Four-star Amazon customer review by BobW.

"Really more of a fantasy of a 19th century gay life than any kind of historical representation of the same." Three-star Goodreads review by Rachel.

Available from Amazon and Barnes & Noble.

4. Fascinating New Yorkers: Power Freaks, Mobsters, Liberated Women, Creators, Queers, and Crazies (Black Rose Writing, 2018).

Short biographical sketches of colorful people who lived or died in New York. A cardinal who led a double life, a serial killer, a baroness with a tomato-can bra, and a film star whose funeral caused an all-day riot.

"Unputdownable." Five-star review by Dipali Sen, retired librarian.

Today Day's organization has some 250 houses of hospitality and farms in the U.S. and abroad, and the Catholic Worker, now published seven times a year, still sells for a penny a copy. Cardinal Spellman lies buried in a crypt under the main altar of St. Patrick's Cathedral in the company of eminent deceased ecclesiastics, but to my knowledge, there is no movement to declare him a saint.

Source note: The information for this post comes from various online sources, including a Fresh Air interview by Dave Davies of Dorothy Day's granddaughter, Kate Hennessy, on March 23, 2017. This interview followed the publication of Hennessy's biography of Day, The World Will Be Saved by Beauty: An Intimate Portrait of My Grandmother (Scribner, 2017).

Coming soon: Maybe something on the honey bee and me -- another of my love affairs with nature.

BROWDERBOOKS

All books are available online as indicated, or from the author.

1. No Place for Normal: New York / Stories from the Most Exciting City in the World (Mill City Press, 2015). Winner of the Tenth Annual National Indie Excellence Award for Regional Non-Fiction; first place in the Travel category of the 2015-2016 Reader Views Literary Awards; and Honorable Mention in the Culture category of the Eric Hoffer Book Awards for 2016. All about anything and everything New York: alcoholics, abortionists, greenmarkets, Occupy Wall Street, the Gay Pride Parade, my mugging in Central Park, peyote visions, and an artist who made art of a blackened human toe. In her Reader Views review, Sheri Hoyte called it "a delightful treasure chest full of short stories about New York City."

If you love the city (or hate it), this may be the book for you. An award winner, it sold well at BookCon 2017 and 2018.

|

"If you want wonderful inside tales about New York, this is the book for you. Cliff Browder has a way with his writing that makes the city I lived in for 40 plus years come alive in a new and delightful way. A refreshing view on NYC that will not disappoint." Five-star Amazon customer review by Bill L.

"To read No Place for Normal: New York is to enter into Cliff Browder’s rich and engaging sixty years of adult life in New York. Yes, he delves back before his time – from the city’s origins to the 19th Century that Ms. Trollope and Mr. Dickens encounter to robber barons and slums that marked highs and lows of the earlier Twentieth Century. But Browder has lived such an engaged and curious life that he can’t help but cross paths with every layer and period of society. There is something Whitmanesque in his outlook." Five-star Amazon customer review by Michael P. Hartnett.

Available from Amazon and Barnes & Noble.

2. Bill Hope: His Story (Anaphora Literary Press, 2017), the second novel in the Metropolis series. New York City, 1870s: From his cell in the gloomy prison known as the Tombs, young Bill Hope spills out in a torrent of words the story of his career as a pickpocket and shoplifter; his brutal treatment at Sing Sing and escape from another prison in a coffin; his forays into brownstones and polite society; and his sojourn among the “loonies” in a madhouse, from which he emerges to face betrayal and death threats, and possible involvement in a murder. Driving him throughout is a fierce desire for better, a persistent and undying hope.

For readers who like historical fiction and a fast-moving story.

Reviews

"A real yarn of a story about a lovable pickpocket who gets into trouble and has a great adventure. A must read." Five-star Amazon customer review by nicole w brown.

"This was a fun book. The main character seemed like a cross between Huck Finn and a Charles Dickens character. I would recommend this." Four-star LibraryThing review by stephvin.

Available from Amazon and Barnes & Noble.

3. The Pleasuring of Men (Gival Press, 2011), the first novel in the Metropolis series, tells the story of a respectably raised young man who chooses to become a male prostitute in late 1860s New York and falls in love with his most difficult client.

What was the gay scene like in nineteenth-century New York? Gay romance, but no porn. Women have read it and reviewed it. (The cover illustration doesn't hurt.)

What was the gay scene like in nineteenth-century New York? Gay romance, but no porn. Women have read it and reviewed it. (The cover illustration doesn't hurt.)

Reviews

"At times amusing, gritty, heartfelt and a little sexy -- this would make a great summer read." Four-star Amazon customer review by BobW.

"Really more of a fantasy of a 19th century gay life than any kind of historical representation of the same." Three-star Goodreads review by Rachel.

"The detail Browder brings to this glimpse into history is only equaled by his writing of credible and interesting characters. Highly recommended." Five-star Goodreads review by Nan Hawthorne.

Available from Amazon and Barnes & Noble.

Short biographical sketches of colorful people who lived or died in New York. A cardinal who led a double life, a serial killer, a baroness with a tomato-can bra, and a film star whose funeral caused an all-day riot.

Reviews

"Fascinating New Yorkers by Clifford Browder was like sitting down with a dear friend and catching up on the latest gossip and stories. Written with a flair to keep the reader turning the pages, I couldn't stop reading it and thinking about the subjects of each New Yorker. I love NYC and this book just added to the list of reasons why, a must read for those who love NYC and the people who have lived there." Five-star NetGalley review by Patty Ramirez, librarian.

"Unputdownable." Five-star review by Dipali Sen, retired librarian.

"I felt like I was gossiping with a friend when reading this, as the author wrote about New Yorkers who are unique in one way or another. I am hoping for another book featuring more New Yorkers, as I couldn't put this down and read it in one sitting!" Five-star NetGalley review by Cristie Underwood.

© 2018 Clifford Browder

This comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

ReplyDelete