Big wide-mouthed apothecary jars of

another time, with glass stoppers and bold labels reading

CARDAMOM

CAMPHOR

BELLADONNA

ASAFOETIDA

BENZOIN

A host of smaller brown bottles

with similar labels on a table, perhaps a medicine chest, that has seen better

days.

An outiszed mortar and pestle, and

a number of glass tubes and receptacles probably used to distill

medications. Metal canisters labeled ALUM and, intriguingly,

CHOICE

BOTANIC DRUGS

PRESSED

|

| Apothecary jars |

In a protective glass case, antique

scales. What looks to be an old radio,

and another large object I can’t identify.

And, as the centerpiece of the display, a huge prescription book, the

edges of its pages not yellow but brown with age, open to scores of

prescriptions scribbled in an indecipherable hand, but whose year, if you

squint and look closely, can be made out: 1917.

And in bold print at the top of each prescription, FRANK AVIGNONE & CO.

Such is the current window display at

Grove Drugs at 302 West 12th Street, but a couple of blocks from my

apartment, one of the few independent pharmacies left in the West Village, where

chain stores dominate. Grove’s window

displays are always of interest, but this one fascinated me at first glance,

since it took me back to the apothecary shops of the nineteenth and early

twentieth century. When I asked inside

about the source of these relics from the past, I was told that they had

belonged to a pharmacy at Bleecker Street and Sixth Avenue, now closed, that

had gone back a century or more.

(Note:

The word “apothecary” can designate either the shop or the medicine

compounder working in the shop. To avoid

confusion, I will use “apothecary shop” for the shop.)

I soon identified the pharmacy in question

as Avignone Chemists, formerly Avignone Pharmacy, which had been at Bleecker

and Sixth Avenue since 1929. But the

pharmacy traces its origins back to 1832, when its antecedent was founded as

Stock Pharmacy at 59 MacDougal Street, at the corner of Houston, one of the

oldest apothecary shops in the United States.

In 1898 Stock Pharmacy was bought by Frank Avignone, an Italian

immigrant, who changed the name to Avignone Pharmacy. When the building was demolished in 1929 for

the widening of Houston Street, Frank and Horatio Avignone built a two-story brick

structure at 281 Sixth Avenue/226 Bleecker Street and moved their pharmacy

in. Frank Avignone’s son Carlo took over

the business in 1956 and in 1974 sold it to the Grassi family, who were joined

by Abe Lerner in 1991.

(A parenthesis to the above: Wikipedia

calls Avignone the oldest apothecary shop in the U.S., but that honor is also

claimed by another Village independent, C.O. Bigelow’s, at 414 Sixth Avenue,

just above West 8th Street, which dates its founding to 1838. This assertion relies on affiliating

Bigelow’s with its predecessor, the Village Apothecary Shop, which was indeed

established at a nearby location in 1838 by Dr. Galen Hunter. Clarence Otis Bigelow, an employee of Dr.

Hunter’s successor, bought the shop from his boss in 1880, renamed it after himself,

then built the present building and moved into it in 1902. Which of these claims, if either, is valid, I

leave to the viewer. I will only observe

that an apothecary shop opened in Williamsburg, Virginia, in 1759, a slightly

earlier date than either date cited by these pharmacies.)

When Abe Lerner and his co-owners

renovated the building in 2007, they changed the name to Avignone

Chemists. The blond wood-frame exterior

and double-door entrance, topped by a striped awning and an illuminated green

cross indicating a pharmacy, gave it a welcoming warmth such as few chain pharmacies can boast. In the front window and on display inside

were the very items of which I saw a selection in Grove Drug’s window: old

apothecary jars, mortars and pestles, old clocks and radios and cameras, and

several massive prescription books, all of which had been discovered in the

basement during the 2007 renovation.

The end for Avignone came earlier this

year, when the building was sold and the new owner, Force Capital Management, a

New York-based hedge fund founded in 2002, tripled the pharmacy’s rent to

$60,000, which Abe Lerner could not pay.

Lerner, now 62, choked up at the thought of closing on April 30. “I’ve spent half my life here,” he told an

interviewer. “I’ve known many of these

people for thirty years; I’ve seen a lot of kids grow up. A lot of these people have become friends --

they’re not just customers, they’re friends.”

The whole neighborhood mourns the pharmacy’s loss as well, for it had

become a neighborhood hangout, a place to come and chat with friends. Yet another example of how soaring commercial

rents, which are not controlled, can gut a neighborhood, driving out

mom-and-pop stores that have been in the neighborhood for years.

