BROWDERBOOKS

This post is all about books, including mine.

TEN

REASONS WHY PRINT

BOOKS

OUTSELL E-BOOKS

In post #437 I listed the

five essentials I cannot do without:

· Bread

· Trees

· Books

· Sleep

· Hope.

I then promised an occasional

post on each, and proceeded to do Bread. So here is a post on Books.

It is an acknowledged fact today that print book sales are rising, while e-book sales are falling. How come? Here are ten reasons.

1.

A shiny new book

is a tactile experience. You touch it, feel its weight, hold it. You can even smell it. It is most definitely there, an experience you never really have with an e-book.

2.

You can flip back

and forth through a print book, leave a book mark in it.

3.

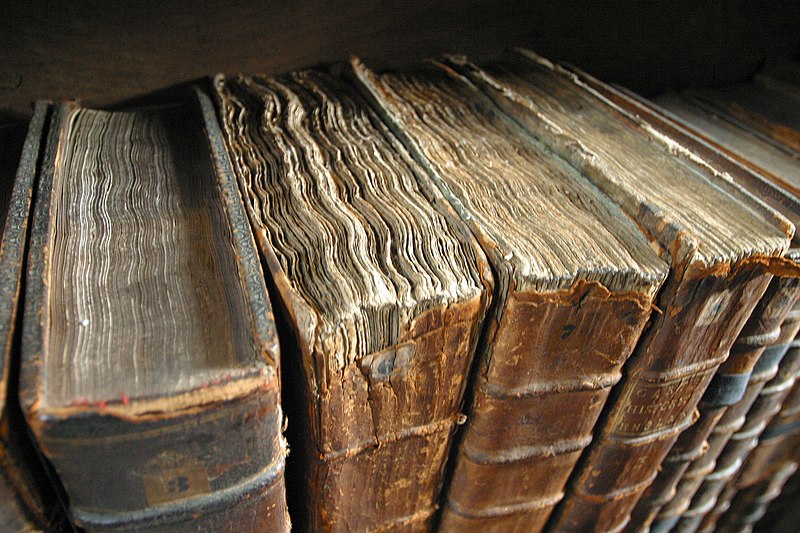

An old print book

shows its age and use, shows how important it has been to you. You can read your old underlinings and

scribbled marginal notes, and remember why the content mattered to you. The old books on my shelves, their split

spines mended with tape, have an aura all their own, even if bits of binding

are coming loose. They have shared a good

part of my life’s adventure over the years.

|

4.

A print book lets

you see how far you’ve come in reading, and how far you have to go. If the content is interesting but challenging,

marking progress can help you stay with it.

5.

Reading print

books causes less eye strain than reading digital books.

6.

An unread print

book on your desk or bookshelf can haunt you, entice you into reading it. Some 60% of downloaded e-books in the U.S.

are never read.

7.

Studies indicate

that print book readers absorb more information. Which probably explains why having a home

library is linked to higher academic achievement.

8.

Print book

readers are less likely to get distracted.

9.

Reading print

books helps you sleep better. (It has something to do

with the body’s level of melatonin, which induces sleep.)

10.

Print books don’t need batteries or a plug and an outlet. You can read them anywhere, as for instance on the beach.

|

| Credit: Radness.com.au |

As an author, I delight in both print-book and e-book sales; the main thing is that people are buying my books. But I grew up with print books, still have some of them from my early years, and value them highly. Think of curling up in an armchair on a cold and windy night, maybe with some fresh-made coffee and a snifter of Courvoisier V.S.O.P. brandy, and a favorite book. Or, minus the coffee and brandy, just with a book.

|

Or think of browsing through that vanishing phenomenon, a used bookstore, maybe with the owner and a napping cat, and finding fascinating old books that you didn’t know existed, or that you’ve been looking for for years.

|

| brewbooks |

Or how about a bookstore with shiny new books that tempt you with their bright covers and catchy titles. Or finding at home an old book you haven’t seen for years, maybe with an inscription from a friend that lets you relive a fragment of your past.

Print books have a long history that digital books lack. In the ancient Middle East clay tablets marked by an instrument called a calamus served as books. But there were problems. They were bulky, clunky things for storage, and you couldn't correct a mistake. I wouldn't have wanted to be the court scribe of any of the Assyrian kings, whose delight it was to castrate a captured enemy monarch before putting him to death.