I walked by the old pharmacy at the corner

of Sixth Avenue and Bleecker Street a couple of months after the closing, and

there it was, a two-story building dwarfed by its neighbors, with “AVIGNONE

CHEMISTS” above the striped awning, and on the awning “est. 1932,” which might

be considered a bit of a stretch, since that date applies to a different

pharmacy with a different name at a different address. The double door is padlocked, and in the

window is a big sign, RETAIL AVAILABLE, indicating that no new tenant has as

yet been found. And if one enters

Winston Churchill Square, the small fenced park adjoining, high up on the

building’s brick wall you can still see a faded sign probably dating from the

1950s:

AVIGNONE PHARMACY

PRESCRIPTIONS

And what about Grove Drugs, whose display

set me off on this investigation? It’s a

small pharmacy whom an online Yelp reviewer describes as “a fine, friendly,

old-fashioned neighborhood pharmacy.”

True enough. Like Avignone

Chemists, Grove relishes its status as an independent pharmacy competing with the

chain stores: David against Goliath, the little guy against the multiple massive

presence of CVS Pharmacy, Duane Reade, and Rite-Aid. Being small, it can offer only the basic

basics, as compared with the Rite-Aid on Hudson Street, which has five times

the floor space and offers a bewildering variety of products, including

children’s toys, seasonal greeting cards, and junk-food snacks.

|

| Not exactly a friendly neighborhood pharmacy. Jim.henderson |

Rite-Aid entices me with a so-called

Wellness Card offering a 20% discount – not to be sniffed at -- on the first

Wednesday of every month, but I can wander its many aisles without ever encountering

an employee. If I go to Grove, at the

counter in back there’s always someone to point me to whatever I need. Also, I like the plain-Jane simplicity of

“Grove Drugs,” as opposed to “Village Apothecary,” another West Village

independent, and yes, even “Avignone Chemists,” which to my mind hint of

pretension. And there’s something

charmingly quaint about Grove’s closing on Sunday and holidays (“Please

anticipate your needs”), and at 7:30 p.m. on weekdays, while the chain stores

are open 24/7. As for its seasonal window displays – an

animated wintry panorama with a miniature toy factory, carolers, and skaters at

Christmas, bunnies at Easter, and skulls and bats and huge spiders and their

webs at Halloween – they are the most entertaining in the entire West Village.

And why does the pharmacy at 202 West 12th

Street bear the name “Grove Drugs”?

Because for many years the owner, John Duffy, operated another West

Village independent, Grove Pharmacy, at 261 Seventh Avenue, on the corner of

Grove Street, until forced out by his landlord in 2006. And why did the artifacts of the Avignone

Chemists come to Grove Drugs? Because

John Duffy was part owner of Avignone as well.

So Grove Drugs must be his last stand against greedy landlords and

invasive chain stores. I wish him well.

But I’m not quite done with the

fascinating relics in Grove’s window, for to fully grasp their significance you

have to understand the role of the old-time

apothecary, a profession dating back to antiquity and differing from that of

today’s pharmacist. Pharmacies today are

well stocked with over-the-counter products mass-produced by pharmaceutical

companies; they come in standardized dosages formulated to meet the needs of

the average user. But throughout the

eighteenth and nineteenth centuries the apothecary, the predecessor of today’s

pharmacist, created medications individually for each customer, who received a

product that was, so to speak, tailor-made.

In theory, the apothecary had some knowledge of chemistry, but at first there

was little regulation.

|

| A 17th-century German apothecary. Welcome Library |

The objects on display in Grove’s window hearken

back to this early period when the apothecary made compounds from ingredients

like those in the bottles and jars displayed, grinding them to a powder with a

mortar and pestle, weighing them with scales to get the right measure, or

distilling them with the glass paraphernalia seen in the window to make a

tincture, lotion, volatile oil, or perfume.

The one thing typical of the old apothecary shops that the display can’t

reproduce was the aroma, a strange mix of spices, perfumes, camphor, castor

oil, and other soothing or astringent remedies.

Mercifully absent as well is a jar with live leeches, since by the late

nineteenth century the time-honored practice of bloodletting, which probably

killed more patients than it benefited, had been discontinued.

The apothecary’s remedies were derived

sometimes from folk medicine and sometimes from published compendiums. Chalk was used for heartburn, calamine for

skin irritations, spearmint for stomachache, rose petals steeped in vinegar for

headaches, and cinchona bark for fevers. Often serving as a physician, the apothecary

applied garlic poultices to sores and wounds and rheumatic limbs. Laudanum, or opium tincture, was employed

freely, with little regard to its addictiveness, to treat ulcers, bruises, and

inflamed joints, and was taken internally to alleviate pain. Little wonder that well-bred ladies became

addicted, like Eugene O’Neill’s mother, as memorably portrayed in his play A Long Day’s Journey into Night. But if some of these remedies seem

fanciful or naïve or even dangerous, others are known to work even today, as

for example witch hazel for hemorrhoids.

But medicines weren’t the only products of

an apothecary shop. Rose petals,

jasmine, and gardenias might be distilled to create perfumes, and

lavender, honey, and beeswax were compounded to create face creams to enhance the milk-white complexion desired

by ladies, in a time when the sun tan so prized today characterized a market

woman or farmer’s wife, lower-caste females who had to work outdoors for a

living. (The prime defense against the sun

was, of course, the parasol, without which no lady ventured outdoors.) A fragrant pomade for the hair was made of

soft beef fat, essence of violets, jasmine, and oil of bergamot, and cosmetic

gloves rubbed on the inside with spermaceti, balsam of Peru, and oil of nutmeg

and cassia were worn by ladies in bed at night, to soften and bleach the hands,

and to prevent chapped hands and chilblains.

But the apothecary’s products were not

without risks. Face powders might

contain arsenic; belladonna, a known poison, was used to widen the pupils of

the eyes; and bleaching agents included ammonia, quicksilver, spirits of turpentine, and tar. All of which suggests a less than

comprehensive grasp of basic chemistry. And

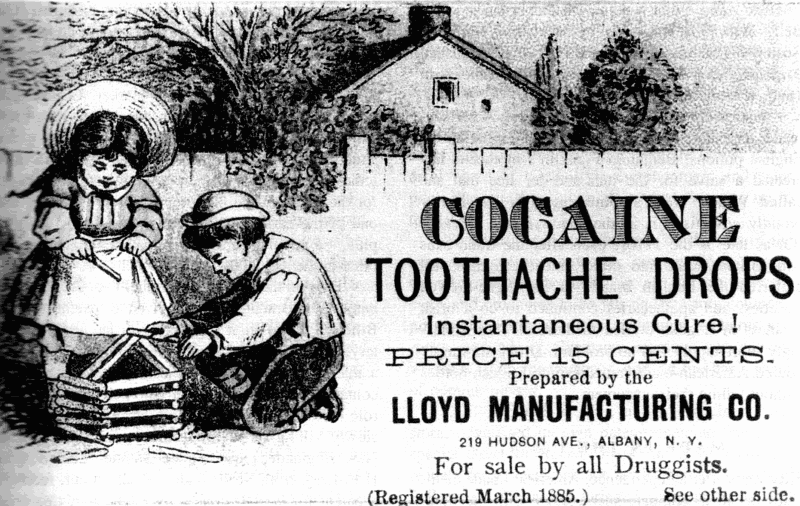

in the flavored syrups and sodas devised to mask the unpleasant medicinal taste

of prescriptions, two common ingredients were cocaine and alcohol, which must

have induced in the patients an unwonted buoyancy of spirits.

|

| Marketed especially for children, no less. |

Also available in an apothecary shop were

cooking spices, candles, soap, salad oil, toothbrushes, combs, cigars, and tobacco,

so that it in some ways approximated the general store of the time. And in the eighteenth century American

apothecaries also made house calls, trained apprentices, performed surgery, and

acted as male midwives.

Belladonna, which appears in the Grove Drugs

window display, merits a mention of its own.

The name means “beautiful lady” in Italian, for the juice of its berry

was used by Italian women in the Renaissance to dilate the pupils of their eyes

so as to appear more seductive. A

sinister and risky beauty resulted, for this small shrub that grows in many

parts of the world, including North America, produces leaves and berries that

are extremely toxic, as indicated by its other common name, “deadly

nightshade.” It has long been known as a

medicine, poison, and cosmetic.

Nineteenth-century medicine used it to alleviate pain, relax the

muscles, and treat inflammation, and it is still in use today as a sedative to

stop bronchial spasms, and also to treat Parkinson’s, rheumatism, and other ailments.

Belladonna, which appears in the Grove Drugs

window display, merits a mention of its own.

The name means “beautiful lady” in Italian, for the juice of its berry

was used by Italian women in the Renaissance to dilate the pupils of their eyes

so as to appear more seductive. A

sinister and risky beauty resulted, for this small shrub that grows in many

parts of the world, including North America, produces leaves and berries that

are extremely toxic, as indicated by its other common name, “deadly

nightshade.” It has long been known as a

medicine, poison, and cosmetic.

Nineteenth-century medicine used it to alleviate pain, relax the

muscles, and treat inflammation, and it is still in use today as a sedative to

stop bronchial spasms, and also to treat Parkinson’s, rheumatism, and other ailments.  |

| A witches' sabbath, Goya version. Satan often appeared as a goat. |

Belladonna figures often in history and

legend. It is said that Livia, the wife

of the Roman emperor Augustus, used it

to kill her husband. And in folklore,

witches used a mixture of belladonna, opium, and other poisons to help them fly

to conclaves of witches called sabbaths, where participants did naughty things,

danced wildly, and kissed the devil’s behind.