Then, in Mediterranean societies (Egypt, Greece, Rome), books were papyrus scrolls on which people wrote by hand – in Roman times, often a whole team of educated slaves. Papyrus was made by processing a plant, the papyrus reed. Our word “paper" comes from “papyrus.” But here, too, there were problems. Papyrus scrolls, were crumbly things; unlike clay tablets, they didn't last.

Then, in Mediterranean societies (Egypt, Greece, Rome), books were papyrus scrolls on which people wrote by hand – in Roman times, often a whole team of educated slaves. Papyrus was made by processing a plant, the papyrus reed. Our word “paper" comes from “papyrus.” But here, too, there were problems. Papyrus scrolls, were crumbly things; unlike clay tablets, they didn't last.

|

| A 3rd-century BCE Greek papyrus manuscript. |

In the Middle Ages monks sat at desks printing by hand on

parchment, which was made by processing the skins of animals. (No animal rightsers back then.) Laborious work, but they did it lovingly, adding elaborate

illustrations, termed illuminations, that are highly valued works of art

today. And not a bad job, if the

Benedictine monastery at Mont-Saint-Michel in Normandy was typical. There, the only heated room in winter was the

scriptorium, where such work was done. But parchment was costly and therefore reserved for important works, usually religious.

I have seen clay tablets and papyrus only in museums, but parchment I see daily. Framed on my living room wall are two eighteenth-century parchments that I acquired in Paris long ago: two pages of Gregorian chant, with musical notes and the accompanying Latin text, which I have managed to translate. They dominate the room.

I have seen clay tablets and papyrus only in museums, but parchment I see daily. Framed on my living room wall are two eighteenth-century parchments that I acquired in Paris long ago: two pages of Gregorian chant, with musical notes and the accompanying Latin text, which I have managed to translate. They dominate the room.

|

| A Rheims gospel book, with illustrations. |

In the late Middle Ages paper, long known in China, where it was made from plant fibers combined with other substances, came to

Europe. It was there in Germany in the 1400s to make Gutenberg

and the printing press possible, and with them the advent of the printed book as we

know it today.

Books multiplied in numbers and in time became available to all, which had both good and bad consequences. The peak of book production at that time came in the late 1600s in the Dutch Republic, newly freed from Spanish rule and experiencing a Golden Age that we know chiefly from its paintings. Book production per capita there was ten times greater than in France or Spain, totaling an astonishing 300 million books. It was then that books became a part of daily human experience, and they remain so today. Democracy as we know it depends on a free press, and that means not just newspapers but books.

|

| Johannes Gutenberg. A drawing made after his death in 1468. |

Books multiplied in numbers and in time became available to all, which had both good and bad consequences. The peak of book production at that time came in the late 1600s in the Dutch Republic, newly freed from Spanish rule and experiencing a Golden Age that we know chiefly from its paintings. Book production per capita there was ten times greater than in France or Spain, totaling an astonishing 300 million books. It was then that books became a part of daily human experience, and they remain so today. Democracy as we know it depends on a free press, and that means not just newspapers but books.

In the nineteenth century improved technology made

the production of paper cheaper. This,

combined with better means of communication and transportation, made

possible a phenomenon still with us today: the bestseller. Examples:

· Victor Hugo’s Les

Misérables (1862), which in one form or another is still with us today. As a high school student, I read a selection

from it in a third-year French class.

· Alexandre Dumas’s The

Count of Monte Cristo (1844), which in a touring stage version here in the U.S. gave a steady income to Eugene O’Neill’s father, perhaps to the detriment of his theatrical

talent. (Over and over again, just this

one successful role.) I saw a movie

version long ago.

· Alexandre Dumas’s The

Three Musketeers (1844), which was also adapted for film. Two major publications in one year! Dumas père

sure could turn them out. I’ve seen

it as a film, and as a tongue-in-cheek stage production here in New York by the

Comédie Française.

· Our own Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852), whose

success worldwide astonished both her and her publisher. The reason: it dealt with a subject – slavery

– that the country could no longer dodge.