The shiny black berries have been called “murderer’s berries,”

“sorcerer’s berries,” and “devil’s berries.”

All in all, not a plant to mess with,

although a staple in most apothecary shops of former times. If you think you’ve never gone near it, think

again, for if you’ve ever had your eyes dilated, belladonna is in the eye

drops. And I’ll admit that the name

intrigues me: belladonna, the beautiful lady who poisons. Which brings us back to the Empress Livia; maybe

she did do the old boy in.

Gradually, the professions of apothecary

and pharmacist -- never quite distinct –

became more organized, then regulated. In the nineteenth century patent medicines (which

were not patented) became big

business, thanks to advertising, but their mislabeling of ingredients and extravagant claims inspired

a growing desire for regulation that finally resulted in the Pure Food and Drug

Act of 1906. This and subsequent

legislation probably benefited apothecaries, since mass-produced patent

medicines competed with their products.

|

| An FDA exhibit of dangerous products that the 1906 act didn't cover, used to campaign for stricter legislation, which was enacted in 1938. |

As late as the 1930s and 1940s,

apothecaries still compounded some 60% of all U.S. medications. In the years following World War II, however,

the growth of commercial drug manufacturers signaled the coming decline of the

medicine-compounding apothecary, just as the use of the mortar and pestle diminished

to the point of becoming a quaint and charming symbol of a bygone era. In 1951 new federal legislation introduced

doctor-only legal status for most medicines, and from then on the modern

pharmacist prevailed, dispensing pre-manufactured drugs.

By the 1980s large chain drugstores had

come to dominate the pharmaceutical sales market, rendering the survival of the

independent neighborhood pharmacy precarious.

Yet some of them do survive, as we have seen, and when one closes, the

whole neighborhood mourns. But in a

final twist, the word “apothecary,” meaning a place of business rather than a

medicine compounder, has become “hip” and “in,” appearing in names of

businesses having nothing to do with medicines.

It expresses a nostalgia for experience free from technology and

characterized by creativity and a personal touch, a longing for Old World

tradition and gentility. And as one

observer has commented, “apothecary” is fun to say.

A note on poisonous plants: Though it grows in North America, I’ve never

seen belladonna, nor is it listed in U.S. field guides. But other poisonous plants are common, and

I’ve seen them in the field. Poison ivy

is ubiquitous but too familiar to dwell on.

Stinging nettle (Urtica dioica)

does indeed sting, as I know from experience, and cursed buttercup (Ranunculus sceleratus), which I’ve seen

growing in shallow swamp water in Van Cortland Park, causes blisters if

touched; yet neither is described as poisonous.

Poison hemlock (Conium maculatum),

an umbrella-like plant with terminal clusters of tiny white flowers and finely

divided fernlike leaves, grows in one shady spot in Van Cortland Park and lives

up to its name, since its juices are highly toxic; in ancient Athens it was the

means for putting Socrates to death.

|

| Mick Talbot |

But the real surprise for me, in

researching poisonous plants, was to learn that jimsonweed (Datura stramonium), which I’ve seen

growing in dry soil in Pelham Bay Park in the summer, is both hallucinogenic

and poisonous. I should have known, for

it’s in the nightshade family, which includes belladonna. (And the potato and tomato, but that’s

another matter.) An erect, foul-smelling

plant with coarse-toothed leaves and big, trumpet-like flowers three to five

inches long, it attracts attention because of its large, pale violet flowers,

but there’s something about it that is brazen and coarse. The common name is a contraction of

“Jamestown weed,” for it was first described in America in 1676 in Jamestown,

Virginia. It has been used in folk

medicine as an analgesic, and in sacred ceremonies among Native American tribes

as a hallucinogen. But both the

medicinal and hallucinogenic properties are fatally toxic if used in slightly

higher amounts than the medicinal dosage, and many a would-be visionary and

adventurous thrill-seeker has ended up in the hospital, if not in a

coffin.

|

| H. Zell |

So here am I, reveling in the exotic charms

of belladonna, when right close to home, viewed every summer in a city park, is

a native species every bit as dangerous, and fascinating, as the beautiful eye-dilating

lady of the Renaissance. But no, I’m not

even remotely tempted to taste of the hallucinatory joys of jimsonweed, whose

other names include devil’s snare, devil’s trumpet, and hell’s bells. But it does make a hike in Pelham Bay Park

more interesting.

Coming soon: West Village Wonders and Horrors. Including a civilized parlor and the most talked-about monstrosity in the Village.

© 2015 Clifford Browder

No comments:

Post a Comment