An apocryphal story circulated in later years, telling how President

Abraham Lincoln, upon meeting Mrs. Stowe at a White House reception during the

Civil War, said, “Ah, so you’re the little lady who started this big war!” An exaggeration, if he ever said it (he

probably didn’t), but with a touch of truth.

A melodramatic stage version circulated for years, and even made its

appearance, as an improvised Siamese version, in the 1951 Broadway musical The King and I. I’ve tried twice to read the novel,

couldn’t. It’s often referred to as one

of the bad good books, or good bad books, esteemed for its historical impact,

but not its literary merit.

And of course there were many more bestsellers, some totally

forgotten today (works of Sir Walter Scott, for instance), and some remembered,

such as works of Dickens, Flaubert, Mark Twain, Dostoevsky, and Tolstoy. But who is generally considered the best nineteenth-century

bestseller of all, the one who sold the most books by far? Take a guess.

You’ll find the answer under Answer at the end of this post.

And who is the top bestselling author of all time? According to one Internet source, Barbara

Cartland, with one billion copies sold.

Have you ever heard of her? I

haven’t. An author of romance novels,

she wrote 723 books in all. But another

source says Agatha Christie, with two billion sold. Agatha I have heard of, though I haven't stuck my nose in any of her mysteries. Like it or not, the world needs mysteries and it

needs romance.

|

| Tom Murphy VII |

And now, three more points

about books. Print books, of course, and

especially mine.

1.

PRINT BOOKS MAKE

DANDY GIFTS.

It’s the holiday season, and

as an author (and therefore vastly self-interested), I urge everyone to give a

friend or family member a book. My

books, of course, especially the ones I have too many of in my apartment. These are historical fiction, New York City.

|

The story of a lovable street kid turned pickpocket in nineteenth-century New York. Of all my fictional characters, he is by far my favorite.

"A must read." Five-star Amazon customer review by nicole w brown.

"I can't recommend this book enough." Five-star Barnes & Noble customer review by ladynicolai.

|

"The novel is worth reading and I highly recommend it." Midwest Book Review by Nicole Williamson, retired librarian.

'Thoroughly enjoyed this historical book! I recommend to read! Facts accurate!" Five-star Goodreads review by LisaMarie.

|

"Amazing book and the story line kept me reading on and on." Five-star Goodreads review by Kathy.

"Engaging and provocative." Barnes & Noble editorial review by Sean Moran.

"Absolutely delightful. Five Bees." Gerry Burnie's Reviews.

All books available from Amazon and Barnes & Noble, but these three preferably from the author at $20.00 each plus postage. Contact me by e-email at cliffbrowder@verizon.net. (If you're in the city, we can arrange to meet; that way, no postage.) And if you buy two, half price for the second.

And now, after that grossly commercial and outrageously self-interested spiel, let's finish the list of three more points about books:

2. MY

BOOKS ARE GLUTEN-FREE.

3. MY

BOOKS ARE MADE

IN AMERICA.

But if you don’t buy my

books, buy someone else’s. Books look

great when gift-wrapped; they create expectation and are fun to open.

Also: print books last. Especially hardcovers. But even paperbacks last far longer than an e-book, which has no presence off a computer. So Merry Christmas, Happy Hanukkah, Joyous Kwanzaa, and all the rest. (Here in New York, we do them all.) Whether giving or receiving, may your holiday be blessed with books.

|

| Donald Trung Quoc Don |

Also: print books last. Especially hardcovers. But even paperbacks last far longer than an e-book, which has no presence off a computer. So Merry Christmas, Happy Hanukkah, Joyous Kwanzaa, and all the rest. (Here in New York, we do them all.) Whether giving or receiving, may your holiday be blessed with books.

Answer: Harriet Beecher Stowe.

Uncle Tom’s Cabin was the no. 1 worldwide bestseller. Not a literary masterpiece, and neither a

romance novel nor a mystery. But it came at the right time and said what most

needed to be said.

So much for books for now. A fascinating subject.

So much for books for now. A fascinating subject.

Coming soon: “Five Wonders I Will Never See.” And after that, probably “The King of Harlem.”

© Clifford Browder 2019

No comments:

Post a Comment